The view from the north

As southern Sudan votes on secession, the president is forced into ‘survival mode’

Share

Millions in southern Sudan lined up this week to cast their ballot in a referendum to decide whether the south should split from the north of the country. After a civil war spanning more than four decades, and half a century of economic neglect and violent persecution at the hands of the government in the north, most people are expected to opt for secession.

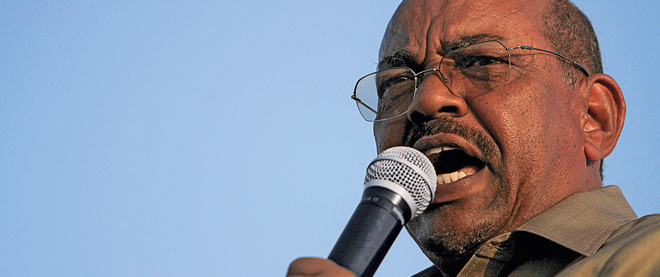

Meanwhile, in Khartoum, which will likely be the capital of a unified Sudan for just a few more months, President Omar al-Bashir is “in survival mode,” says Richard Downie, deputy director of the Africa program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based think tank. Faced with losing a chunk of the country the size of Texas, the Sudanese leader, who led a bloodless coup in 1989 and is accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Darfur, is left to ponder which course of action will keep him in power. Downie says that a slew of conciliatory public statements plus a recent visit to south Sudan shows that al-Bashir is resigned to the idea of separation, and is trying to make nice with the international community. But “he is going to be under a lot of pressure from the hard-liners,” those who don’t accept the referendum, says Stephen Rockel, a professor of history at the University of Toronto. To appease them, al-Bashir is going to need to look tough during negotiations with the south, says Downie. After the results of the referendum are made public later this month, the north and the south have about five months to work out thorny issues like where the new border will be located and, most importantly, how to share oil revenues before actual secession takes place on July 9. It’s over this period, experts warn, that al-Bashir could decide to flex his muscle.

A master in the art of divide and rule, the seasoned dictator may rely on friendly militias in the south to foment disorder and extract more leverage at the table, says Downie. And linking him to the troublemakers would be difficult, he adds, since armed scuffles could plausibly flare up on their own in the ethnically diverse south.

The other major imperative is finding a way to avoid a domino effect. Darfur, in the western part of northern Sudan, would like to be the next region out, but there are several other parts of the country that might grow restive, says Rockel. “There’s going to be a lot of pressure on al-Bashir to hold the line” and keep the country together, he adds.

But even if al-Bashir manages to preserve a unified north, he’s going to find it harder to rule what’s left. State coffers, for starters, are going to take a beating, as many developed oil fields are in the south. In the disputed Abyei region, which both north and south claim, oil production is estimated at $500 million a year, revenue that will now have to be shared. The northern half of Sudan can step up agricultural production, and the government can rely on the returns of foreign investments to keep up its network of patronage for awhile, even if other sources of revenues dry up. But, says Downie, al-Bashir will be left after the secession “juggling the system with fewer resources.”