Portsmouth and the end of an era

While the U.K. mourns the end of its oldest shipyard, some see a cynical political manoeuvre

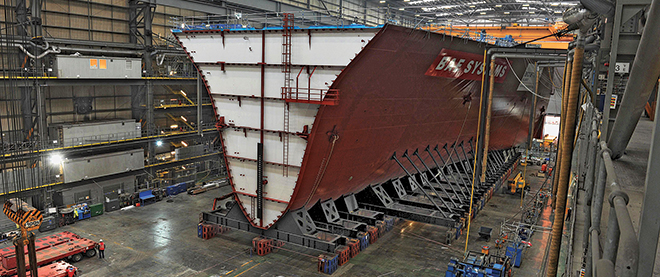

Solent News / Rex Features / CP

Share

It was the end of an era of British naval history when it was announced last week that HMNB Portsmouth, the U.K.’s oldest shipyard, would close its industrial building arm once and for all. For more than 500 years, military vessels have been constructed in the port, which is home to the world’s oldest dry dock, as well as two-thirds of the Royal Navy’s surface fleet.

It was in Portsmouth in 1510 that Henry VIII commissioned the most famous of the Tudor war ships, the Mary Rose—a vessel that later capsized and whose wreckage is on display in the port’s museum. Several ships built there formed a key part of the fleet that helped to ward off the Spanish Armada in 1588. Horatio Nelson embarked from Portsmouth on HMS Victory before sailing to his death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. And the first modern battleship, the original Dreadnought, was built here at the beginning of the 20th century.

It’s no surprise, then, that the reaction to the closure announcement was one of national outpouring—the most vocal of which came from Portsmouth itself. BAE Systems, the British multinational defence, security and aerospace company that runs the U.K.’s shipyards, announced 940 job losses for Portsmouth. There will also be significant reductions in the country’s other major shipbuilding town; more than 800 will be cut in two major shipyards in Glasgow. But the Portsmouth closure is, perversely, good news up north, since it removes the fear of immediate shutdown—something those who labour on the docks are, sadly, well-accustomed to by now.

Philip Hammond, the British secretary of state for defence, was widely criticized for playing politics by ring-fencing Glasgow at the expense of Portsmouth. His critics speculate the coalition government could not afford to close shipyards in Scotland so close to next year’s looming independence referendum, which is why Portsmouth had to go. Hammond, for his part, called the closure “regrettable but inevitable.”

The MP for Portsmouth South, Mike Hancock, told the press that his constituents had “paid a very heavy price for a slightly cynical manoeuvre,” while others questioned the government’s decision to protect industry in a politically fractious region.

The government, however, insisted the Portsmouth closure had come “on the basis of industrial logic,” rather than politics, since the Glasgow yards are better equipped to carry out BAE’s contract to build billions of pounds worth of Type 26 warships, starting in 2015.

It’s a straightforward argument, until you consider what might happen to Britain’s shipbuilding industry if Scotland votes for independence next year. Directly after the BAE announcement, Prime Minister David Cameron said publicly, “If there was an independent Scotland, we would not have any warships at all.” And another government source intimated to the Financial Times that Britain would not be giving out a contract for major military shipbuilding to a foreign country.

Taking this into account, the Portsmouth closure starts to look like a cynical political manoeuvre indeed. By saving jobs in Scotland now, the government may essentially be hoping to secure votes down the road.

It’s a clever strategy, but a risky one, too. With Portsmouth closed, if Scotland votes to leave, who will be left to build British ships?