Tripoli vs. The Hague: two courts vie to try Gadhafi’s son

Libya and the International Criminal Court are at war—over who gets to stage a trial for Saif al-Islam Gadhafi

Share

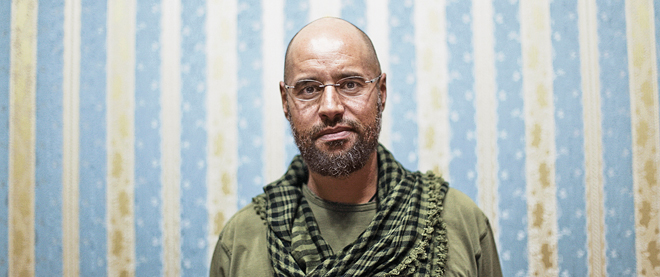

Saif al-Islam Gadhafi, the son and once presumed heir of deposed Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi, says he would rather face the death penalty from a trial in Libya than be tried in an international court that would spare his life.

The International Criminal Court has charged Gadhafi with crimes against humanity related to his alleged role in the suppression of last year’s uprising against his father’s regime. It has ordered Libya’s National Transitional Council to surrender him into its custody in The Hague, in the Netherlands. But the Libyan government insists it will try Gadhafi, and has asked the international court to drop its case against him and his co-accused, former intelligence chief Abdullah al-Senussi, who is now in Mauritania.

Gadhafi sided with the former rebels he once described as “drunkards and thugs” when ICC investigators visited him in Zintan last month; he has been held by an anti-regime militia in the tiny Libyan city since they caught him apparently trying to flee to Niger. “I hope I can be tried here in my country, whether they execute me or not,” he reportedly said.

Gadhafi’s comments might have been made to please his captors. A Libyan prosecutor was present at the time. But Gadhafi did not retract them when the prosecutor left the room. Gadhafi’s judicial fate, however, is not up to him. It will be decided in a legal argument between the ICC and Libya’s fledgling government.

The ICC’s official mandate is not to supplant local justice, but to take on cases in which national courts are unwilling or unable to try indicted individuals themselves. International trials provide a chance for justice that might not otherwise exist, but at a cost. The country where heinous crimes were committed avoids confronting its past, and the judicial process unfolds far from the victims. To critics, the ICC’s desire to try Gadhafi smacks of neo-colonialism, of Western interference in the affairs of a sovereign government trying to deliver justice to its citizens. But the court indicted Gadhafi in June, during the chaos of Libya’s civil war when the country was mostly ungoverned. In a submission to the court, the Libyan government said it “has no intention of shielding such individuals so as to allow impunity, or to hold a rushed trial of these two persons that would not meet international standards of due process. [The government] is committed to attaining the highest international standards both for the conduct of its investigations and any eventual trials. Achieving this outcome will contribute to judicial capacity-building and will provide Libya’s long-suffering people a unique opportunity to assume ownership over the past, to avoid impunity, and to build a better future based on respect for the rule of law and fundamental human rights.”

Amnesty International is not convinced a fair trial in Libya for Gadhafi is possible and has urged the government to surrender him to the ICC. “In the absence of a functioning Libyan court system and for as long as the Libyan justice system remains weak and unable to conduct effective investigations, the ICC will be crucial in delivering accountability in Libya,” Marek Marczynski, a spokesman for Amnesty International’s justice team, said in a statement.

Even if the Libyan government were willing to hand over Gadhafi, it’s unlikely it could currently do so without approval from the Zintan brigade that is holding him, but isn’t under its control. Libya says Gadhafi will soon be transferred to Tripoli, where they are building a special prison facility for him.

In the meantime, Libya is hoping to convince the ICC that it can hold a fair trial. Prime Minister Abdurrahim el-Keib said Libya is adopting new legislation that will incorporate crimes against humanity, war crimes and genocide into Libyan law. He says Libya will liaise with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights regarding any technical assistance that the prosecutors and judiciary might require.

Libya has also hired several top international lawyers to argue on its behalf, including Payam Akhavan, a law professor at McGill University. “The question is whether the judicial system of a country like Libya, after 40 years of dictatorship and tremendous violence, is in a position to allow for a fair trial in accordance with international standards,” Akhavan said in a recent speech at the University of Ottawa. “This is a unique case because it revolves around the question of the ability—as opposed to the willingness—of states to bring such crimes before their own courts.”

Darryl Robinson, a former adviser to the ICC who teaches law at Queen’s University, believes Libya should be given the chance to prove it can deliver impartial justice and, if so, to try Gadhafi at home. “Local justice is close to the victims,” he said. “It’s the site where [the crimes] happened. Success for the ICC doesn’t have to be grabbing the case. Success for the ICC could be the fact that it induced a state to run a high-quality investigation and prosecution for the most serious international crimes.” An ICC decision on whether to proceed with the case is expected within weeks.