On the trial of Forrest Fenn’s hidden treasure

From 2017: Thousands have dissected Fenn’s clue poem and searched for his hidden chest—and some have died trying. Allen Abel joins the hunt in New Mexico.

Rosy Verdile camped in forests and deserts for four years, seeking spiritual wellness in the public lands of Northern New Mexico. Verdile has seen increased traffic in the lands she calls home, watching “more worldly men in more worldy vehcles” seeking out the treasure. She understands their search, and likens it to her own.

Share

There is smoke in the valley at daybreak, and the smell of coal fire pinches the nostrils as the screen door of the old café claps shut. Above us is a sky as clear as gemstones. This chill will change to shimmering heat by lunchtime. The search begins.

Below the little village is a healthy, happy river called the Rio Chama, surging its way from the Colorado snow slopes, down through the piñon and juniper and yellow-red canyons of New Mexico, keeping its immemorial rendezvous with the mighty Rio Grande, divider of nations. And somewhere along the Chama’s banks—maybe—is a small chest whose contents are said to include, as in the words of Edgar Allan Poe in The Gold-Bug:

“A treasure of incalculable value . . . gold of antique date and of great variety . . . diamonds—some of them exceedingly large and fine—a hundred and ten in all, and not one of them small; eighteen rubies of remarkable brilliancy; three hundred and ten emeralds, all very beautiful; and twenty-one sapphires, with an opal.”

From the driver’s seat, “we’re almost out of gas” shatters that beautiful dream.

MORE FROM ALLEN ABEL: An epic quest to find the soul of a country

Two treasure-hunters in a sturdy RAV4 retreat from the riverbank to fill the tank at a town also named Chama, from which a steam-powered tourist train chugs northward every morning, pelting the perfect air with the whistle and puff of an earlier century. Our quest, as well, is ancient—to travel and trek across the American West with riches as the lure, mystery as the temptress, poetry as the scout, death as the trickster, and the majesty of the land itself as the prize.

For the past six years, thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—of starry-eyed seekers from all across this continent have made the same journey, scrabbling down canyons and wading through streams from Santa Fe to Saskatchewan in search of an old man’s strange and irresistible bequest: a bronze chest heaped with jewels, nuggets, trinkets and Indigenous artifacts both valuable and invaluable.

No one has credibly reported that he or she has found it. At least three men have perished on the trail. Many people, too cynical or too jealous or too lazy to even look, have labelled the entire enterprise a fatal hoax on a gullible, greedy world. In June, the chief of the New Mexico State Police urged that the chase be called off after the body of a Colorado pastor was found along the Rio Grande.

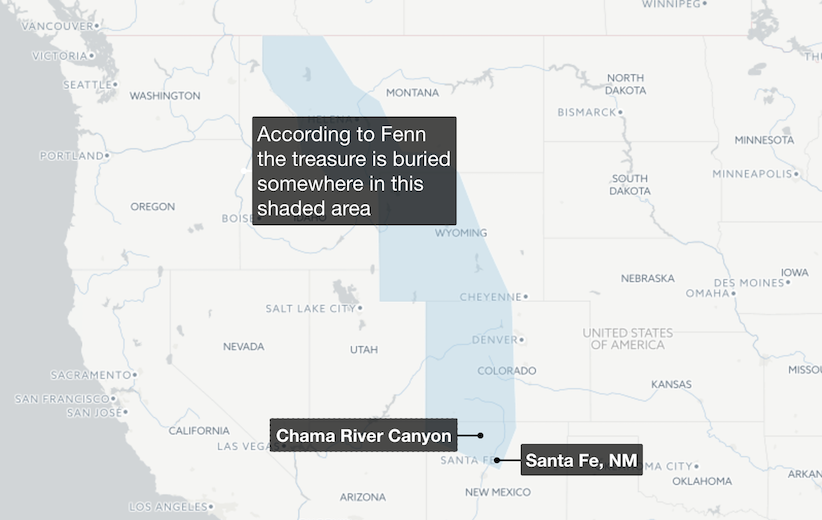

Only one man knows where this deadly treasure waits, or if it exists at all. He has written a poem encrypting nine clues that, he claims, even a child could follow to the hiding place. He has given some, but only a few, additional hints to the cache’s location over the past half-decade. (It’s not in Canada, not in a graveyard, not in a mine, not in a cave, not underwater, not in Utah, not in Idaho, not south of Santa Fe, not lower than 5,000 feet above sea level, not higher than 10,200 feet, not near a dam, and not under an outhouse.)

This leaves only the mountains, meadows, and plateaus of Colorado, Wyoming, Montana and northern New Mexico to be scoured in search of a box that is the size of a big-city telephone book.

The man has confessed that his primal intention, later retracted, was to kill his cancer-ridden self while cradling the chest, so that his bleached and clean-picked bones might be among the jewels. His autobiography, sealed in an olive jar, would be part of the hoard. So much for dead men telling no tales.

He beat the cancer and now accepts that he may die of natural causes long before the chest is discovered. Of this he says, “I would like to think that if it is ever found, I will know about it. If my treasure chest is not found for 500 years I will be just as happy as if it were found tomorrow.”

***

Here is the poem that leads to the trove, as authored by a man named Forrest Fenn, a Vietnam-era military pilot, Santa Fe art and antiquities dealer and collector, and multi-millionaire who turned 87 on Aug. 22 (2017):

As I have gone alone in there

And with my treasures bold,

I can keep my secret where,

And hint of riches new and old.

Begin it where warm waters halt

And take it in the canyon down,

Not far, but too far to walk.

Put in below the home of Brown.

From there it’s no place for the meek,

The end is ever drawing nigh;

There’ll be no paddle up your creek,

Just heavy loads and water high.

If you’ve been wise and found the blaze,

Look quickly down, your quest to cease,

But tarry scant with marvel gaze,

Just take the chest and go in peace.

So why is it that I must go

And leave my trove for all to seek?

The answers I already know,

I’ve done it tired, and now I’m weak.

So hear me all and listen good,

Your effort will be worth the cold.

If you are brave and in the wood

I give you title to the gold.

“I designed the hunt to be difficult, but certainly not impossible,” Fenn insists. “Most searchers don’t put enough emphasis on the first clue, and without it their effort is futile.

“The poem is written in plain English words that mean exactly what they say. No need to figure pounds per square inch, head pressures, acre feet, square roots, or where true north is, to find the solution.”

Fenn claims that 300,000 people either have gone searching for the box, or have emailed him to announce their intention to do so. That none of them has found it is a reflection on their own failures to interpret the clues in their correct order, he insists, and not on his skill as a poet, or the lack of same.

Why is the Brown in “home of Brown” capitalized, but not the M in meek, the seekers wonder. (There is a Meek’s Ranch on the west bank of the Rio Chama.) Does “Brown” refer to brown trout—Fenn is an avid fly fisherman—or to a person by that name? Are the “warm waters” the issue of hot springs or geysers, or merely less cold than a rushing river like the Chama or the Rio Grande, or the Madison, up in Yellowstone National Park, where Fenn summered as a boy? Does “put in” refer to a boat or to one’s own person?

How far, exactly, is “too far to walk?”

“Don’t overcook my poem,” Forrest Fenn decrees.

***

Rosy Verdile and her dog Petey are sitting on cushions on the hood of a gold-coloured Jeep at the head of a winding, rocky, one-lane road, as if heralding the pathway to the treasure. This mule-path follows the Rio Chama for 25 km and ends at the Roman Catholic Monastery of Christ in the Desert.

Petey trots off to examine a dead cow whose desiccated remains mimic what would have been the fate of Forrest Fenn, had he followed through on his original intention to take his own life beside his fantastical coffer.

We are hardly the first to muse that the canyon of the Chama, which is fed by several warmer rivulets and hot springs only a couple of hours from Santa Fe, may be Forrest Fenn’s hiding place, and that Christ in the Desert itself may be “the home of Brown,” since it is built of warm, tan adobe. Fenn is a Baptist, not a Catholic, but he did say that he was able to deposit his cache at the age of 79 or 80 in two easy walks from a parking lot, and on this road there are areas for kayak put-ins and take-outs and for the monks’ sanctuary as well.

“If the search was from Santa Fe to the Colorado state line, this would be a possibility,” Rosy Verdile says, semi-helpfully. “But if it’s Santa Fe to the Canadian border, it doesn’t have the feel.”

More than 20 years ago, Verdile abandoned a successful career as a painter and sculptor in Boston and ended up in the Chama valley, seeking inner peace, living in a tent. This evolved into a role as a lay helper at Christ in the Desert. “Recently,” she says, “we started seeing Geiger counters, picks and shovels, worldly people in worldly vehicles, willfully disregarding the ‘Private’ signs where the road ends at the monastery. They’re adamant. They want back there.”

These were treasure hunters, thirsting for the blaze, the trove, the cold, the wood. And now so are we.

A few minutes away is Ghost Ranch, made famous by Georgia O’Keeffe. Across the river is a piney height, topped by a forest-fire lookout tower, named Dead Man’s Peak. And a few steps from the gravel road itself is a crossing of the Chama named—we don’t know why—Skull Bridge.

Ghost Ranch. Skull Bridge. Dead Man’s Peak.

As I have gone alone in there . . .

A sick man stage-managing his own extinction could choose no fitter place. So we clamber down to the Rio Chama, which runs swift and cold and uncaring here, beneath a dazzling sky. We poke around and under the bridge, along the bank, in the rocks, looking for a brown box on a brown ledge in a brown canyon, or under a bush, or wedged in a tree.

Now a pickup truck comes crunching down the road to the monastery as we return from the fruitless search. The driver is a man named Lorenzo Martinez, who made and tends the mellow, rounded walls of Christ in the Desert. He has been looking, too.

“If I find it,” says Martinez, who is known locally as “the mud man,” “the first thing I would do is put in an automatic irrigation system on my land, so I could just push a button inside my house and turn the water on. And then I would grow marijuana.”

Martinez says that he is certain that he saw Forrest Fenn hide his treasure along the Chama road about six years ago. “An old guy with a raggedy-ass truck,” the mud man remembers. “He could hardly walk. I gave him a ride to the highway.”

***

Forrest Fenn lives behind a sliding blue gate on a sizable spread of brush, sand, bamboo, and gurgling little rivulets on the veritable Old Santa Fe Trail, whose wagon-ruts still are visible in his rear acreage.

His house itself is a one-man Louvre of Egyptian shawabtis, calfskin moccasins, Hopi kachinas, assorted liquor bottles branded FENN, a 17th-century Spanish chest filled with modern-day Sacajawea and Martin Van Buren “gold” dollars, and Mark Twain’s proof copy of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court annotated in the author’s hand, not to mention myriad daggers, pots, arrowheads, human and animal bones, Sitting Bull’s peace pipe and the 40-year-old passport Fenn needs to have reissued before he can renew his driver’s licence.

Most articles, blogs and broadcasts—and there have been thousands—describe Fenn as “eccentric.” House-proud, crafty, accumulative, literate, self-satisfied, sneaky, curious, pacifist yet Trump-loving, self-educated, playful and almost deaf, he is. But he is no oddball, no babbler, unless, of course, this all turns out to be a joke.

Fenn sits with a visitor for three hours of enchanting conversation that touches everything from his war experiences—he was shot down over Laos and retrieved the next day—to Donald Trump (“he hasn’t done anything to make me angry yet”) to the 1955 New York Yankees, who autographed a baseball that he ranks among his second-tier possessions. (Mickey Mantle signed thousands of balls, but Sitting Bull left only one pipe.)

Fenn says that he spent $8,000 in legal fees to determine what would happen to someone who stubbed his or her toe on a million-dollar carton of treasure inside a National Park. (The finder would have to deposit it with the park superintendent until the person who “lost” it released the box.)

He says that he received an email from a man who reported that he hadn’t spoken to his own brother for 17 years, but they went to search for the treasure together and now they are close again. He says that the whole purpose of his endeavour is “to get people off the couch, off the video games.”

He says that nobody—not even his wife or their two daughters—has been told where the chest can be found. He shows no favourable disposition toward the most inveterate searchers, some of whom have made more than 100 forays where warm waters halt below the home of Brown and got it wrong every time. He says, “If I was going to tell anybody where it is, I’d tell my grandson.”

He says that “it is a terrible tragedy that lives were lost while searching for my treasure. It is something I did not anticipate, and if I had, the treasure would never have been hidden. I was shocked when someone told me that an average of nine lives are lost each year at the Grand Canyon. There is some kind of risk in every participation.”

“Is there anything that would make you go get it?” Fenn is asked in his own still study, with all its handicrafts and manuscripts fashioned by and for the dead.

“If North Korea threatens to nuke New York City unless I go get it, I’ll go get it,” he answers.

Then: “What makes you think I can go get it?”

“Someone who’s greedy enough to get that much gold is too greedy to give it away,” philosophizes a man named Bill in the tiny coffee shack he runs on San Francisco Street in downtown Santa Fe.

This is a common jibe in the artsiest and most too-precious little city in the 50 states. “I think it’s just a joke, I don’t think it exists, it’s just a big ego thing for Forrest,” says a woman at a shop that sells new and antique pottery at prices of $200,000 and down.

“Bill at the coffee shack says you’re too greedy to give up that much gold,” one reports to Forrest Fenn.

“Bill Gates is the wealthiest man in the world, but I have never seen that word applied to him,” he replies. “If accumulating is greedy then all museums are guilty. It’s the thrill of the chase in many cases, and not so much the prize.”

The current official Poet Laureate of Albuquerque is a substantial and effusive Chicano named Manuel González, and he also is a poet’s father. González and his 12-year-old daughter, Sarita, who has read her own works on stage at the Library of Congress in Washington, are in a booth at a café just off Interstate 40, trying to divine Forrest Fenn’s ambiguous and infuriating verse.

Having struck out (so far) on the Rio Chama, a treasure-hunter turns to people of the book for help. Who better to decipher a poem than a poet or two?

“It is a really interesting poem,” says Sarita.

“It’s deceptively simple,” her father adds. “’The hint of riches new and old,’” he quotes. “Maybe the riches are history itself.”

“It seems simple, but I’m sure the metaphors mean something to him,” says Manuel. “As I think about it, every house up there is a house of brown. You can’t build a blue house in Santa Fe.”

The Gonzálezes say that “Chama” is the Tewa Indian word for “blaze,” which may mean that (a) the RAV4 has been going down the right road and (b) Forrest Fenn, who has spent decades excavating and/or exploiting Tewa habitations and selling his finds at huge profits, meant his stanzas to be read in the light of a pueblo fire.

“What I am thinking,” Sarita muses, “is that he was really in love with the native culture and trying to look where the sacred spirit ran through warm waters on Indian land.”

Manuel says that, if he found $2-million worth of lucre lying on a rock, he would “take it into the community. We have the poorest schools in the nation here. I would make sure there were classes in art. Art is what helps to heal the wounds inside us.” He often is invited to recite his poetry to children, seeking, in his words, “to get the kids to tell the truth about what they see in the mirror.”

“I’d want to help as many people as possible,” says Sarita. “And keep a nice little percentage for myself.”

To search for, but not find, Forrest Fenn’s hidden treasure is to join a society of losers who salve themselves with the bromide that the hunt itself is the real reward, and that it is great to be outdoors in the High West in the summertime, and that it is a blessing to leave one’s chesterfield and wander where, as J. R. R. Tolkien wrote:

Roads go ever ever on,

Over rock and under tree,

By caves where never sun has shone,

By streams that never find the sea…

“Dear Forrest,” a Colorado woman who calls herself Lolo wrote to Fenn this summer. “I just finished my first long distance thru-hike, the Colorado Trail . . . I stood on the Continental Divide looking down towards the headwaters of Elk Creek and seeing the reminiscence of an old mining cabin perched in the valley below—and I thought to myself I wonder if Forrest has ever rode his horse or hiked from Stoney Pass to Molas Pass, because if he hasn’t I think he would fall in love—just as I am right now.

“So now here I sit two days after finishing the trail, reading your poem for the first time in a long while. Your books lay on the table beside me and I thought I should email you some pictures of my adventure and thank you for inspiring me to stay out there in the wild—exploring and creating my own treasures of memory.”

Ghost Ranch, Skull Bridge, Dead Man’s Peak. The canyon of the Rio Chama.

Perhaps we are only searching for ourselves as we tarry scant along life’s winding trail.

Wrote Friedrich Nietzsche: “Of all mines of treasure, one’s own is the last to be dug up.”

“A thousand men, say, go searchin’ for gold,” reasons Howard, the grizzled old prospector in the classic film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. “After six months, one of them’s lucky: one out of a thousand. His find represents not only his own labour, but that of nine hundred and ninety-nine others to boot. That’s six thousand months, five hundred years, scramblin’ over a mountain, goin’ hungry and thirsty. An ounce of gold, mister, is worth what it is because of the human labour that went into the findin’ and the gettin’ of it.”

“The treasure is going to stay where I hid it until someone finds it, or until there is a land slide, a volcano, a tornado, or some other kind of phenomena,” states Forrest Fenn.

“I cast a bronze bell and signed and dated it,” he says. “On its side, I wrote these words. ‘If you should ever think of me, a thousand years from now, please ring my bell so I will know.’ I buried that bell three feet deep in a beautiful flowered meadow in the Rocky Mountains. I have no idea what will befall that bell, or when. Time goes on for a long time.”