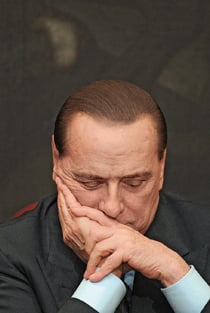

Berlusconi, remember him?

Try as he might to stay under the radar, the scandals just keep piling on

Share

For Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s disgraced former prime minister, staying under the radar is proving a challenge. The humbling experience of having to relinquish power—amid boos—as his country teetered on the brink of financial disaster may have rendered him unusually media shy, but Berlusconi has by no means disappeared. Whenever a new detail or allegation of wrongdoing emerges, the combative septuagenarian is back to defend his honour. According to one recent revelation, he reportedly hired strippers dressed as nuns and soccer stars for his so-called “bunga bunga” sex parties. He has admitted to having wired, last June, roughly $130,000 to three women who participated in the parties; the trio is currently testifying in a trial in which he stands accused of paying for sex with an underage prostitute, and of abuse of power.

The media mogul had a quick response. Of course, the money transfer wasn’t an attempt to corrupt witnesses, he raged in an interview with Il Giornale, a newspaper owned by his brother Paolo. Rather, it was an act of “generosity.” In fact, he’d used a bank transfer, he added, “because the money is transparent, totally traceable.”

To those who have been following him since he first launched his political career in the early 1990s, it is increasingly clear Berlusconi hasn’t been defeated yet. “The man has been up to something ever since he was fired,” quips Italian columnist Beppe Severgnini, author of Mamma Mia! Berlusconi’s Italy Explained For Posterity and Friends Abroad. Although it is unlikely Berlusconi will ever be prime minister again, says Severgnini, he continues to lead his People of Liberty party; the party’s support in parliament is essential for the unelected government of current PM Mario Monti. “The moment the government mentioned two things Berlusconi didn’t quite like”—a plan to sell digital television frequencies and an anti-graft law—“his party was up in arms,” says Severgnini. Both measures could pose a threat to Berlusconi, who owns the country’s three biggest private TV stations and has faced a string of legal cases involving accusations of corruption, embezzlement and bribery.

Still, many Italians blame the entire political elite, not just the former prime minister, for the financial near-catastrophe. A recent survey found that 91 per cent of voters have little or very little confidence in any of the existing political parties. A series of recent, high-profile allegations of fraud that hit both the left and right and led to the resignation of Umberto Bossi, the former head of Italy’s separatist Northern League, haven’t helped matters. Newspapers and political analysts keep looking for promising newcomers, notes Marco Tarchi, professor of political science at the University of Florence. So far he doesn’t see much. It appears this was not simply one’s man’s destruction. Berlusconi’s departure from the stage has left behind a political wasteland.