The two faces of the Syrian crisis: a toddler and a tech titan

Of symbols, Syrians, and defining images: Anne Kingston explains how the iconography of a moment says more about the viewers than the subjects

By 2008, with the introduction of the MacBook Air, Steve Jobs had shrunk the laptop to once-unthinkable size. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu, File)

Share

On Tuesday, the Daily Mail ran a cartoon that was vile even by the tabloid’s usual standards: a crude depiction of a crowd of refugees presumed to be Syrian (one carries a prayer mat; there’s a woman in a niqab) walking toward a sign that says “Welcome to Europe—Our open borders and the free movement of people.” The threat they pose is conveyed with the jack-hammer subtlety for which the newspaper is known: one man past the sign has a rifle poking out of his backpack, clearly a reference to the speculation that some of those involved in the Paris attack were refugees; rats scuttle through with them. It didn’t take long before someone drew parallels to 1939 Nazi propaganda, specifically a cartoon depicting Jews as less than human, as a swarm of rats thwarted from entering the European countries critical of Germany’s treatment of them.

The newspaper was excoriated, and rightly so. (Given the Mail‘s hate-filled track record, the likelihood that this was adroit social satire is close to zero.) In the process, the cartoon, often juxtaposed with its anti-Semitic antecedent, was widely circulated on social media. And now a cartoon inspired by the Third Reich that reduces refugees to vermin can be added to the polarized and polarizing iconography that has come to define the Syrian refugee crisis, imagery that says less about one of the largest refugee exoduses in history than about those watching it from the outside.

The first defining image, of course, only three months ago, was the photograph of drowned three-year-old Alan Kurdi lying at surf’s edge on a Turkish beach. Millions of Syrians had been fleeing an endless, bloody war for months before that. Children were perishing—as documented in photographs of teddy bears washed ashore. At least 12 other people were known to have perished with Kurdi. But it was a vulnerable child in a red T-shirt and shorts, the uniform of all children, that inspired activism and outrage. Kurdi’s picture was the one held aloft as tens of thousands marched in the streets worldwide.

The response is entirely human. Children elicit protective and primal instincts, which is why they’re used in advertising and why poverty activists speak of “child poverty” as if it can exist independently of poor adults. We recoil from the idea of children placed in peril. More than 40 years ago, a furor was sparked by Nick Ut’s 1972 Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of traumatized children running from a napalm attack in South Vietnam. Our eyes were fixed on the most vulnerable of them: the naked, severely burned nine-year-old Phan Thi Kim Phuc. Like Kim Phuc, Alan Kurdi was unassailably a victim; he served as proxy for many other unseen children—half of Syrian refugees, according to one report. And he posed no threat. His death was a reminder of the huge risks his father was willing to take because staying would be so much worse.

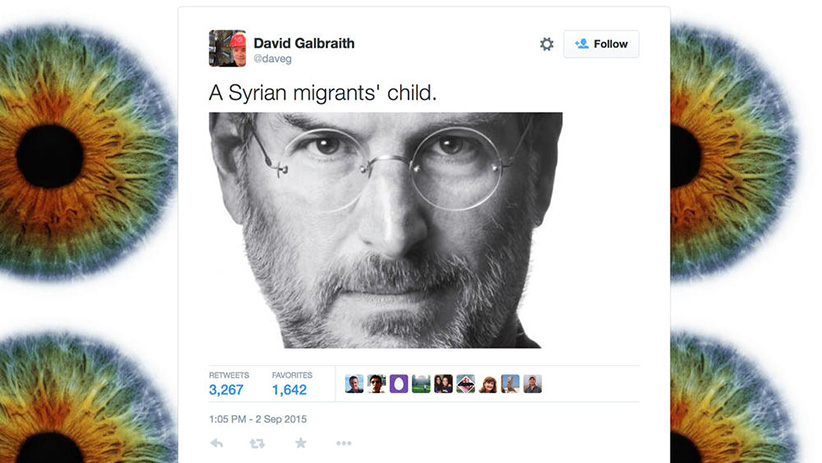

The other defining image of the Syrian crisis springs from another realm entirely. After last week’s Paris attacks revitalized concerns about security risks posed by Syrian refugees, giving rise to the sort of imagery seen in yesterday’s Daily Mail, a figure far more powerful than the three-year-old Alan Kurdi has been marshalled again on social media: pictures of Steve Jobs, defined as “a Syrian migrants’ [sic] child,” even “The son of a Syrian refugee,” are making the rounds. Jobs, adopted at an early age, is the biological son of an American mother, Joanne Carole Schieble, and Abdulfattah Jandali, a Syrian who came to the U.S. in 1954. He was born out out of wedlock and the couple was forced to give him up for adoption. He never met his mother and chose not to have a relationship with his father.

That a dead toddler and a tech titan have become the faces of one of the world’s worst refugee crises is telling. Where the Daily Mail and their ilk rely on dehumanizing refugees, those who are sympathetic have wound up making them unrealistically ultra-human. Most refugees, no matter where from, are not adorable small children. And odds are low that they or their progeny will revolutionize technology, create neat products people the world over clamour to buy, or contribute billions to the economy. They usually end up working jobs beneath their training and education. Some end up driving taxis, which is what Steve Jobs’s biological father did.

We search for a unifying image to make sense, to rally around. But which images resonate with us says a great deal. One of the emblematic images from the Paris attack was the “Paris for Peace” symbol, the spontaneous illustration by a French artist. The other is a haunting photograph by Associated Press photographer Jerome Delay of a body lying on the sidewalk outside the Bataclan Theatre covered by a blanket, illuminated by lamplight. It is also a powerful tribute to humanity. All that is known about this unnamed person is that only hours earlier he or she was enjoying life in a jubilant crowd listening to music, before, in a flash, becoming a victim of life’s circumstance. All we know is that he or she was human, which in the end is all that should matter.