That Brexit graffiti: One picture, nearly 1,000 words

What do the U.K.’s Boris Johnson and the U.S.’s Donald Trump, depicted locking lips, have in common? A story about taking back control of a nation

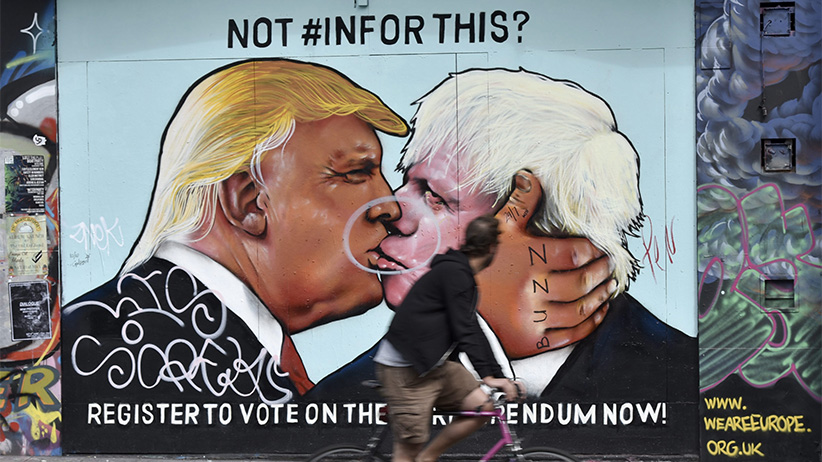

A cyclist takes a look at a painted image of former London Mayor Boris Johnson (R) and US Presidential candidate Donald Trump (L) in Stokes Croft in Bristol, Britain, 30 May 2016. Boris Johnson is supporting the Brexit campaign, ahead of a referendum on whether Britain should remain in or leave the EU on 23 June. (NEIL MUNNS/EPA/CP)

Share

The problem with Europe, historian Tony Judt wrote in 1995, was that the Union was quickly becoming divided—even then, barely two years after the Maastricht Treaty created the EU–into winners and losers.

The winners were, in Judt’s estimation, those living and working in “golden triangles” of economic success. The losers: the poor or disadvantaged (educationally and linguistically) and those “for whom ‘Brussels’ is at best an administrative abstraction, at worst a politically targeted object of fear and loathing.”

Judt thought he knew what might happen to these so-called losers: they would turn away from the grand European political experiment, and back to the old boundaries they used to know. “The risk,” he wrote, “is that what remains to these Europeans is the ‘nation,’ or, more precisely, nationalism.”

And he wondered, if “Europe” comes to stand only for its winners, then “who speaks for the ‘losers’ ”?

Now, it is June 2016, and we might have an answer.

In three weeks, the people of Britain will vote on whether they wish to remain part of the European Union. And if former London mayor and current Conservative MP Boris Johnson has anything to do with it, Britons will decide they do not.

Johnson’s argument against remaining in the EU is essentially twofold: first, that exiting the EU would benefit the U.K. economically, and second, that it would restore the U.K.’s democratic agency. But of course, it is not as simple as that. For, as they say, we are often most acutely judged by the company we keep.

Between the groups that agree Britain should leave the EU, relations are frosty. There are three main ones: Vote Leave (to which Johnson is aligned); Leave.EU; and Grassroots Out. The latter is home to Nigel Farage, the controversial head of the UK Independence Party (UKIP). But while Farage and others have loudly proclaimed distance between the three groups, similarities remain. For one thing, none of them are keen on immigrants, specifically the ones that can’t speak English.

Immigration is at the heart of both the democratic and economic arguments Johnson and his pro-exit peers put forth, helped along by daily hysterical headlines of immigrants invading Britain’s shores. Immigration to the U.K. has risen sharply in recent years, and roughly half of net migration totals are thanks to EU citizens. “I am in favour of immigration,” Johnson said earlier this month, “but I am also in favour of control.” It is that last word that seems to be key.

What the EU debate in the U.K boils down to, simplistically, is class, and thus of control. Middle-class Britons tend to favour remaining in the EU; working-class Britons favour leaving. Britons who live in the heart of England—the Midlands, where industry has declined in recent decades—also prefer leaving the EU. Finally, well-educated Britons want to remain in the EU, while their less-educated fellow citizens do not. In fact, education might be the strongest dividing line of all. “When education is controlled for, other factors affecting an individual’s views on Europe—like income, choice of newspaper and even age—diminish,” the Economist reported.

As it happens, while promising Britons more control (over borders, trade, laws), Johnson is seeking some of his own. He has made Brexit a central plank in his bid to splinter the Conservative Party and force out its leader, David Cameron. Johnson may or may not truly believe in all the things he espouses, but he cannot win power and the political control he is said to want without promoting them—even if it divides, or destroys, the very party he wants to lead in the process.

No wonder, then, that We Are Europe, a pro-EU group, chose to depict Johnson locking lips with Donald Trump in the mural the group created in Bristol last week. Johnson is not directly analogous to Trump, but they indeed share an orbit, circling similar populist fears, and hawking a similar story about taking back control of a nation.

Trump’s rhetorical target audience—when he speaks of building walls to block out Mexicans, putting a moratorium on Muslim immigration, getting tough with China and bringing an end to political correctness—are also those who have felt they have lost the most in recent decades. They are working-class and, broadly, like their anti-EU allies in the U.K., less educated. The abstract political target for them is not Brussels, but Washington.

And like Johnson’s in the U.K., Trump’s message is gaining in popularity.

So now, everybody else—those so-called “winners”—looks at this transatlantic “death kiss” (as We Are Europe called their mural) with apprehension and increasing fear that Tony Judt was right about Europe, and that the liberal postwar experiment, along with the consensus it was supposed to create, might have been flawed all along, or at least more fragile than anyone expected. This is a question of control for them, too; they might very well lose it.