Standing up to bad boys like Schwarzenegger and Strauss-Kahn

Women all over the world are fighting back against sleazy men, no matter how powerful they are

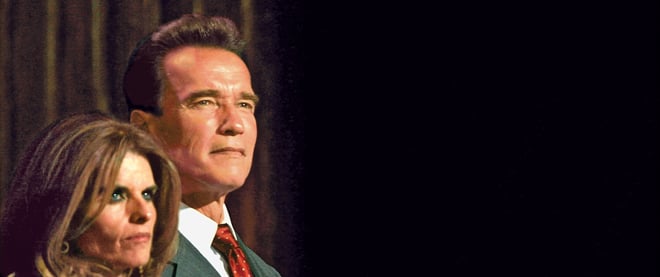

Cancan Chu/Getty Images

Share

On May 17, the same day the Los Angeles Times broke the story that Arnold Schwarzenegger fathered a child with a long-time employee, his estranged wife Maria Shriver was in Chicago, taping the penultimate episode of Oprah Winfrey’s talk show. As the audience cheered, she took the stage to thank Winfrey for her friendship while making a not-so-subtle dig at her husband’s stunning duplicity: “You’ve given me love, support, wisdom, and most of all…the truth.” Winfrey clasped Shriver’s hand, thrust it in the air and cried, “Here’s to the truth!”

It was a classic Oprah moment, perfectly calibrated to the trend of rich and powerful philanderers getting their comeuppance. If Shriver had plotted to orchestrate a public up-yours toward her husband of 25 years, she couldn’t have chosen a more ideal platform. Days later the allegation arrived that she had done just that: TMZ.com reported Shriver herself had leaked the Schwarzenegger story to the Times—a historic moment for a woman born into the Kennedy family, a political dynasty where wives appear hard-wired to ignore infidelities.

For years, Shriver followed that script as rumours swirled about Schwarzenegger’s cheating and sexual assaults. A 2001 Premiere magazine exposé, “Arnold the Barbarian,” claimed the action hero routinely grabbed women’s breasts in some sort of Neanderthal greeting, and repeatedly forced unwanted physical contact. In 2003, on the eve of the California gubernatorial election, six women came forward in the L.A. Times alleging that Schwarzenegger had engaged in sexual bullying and assault dating back decades. Shriver rose to his defence publicly, discrediting his accusers and calling her husband an “A-plus human being,” a validation credited with securing his first landslide victory.

Then, earlier this year, something cracked. Shriver moved out of the family’s Los Angeles estate; in early May the couple jointly, and civilly, announced their separation. A week later, news of Schwarzenegger impregnating Mildred Baena, a 20-year-long household employee, some 13 years ago made for lurid headlines internationally, and the fallout began. The National Fitness Hall of Fame announced it was considering expelling its star inductee after members expressed disapproval and disgust. The former action hero postponed his bid to relaunch his acting career. And California’s attorney general was reported to be conducting an “inquiry” into the former governor’s alleged misuse of state-funded security details to cover up extramarital dalliances. It didn’t end there: Rogelio Baena, the housekeeper’s ex-husband whose name appeared on Schwarzenegger’s child’s birth certificate, is said to be suing the ex-governor on grounds he engaged in conspiracy to falsify a public document.

Schwarzenegger’s public takedown pales, however, next to the potential fate of fellow sexagenarian alpha male, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who was toppled from his position as International Monetary Fund chief after a female worker at New York’s Sofitel hotel accused him of sexual assault on May 14. Strauss-Kahn’s indictment on seven counts of criminal sexual acts, including attempted rape and unlawful imprisonment, which carry a potential total sentence of 74 years, sent shock waves through the Davos crowd and more resoundingly in France, where the popular Socialist party member was seen as a likely successor to President Nicolas Sarkozy in the 2012 presidential election. Strauss-Kahn, out on bail in New York, has denied all of the charges.

Elsewhere, sleazy, sexist, misogynistic and/or criminal behaviour is also coming under public, political and legal censure. This week, in local elections, Italians, finally fed up with Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s ceaseless corruption charges and “bunga bunga” parties, registered disapproval by voting his coalition party out of several key districts, including Milan, the PM’s home turf, and Naples. Last month, Korean politician Kang Yong-Seok was given a six-month suspended sentence and kicked out of parliament after a group of female TV presenters filed a defamation lawsuit against him for asking a group of female journalism students if they were prepared to have sex with their superiors to get ahead. And last week, female employees of Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals in New Jersey launched the latest sexual harassment claim class action, filing a US$100-million suit against the multinational.

Elsewhere, women are taking to the streets like it’s 1968. The SlutWalk protest that had its genesis in Toronto—after a police officer told women that to avoid being sexually assaulted, they should “not dress like sluts” (he immediately apologized)—is now fanning out globally. And protests erupted in New York last week after two police officers were acquitted on charges of raping a drunken woman they were called to assist. (Hours later the men were fired from the force after being found guilty of official misconduct.)

In France there were similar protests, especially after the initial response to the Strauss-Kahn charges revealed the country’s high tolerance for sexual assault and harassment. Initially, the former IMF chief’s defenders blithely dismissed the alleged crime and its victim: one journalist joked about “getting into the maid’s skirts,” while former government minister Jack Lang said, “It’s not like anybody died.” Many viewed Strauss-Kahn himself as the victim of rigid American morality or political conspiracy. Socialist Euro MP Gilles Savary claimed his friend was the victim of a “cultural” gulf between France and the U.S., calling Strauss-Kahn a “libertine” who enjoyed the “pleasures of the flesh,” which was not tolerated in a “puritan America.” The leftist newspaper Libération labelled the situation France’s first “Anglo-Saxon sex scandal,” a descriptor that inflamed feminists by conflating consensual sex with an alleged violent assault.

Nearly 3,000 people turned up at a rally on May 22—with signs proclaiming: “Men play, women pay” and “We are all chambermaids.” More than 28,000, including Carla Bruni-Sarkozy, endorsed the petition “Sexism: they (men) lose it and women pay,” circulated by feminist groups. Strauss-Kahn’s guilt or innocence is not the point, write the organizers: “We do not know what happened in New York last Saturday but we know what is happening in France last week. We are witnessing a rapid ascent to the surface of sexist and reactionary reflexes so quick to arise among some French elites.” The petition denounces not just sexual violence against women but the “daily wave of misogynous commentary coming from public figures” and the “anthology of sexist remarks” in French media and the Internet.

What has made the case a global rallying cry is its textbook power dynamic, says Penelope Andrews, a law professor at City University of New York: “It’s a confluence of class, race and gender.” Strauss-Kahn’s accuser, whose name has not been officially released, has been identified as a 32-year-old from the West African nation of Guinea who sought asylum in the U.S. seven years ago with her daughter. “She’s become a Rosa Parks-type figure,” says American historian Barbara Winslow, a professor at Brooklyn College. “She’s ripe for projection: we don’t know anything about her.”

That’s certainly not the case with Strauss-Kahn and Schwarzenegger, who’ve emerged as transatlantic bookends, fossilized “womanizers” accused publicly of abusing their power. Both are in their 60s, rich, powerful and connected. Both are known by affectionate nicknames—“Arnie” or “the Terminator;” “DSK” or “the Great Seducer.” Each one’s scandals involve female domestic labourers, which lends a frisson of feudal droit du seigneur, the French term for the entitlements of the ruling class. Where they differ is that there is no suggestion that Schwarzenegger’s relationship with Baena wasn’t consensual, though that line can be blurry, says Andrews. “If you have a housekeeper in your house—a maid—how much consent can you infer?” she asks.

What has stoked anger toward Schwarzenegger and Strauss-Kahn is the fact that their predilections were well known, but ignored to a great degree. Over the years, the media flirted with exposing both men’s behaviour. In a 2007 television interview, Tristane Banon, the goddaughter of Strauss-Kahn’s second wife, Brigitte Guillemette, accused Strauss-Kahn (his name was beeped out) of attempted rape in 2002, likening his behaviour to that of a “rutting chimpanzee.” In 2007, journalist Jean Quatremer issued a warning on his blog about the risks of appointing Strauss-Kahn to the IMF. “The only real problem with Strauss-Kahn is his attitude to women. Too insistent, he often verges on harassment,” he wrote, adding: “The IMF is an international institution with ‘Anglo-Saxon morals.’ One inappropriate gesture, one unfortunate comment, and there will be a media hue and cry.”

On cue, Strauss-Kahn was forced to publicly apologize the next year for conducting an affair with a subordinate—Piroska M. Nagy, a Hungarian economist—after an internal investigation concluded he showed “poor judgment” and acted improperly, though without abusing his power. In a letter to the IMF board later, Nagy disagreed, saying Strauss-Kahn had exploited his position to become intimate with her. “I was damned if I did and damned if I didn’t,” she wrote, going on to say Strauss-Kahn was “a man with a problem that may make him ill-equipped to lead an institution where women work under his command.”

In Schwarzenegger’s case, the media had a field day with the 2003 sexual harassment allegations, which prompted the soon-to-be Governator to issue a back-handed apology admitting he had “behaved badly sometimes,” but that the women didn’t understand it was all in fun. “Yes, it is true that I was on rowdy movie sets and I have done things that were not right which I thought then was playful,” he said, “but now I recognize that I have offended people.” Still, the jokey quality of the coverage—the affair was dubbed “Grope-gate”—indicated that the U.S. media did not take the story seriously.

France, meanwhile, prides itself on not prying into what politicians get up to in the bedroom—François Mitterrand, for instance, famously had a child with his mistress, though she never worked in his home. But that also means non-consensual sexual behaviour gets a pass as well. America represents the opposite end of the same spectrum: the ceaseless parade of philandering politicians and sexual exploits has inured the public to more serious allegations of sexual violence or harassment when they arise.

The simultaneous timing of the two men’s disgrace has definitely been a conversation starter, says Andrews: “It’s as if feminism has been revitalized.” In Women’s eNews, Sandra Kobrin coined the term “Tipper Point,” after Tipper Gore, as: “the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point where a wife can no longer stand for the sexual philandering, sexual abuse or gross misconduct of her rich and powerful husband.” It’s far from a bulletproof theory: for starters, there’s no evidence Tipper Gore left her marriage for that reason. And Anne Sinclair, Strauss-Kahn’s third wife, appears steadfast. But a tradition of wives refusing to accept brazen philandering has emerged, from Elizabeth Edwards, who spent her last days crusading against husband and former presidential candidate John Edwards, to Elin Nordegren, Tiger Woods’s ex.

A boiling point has been reached, says Winslow. “There is a lot of pent-up rage and frustration in the United States,” she says, “by a lot of politically conscious women, about all the crap we’ve had to take in the last 10 years: the attack on women’s rights to reproductive health, the attack on teachers, the attack on the social welfare system—and listening to the debate about ‘When is rape really rape?’ ”—a topic that outrages her, given that the answer is clearly whether consent exists.

In that latter debate, Kathleen Lahey, a law professor at Queen’s University, cites last week’s Supreme Court of Canada decision as a positive step in more clearly spelling out at least one of the limits on “consent.” According to the court, a woman can consent to being strangled into unconsciousness as part of a sexual encounter, but any further sexual activity is legally classified as sexual assault until she regains consciousness and has the awareness to consent to those specific further acts. As Lahey sees it, the case has implications for the sorts of cases surrounding Schwarzenegger and Strauss-Kahn: “As the law of sexual assault is updated to focus more clearly on the crucial element of genuine consent (which is where women’s experience of the event can come into evidence), perhaps the assumed prerogatives of the ‘alpha male’ types will be seen for what they really are—sexual assault.”

French Finance Minister Christine Lagarde, currently a front-runner to replace Strauss-Kahn at the IMF, has said his case could be France’s “Anita Hill moment”—a reference to the female lawyer who, in her landmark 1981 testimony during current Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s confirmation hearings, accused Thomas of sexually harassing her in the workplace. It proved to be a divisive yet defining moment for sexual harassment awareness. “I think there will be a pre-DSK and a post-DSK,” Lagarde told the New York Times. “And things that may have been tolerated or generally accepted as okay will no longer be.”

Already, women in France are standing up to chauvinistic behaviour. Banon has lodged a complaint against Strauss-Kahn with police. This week, Georges Tron, Sarkozy’s public works minister, stepped down after prosecutors opened a preliminary investigation into accusations of sexual aggression and rape brought against him last November by two women who worked in the town hall of the Paris suburb where Tron was previously mayor. Tron has dismissed the allegations, claiming his political rivals were trying to gain momentum from Strauss-Kahn’s arrest. But one of the women told Le Parisien newspaper that that episode was what inspired her to speak out: “When I see that a chambermaid was capable of taking on Dominique Strauss-Kahn, I tell myself I don’t have the right to stay silent.”

Change in France will take time, says Amy Mazur, a political science professor at Washington State University who specializes in feminist issues in France. “Policy change at the national level is difficult because of entrenched institutional gender norms. You’ve got a lot of political resistance to saying someone of DSK’s calibre is a sexual predator.” That said, she observes his arrest could provide a “critical juncture” moment of change: “International outrage is important in that it allows French feminists to use extra-national forces which could be a tipping point that affects France in a bigger way. EU influence could play a big role as well.”

Already, the Strauss-Kahn case has also lifted a rock to expose allegations of systemic sexual abuse at the IMF, the institution he formerly headed and where U.S. law does not apply. One woman told the New York Times that she got poor job performance reviews after refusing to continue sleeping with a supervisor. Another complained to superiors when her manager sent sexually explicit emails, but no disciplinary action was taken. The situation was so dire some female employees stopped wearing skirts for fear of attracting unwanted attention. A new, tougher code of conduct adopted on May 6 specifies that intimate relationships with subordinates “are likely to result in conflicts of interest” and “must be disclosed to the proper authorities.”

Stories that shed light on the vulnerabilty of female hotel workers are also emerging—including tales of naked men screaming “I need sex!” This week, Mahmoud Abdel Salam Omar, 74, a prominent former Egyptian bank chairman staying at New York’s luxury Pierre hotel, was charged with sexually assaulting a maid who brought him a box of Kleenex. Labour groups and hotel housekeepers have reported at least 10 other attacks in recent years; many are hushed up because the victims are illegal immigrants or the hotels are afraid it will affect business. Earlier this week, days after New York assemblyman Rory Lancman called for legislation that would ensure maids were equipped with panic buttons, Sofitel announced a change in its uniform code, allowing female employees to wear pants.

“There’s a definite mobilization,” says Andrews. But Jennifer Pozner, executive director of Women In Media & News in New York, wonders whether simply aiming the media spotlight on men who abuse their power is enough. “Are those pieces linking their violence and abuses of power to systemic and political machinations that allow them to continue to abuse power with impunity? Or are we just looking at them as sex scandals rather than violent criminal acts that they are empowered to make because of the power structures they preside over?” It’s an important distinction, one that will require a seismic shift in awareness, one Dominique Strauss-Kahn appears to be taking small steps toward: this week it was reported the domestic staff he hired for his New York townhouse is all male.