What went wrong in Mosul

Iraqi forces were losing the battle. Then the airstrikes began, turning the tide—but at a horrible cost. Inside the terrifying fight for Mosul.

Mosul, Iraq Iraqi army soldiers celebrate the defeat of ISIS in east Mosul. (Photograph by Adnan Khan)

Share

First Lieutenant Yousuf had a reputation for geniality. Blessed with a boyish charm and passable English, the officer with Iraq’s Special Operations Forces was the ideal person to man the checkpoint at Bartella, leading into east Mosul. No one else could quite handle the hordes of reporters who would line up behind a pair of armoured humvees blocking the road.

Every morning, as civilians fled the offensive launched on Oct. 17 to re-take the city from the so-called Islamic State, Lieutenant Yousuf negotiated with those hoping to go the other way.

On any given day, some were granted permission; others were not. Yousuf would juggle the hot potato of access expertly, always with a smile and a handshake, spinning rejection into a kind of fellowship of kindred spirits: he wanted to be there as well, he would say, at the front, battling the fanatics.

But on the morning of Nov. 5, things were different. The Bartella checkpoint was teeming with an unusual number of people. Yusuf sat gruffly in a plastic lawn chair next to one of the battered humvees. When people approached, he would scare them off with a menacing bark.

“He lost some friends at the front yesterday,” one observer said. “He’s not in the mood for the media.”

Nov. 4 had been a rough day for Yousuf’s comrades in the Special Forces, known as the Golden Division. After making lightning-fast advances—nearly a kilometre a day on average over the preceding week—they had pushed into Mosul’s eastern suburbs.

Gogjali, a ramshackle neighbourhood of concrete homes and broken roads, had been liberated on Nov. 2. Taking advantage of its momentum, the Golden Division had then pushed even deeper, reaching the edge of the Hay al-Karama neighbourhood on Nov. 3.

Gogjali, a ramshackle neighbourhood of concrete homes and broken roads, had been liberated on Nov. 2. Taking advantage of its momentum, the Golden Division had then pushed even deeper, reaching the edge of the Hay al-Karama neighbourhood on Nov. 3.

The speed of the advance had proven costly. Thinking ISIS fighters were on the run, the Golden Division had neglected to carry out proper clearing operations. On Nov. 3, ISIS fighters who had taken advantage of a series of tunnels they had constructed before the offensive began, snuck in behind the Golden Division’s frontlines. On Nov. 4 they attacked from all sides, sowing confusion and forcing the Golden Division to retreat.

The battle was still raging on the morning of Nov. 5. At the Bartella checkpoint, frustrated journalists watched as a steady flow of ambulances raced out of the battle zone. The rat-a-tat-tat of assault rifles pierced the cool morning air. American forces, who had set up a temporary base a few kilometres down the road, launched artillery shells into Mosul. They shook the earth as they were fired and landed with a dull thud somewhere in Mosul.

The intensity of the battle took many by surprise. After nearly three weeks of fighting, it had looked as if ISIS was on the run. Towns and villages surrounding Mosul had fallen with relative ease. In the face of a coalition that included tens of thousands of Kurds aligned with more than 100,000 Arab Iraqis—including the Special Forces, Counter-terrorism Service, regular army, and Shia militias—they had cut their losses and retreated.

Whether it was a tactical retreat will be a topic of debate among military experts. No doubt ISIS war planners were well aware of the specific challenges that a city like Mosul posed. Its compact neighbourhoods were not conducive to the heavy machinery the Iraqi military fielded. The presence of an estimated one million civilians offered small groups of mobile ISIS fighters a ready store of human shields that eliminated the clear military targets the U.S.-led air coalition needed to approve airstrikes. And the terrain in and around the city was flat, lacking the high ground so crucial to setting up effective command and control centres.

On Nov. 5, the Golden Division crashed headlong into this punishing reality. The offensive ground to a halt. Senior commanders scrambled to come up with new tactics that could counter the small groups of ISIS fighters they faced, the bomb-laden vehicles they hurled at them, and the streets packed with civilians that rendered their heavy weaponry useless. A different category of warfare would be needed, and one for which the Golden Division was ill-prepared.

In early January, Major John Spencer, a scholar with the Modern War Institute at West Point, published an article warning that the world’s militaries were remarkably unprepared for the realities of urban conflict in the 21st century. Decades of urbanization, he pointed out, had changed the landscape of war. Megacities had become the backdrop to many of the most horrifying battles the world had witnessed—Sarajevo, Mogadishu, Grozny and Baghdad, to name a few. “Yet we still do not have units that are even remotely prepared to operate in megacities,” Spencer wrote.

He wasn’t the first to notice. Since at least 2000, the U.S. military had been grappling with ways to fight battles in cities rather than for cities, Spencer wrote. Prevailing doctrines—sieges, for instance—harked back to Homer and the wars of centuries past. In the modern context, where cities are liberated rather than conquered, long, drawn out sieges did not work. They weakened the enemy but in the process also harmed civilians—the very people being “liberated”—in the most grotesque of ways.

Liberating Mosul from the clutches of ISIS was supposed be an act of emancipation. It was not something that could be done while at the same time slaughtering civilians. For the Golden Division, this proved complicated. In the wake of the early November fiasco, the offensive had slowed to a snail’s pace. Caution ruled the day. The coalition air support that had proved so central to the Kurds as they rolled through towns and villages largely devoid of civilians dried up when the Golden Division took over the fight on the outskirts of Mosul.

“We call in an airstrike and it never comes,” one commander at the Hay al Aden frontlines told me in late November. “The problem is the civilians. There are too many of them.”

The Golden Division was forced to move forward at a punishingly slow pace. A column of armoured humvees led by a tank and an armoured bulldozer would enter a street. The tank was the hammerhead. It would blast away at any signs of ISIS snipers and ambush teams. The militants would take pot shots and then retreat. The bulldozer would then quickly set up barriers to block off access to ISIS suicide vehicles. The soldiers in the humvees would then fan out and clear the street of any remaining ISIS fighters and look for any booby traps they may have set.

The tactics were working but the slow pace of it left the Golden Division vulnerable to suicide attacks, snipers and mortars. The offensive turned into a war of attrition, and ISIS was winning. It was losing territory as it retreated but in the process, it was exhausting and whittling down the Golden Division’s numbers. These were Iraq’s elite fighters, men who had been trained by U.S. and Jordanian Special Forces. They were hard to replace.

By the end of the first week of December, the Golden Division had inched forward and controlled an estimated one third of Mosul’s east. But its morale was dangerously low. Most of the soldiers were Shia Muslims from Iraq’s south and had not seen their families in weeks. Many, like Lieutenant Yousuf, had lost dear friends to ISIS’s brutal guerrilla tactics. Rumours had even begun to spread that some soldiers who had headed home on leave were deserting.

The decision was made to take a pause in the offensive. As many as 5,000 federal policemen were redeployed from areas south of Mosul to replenish Golden Division numbers on the eastern front. According to commanders who spoke to Maclean’s in late January, another decision was also made—one that would change the face of the offensive.

Abdurrahman was sound asleep when the first bomb hit his home. It was 6 a.m. on Jan. 6, and the force of the blast sent fragments of the ceiling crashing down onto his bed. He thought at first he was dreaming. For nearly two weeks, after the Iraqi army had resumed its offensive, his neighbourhood, Hay al Taqafah, and others around it had become the epicentre of fierce battles. Bombs were falling everywhere, Abdurrahman, 19, recalls. The intensity of the airstrikes was nothing like he had experienced when the offensive first began. “It was like living in hell. It was so bad I thought the bombs had entered my dreams.”

But this was no dream. Abdurrahman barely escaped with his life as a series of airstrikes levelled his home. His parents and younger brother were not so lucky. They perished along with 15 other family members who lived in the two houses next to his, which were also targeted. While visiting the site recently, a neighbour told me there were no ISIS fighters in the area during the airstrikes. A Golden Division commander present told him to keep his mouth shut. “Stop telling lies,” he barked.

Phase 2 of the Mosul offensive, beginning on Dec. 27, was different from Phase 1 in at least two crucial respects. Federal police reinforcements had freed up Golden Division units for a final push to oust ISIS from Eastern Mosul. More importantly, Iraqi war planners had decided to up the ante in the use of their most devastating weapon: airstrikes. ISIS fighters had shown remarkable adaptability to counter any tactical changes the Golden Division made. When it slowed down and became more careful, the militants unleashed swarms of weaponized drones. They dropped grenades on the heads of Iraqi soldiers, adding a new dimension to the threats they faced.

But there was nothing ISIS could do against airstrikes. According to Brigadier General Matthew C. Isler, deputy commander of the coalition air campaign, Iraqi F16 fighter jets dropped 95 precision munitions in January, a 40 per cent increase over the previous months. “January was the most successful month for the Iraqi air force,” he told me by Skype from Baghdad. “Their strikes are precise; they hit what they’re after.”

For Abdurrahman, the accuracy of the strike was not in question. It precisely hit the three homes owned by his family while leaving a neighbour’s home only slightly damaged. The question he had was simply: “Why us?”

According to Isler, the coalition air campaign is exceedingly careful to avoid civilian casualties. “We start from characterizing the area before the Iraqi army even gets there,” he says. “As a target nomination comes in, we plot it on the front screen to know where the position of the friendly forces are and other factors of the battle space, like where is the civilian pattern of life that we’ve mapped out previously. And then we use a separate system to predict the weapon’s effects so we can see if we deliver a weapon there, what will be the collateral damage. We’ll weigh the military necessity with the probability of collateral damage.”

It sounds meticulous in theory, but in practice battlefields are never so cooperative. ISIS, for instance, is known to move civilians around with them to provide human shields. The “civilian pattern of life” is not static, reducing intelligence and reconnaissance to best guesses.

In Abdurrahman’s case, it is possible ISIS militants were using his home to mount attacks, though the statements of neighbours suggest otherwise. ISIS fighters often set themselves up on the rooftops of homes, using civilian cover for sniper positions. According to the air coalition website’s daily Strike Release updates, which publicize airstrikes carried out by the U.S. and its allies, a Jan. 6 strike “destroyed three ISIL-held buildings.” Maclean’s was not able to verify if this was the same strike that hit Abdurrahman, but if it was, it also killed 18 civilians.

Was it worth it?

[rdm-gallery id=’1223′ slug=’battle-for-mosul’]

By the end of Phase 1, Iraqi war planners and their U.S. advisers were well aware that if the pace of the offensive did not pick up, there was a very real possibility of it failing. The war of attrition favoured ISIS.

“Every one of our soldiers killed is the equivalent of ten of theirs,” Major General Fadhil Barwari, a commander with the Golden Division said last November, meaning for every Golden Division soldier lost, ISIS gains disproportionately in relative strength.

The decision to increase airstrikes for Phase 2 was then likely a “military necessity” in the estimation of both the U.S. and the Iraqis. And its effects were immediate. During Phase 1, the Golden Division managed to liberate only one-third of eastern Mosul after a costly six weeks. Phase 2 began on Dec. 27, and in three weeks the remaining two-thirds of the city fell.

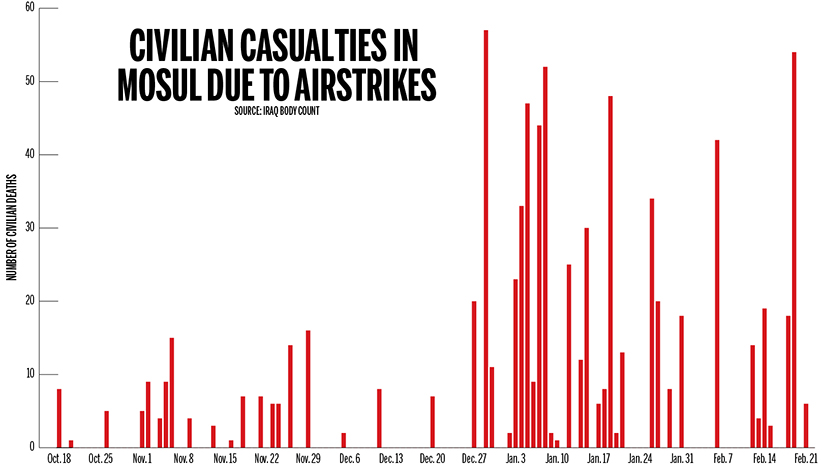

The rapid victory left devastation in its wake, both in terms of damage to infrastructure and the loss of innocent lives. According to Iraq Body Count, which tracks civilian casualties, deaths due to coalition and Iraqi airstrikes soared during Phase 2.

All the Iraqi commanders who spoke to Maclean’s in January and February attributed the success of Phase 2 to airstrikes. Civilians also confirmed, with some lingering bitterness, that the pace of the strikes was deafening. Interestingly, however, based on the air coalition’s Strike Releases, which does not include airstrikes carried out by the Iraqi air force, the number of strikes during Phase 2 actually decreased by around 10 per cent compared to Phase 1.

The uptick, then, must have been due to increased Iraqi air force involvement.

Yousuf’s bitterness, like that of his brothers-in-arms who faced ISIS’s dirty tactics, has seeped into the bone. Liberating Mosul now has little to do with reclaiming Iraqi territory from a brutal interloper; it is a matter of revenge.

The grotesque signs of payback are rapidly emerging in east Mosul: mutilated bodies left to rot on the rubble heaps of the city, men with hands bound behind their backs, legs lashed together, faces half blown off. On the road to Mosul, in front of a Golden Division base in Bartella, a badly decomposed body has been strung from a utility pole, “as a warning to any Daesh sympathizers,” says a Golden Division soldier.

Civilians, both in the liberated east and the ISIS-occupied west, face a reckoning. In the east, rumours of ISIS sleeper cells were validated in early February after a series of suicide attacks rocked the city. ISIS’s weaponized drones continuously buzz over markets and residential neighbourhoods dropping grenades on groups of unsuspecting people in seemingly random attempts to spread terror.

More worryingly, as the Golden Division passes on security responsibilities to the Iraqi army and federal police, east Mosul’s predominantly Sunni Muslim civilians face the prospect of an upsurge in revenge killings. Mixed in with the incoming soldiers, according to reports gleaned from Iraqi officials, are members of the Popular Mobilisation Units, a paramilitary force made up of Shia militias, some of whom harbour apocalyptic visions of an imminent, world-ending battle between Shia and Sunnis. In their eyes, everyone in Mosul is an ISIS sympathizer.

Civilians in the west arguably face an even more grim future. Phase 3 of the Mosul offensive was launched on Feb. 19 from Iraqi positions south of the city. It began with a massive show of strength: tanks lurching to the front, artillery batteries and mortar teams taking positions on a ridgeline overlooking its southern suburbs, warplanes screeching overhead. On its first day, Iraq Body Count reported 54 deaths due to airstrikes, the highest tally since the start of Phase 2.

And the worst is yet to come. Given the layout of west Mosul’s urban centre, airstrikes and artillery will come more into play. The old city, with its maze of narrow laneways and tightly packed buildings, gives the tactical advantage to the more mobile ISIS fighters, who have had more than two and a half years to prepare for this battle. They will use everything in their arsenal in a frenzied fight to the death, including booby traps, suicide bombers and improvised explosive devices.

According to activists in west Mosul, ISIS fighters have already started to retreat into the old city and set up barricades. If the doctrine of military necessity is applied as it was during Phase 2 in the east—which seems likely—civilians will pay the price.

For soldiers like Yousuf in the Golden Division and others in Iraq’s myriad security services, however, the cost is worth it. In their estimation, anyone still left under ISIS control is clearly a sympathizer. “Why else would they still be there?” one federal policeman near the frontlines told Maclean’s recently.

With so many factors stacked against them, many of Mosul’s civilians are up against diminishing odds of survival. It seems inevitable now that ISIS in Iraq will be defeated. But the ghosts of this war will haunt Iraqis for years to come.