Why Canada has a major role to play in rebuilding Iraq

In Iraq, Canada has taken the lead in getting the lights on, the water running and the children back in school—’These kids need to believe in their future’

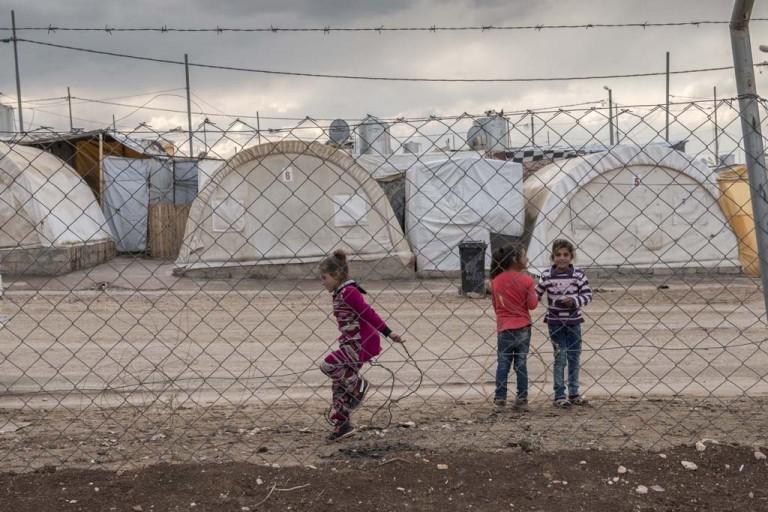

Children play within the Duhok refugee camp in Iraq (Photograph by

Peter Bregg)

Share

One year after Canada pledged $1.6 billion to war-torn Iraq over the next three years, there is a sudden change in the relationship. Any day now, Canada will announce its first resident ambassador to the country in a quarter century, a Yazidi rescue program has been launched and the minister of International Development and La Francophonie, Marie-Claude Bibeau, dropped into Baghdad on Feb. 22. One might ask what Canada is up to in the world capital of terrorism, corruption and human rights offences. “The situation here is a global threat to our security,” says Bibeau. “It’s in our interest to establish stability.”

It’s a tall order: a divided nation state, acres of displaced persons with animosity and distrust writ large. The Kurds and Iraqis have an uneasy bond. The Sunnis and Shia are still taking revenge on one another. Yazidis and Christians don’t think they can trust anyone. And the common enemy other than the barbaric Islamic State is the international community. Everyone from shepherds to executives says this bloodbath could have been prevented. Suddenly the future in this place is on everyone’s to-do list. Iraq has become the centre of the universe when it comes to rescue and rehabilitation. While Islamic State used social media to manage their campaign, today the policy wonks and decision-makers all over the country are on Whatsapp to share their mandates and broadcast their conclusions. Seventh-century barbarism and 21st-century high tech are sharing a stage in the country that calls itself the birthplace of civilization.

As the fight for western Mosul continues, with thousands of troops massed on the Tigris River bank, Brig. Gen. David Anderson, the Canadian senior officer in the coalition headquarters in Baghdad tells Maclean’s, “What happens here affects the rest of the world. Iraq is the focal point of a conflict between a violent extremism and a regional approach. It’s a geopolitical game. Taking Daesh, a truly evil enemy, out is having a big impact on their ability in the rest of the world. By stopping them here, we’re stopping the ISIL-inspired attacks elsewhere.”

Although the taking of Mosul is not the end of the caliphate—there are still towns like Telafar and Hawija and several pockets under their control—the eventual end of the caliphate won’t mean the end of the hateful ideology. And that’s also where Canada is playing a major role. “It’s important to do the humanitarian work we’re here to do but you need development work to have stability,” says Bibeau. To that end, Canada has taken the lead in the Coalition of Working Groups—68 countries tasked with getting the lights on, the water running, the kids back in school. “If the children are in school they are less attracted to armed groups. These kids need to believe in their future,” she says.

Indeed, the future is uncertain, says Farhad Ameen Atrushi, the governor of Duhok, a province that is straining to deal with 400,000 refugees. “It’s all about Nineveh, the largest province in all of Iraq,” he says. “There are Arabs and Christians, Yazidis and Turkmen, Sunni and Shia, Armenians, Assyrians and Kurds.” It’s a complicated tapestry, he says, because almost all the people in Nineveh are original people—their ancient roots are there. After Daesh attacked there were only Muslims left. “It was like a cleansing,” he says. And although western Mosul is expected to fall within four to eight weeks, the governor says Islamic State is very mobile, very capable of taking over and controlling another village because there are still people who agree with them.

For example, in Shingal Mountain (also called Sinjar), the ancestral home of the Yazidis, which is still mostly deserted, Lt. Col. Jadan Darwesh, a Peshmerga soldier, points out the mass graves and the Aleppo-like destruction, and to the smoke in a village two kilometres away. “That’s Daesh over there,” he says. “They use car bombs, human shields and chemical weapons when they attack.” The Peshmerga are waiting for orders from the coalition forces to take out this particular pocket of Islamic State, but Darwesh says foreign reinforcements are still joining them.

[rdm-gallery id=’1235′ slug=’kurdistan’]

Governor Atrushi says, “Today Nineveh is a test ground for all of Iraq. Can these people go home? Can they reconcile? If not, it will be the beginning of the break-up of Iraq.”

But like Brig. Gen. Anderson, he is hopeful. The population of this hardscrabble country of hills and valleys covered in a thin layer of topsoil and deep roots of suspicion is mostly young people who are fed up with sectarian divisions and old-school quarrels. In fact, 60 per cent of the population is under the age of 25, and they are focused on jobs, the economy and opportunity.

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), an erstwhile independent nation (politically correct Canada refers to them as the Kurdistan Region of Iraq or KRI), sees Canada’s investment as a welcome change. “We’re open for business with Canada,” says Falah Mustafa, minister of International Relations. “Terrorism has shown us the world is connected. Migration has shown us the same thing. So has the environment. We can help each other to build strong institutions.” He hopes Canada will open a consulate office in Erbil to promote trade but he knows that the first order of business is binding the wounds of the people who were so terribly brutalized in this war and opening the minds of those who still side with Daesh. “We live in a dangerous neighbourhood. We need to use education, culture, music and art to counter the message of ISIS and stop the recruitment.”

More than 500 Kurds joined Daesh through Donald Trump-like xenophobia that led to a barbaric bloodbath. Yazidi girls tell horrific stories about being taken as sex slaves and escaping from Daesh and fleeing to an Arab neighbour’s house only to be turned back to Daesh. Hussein Hasoon, a member of the High Government Commission on the Recognition of Genocide Against Yazidis, Kurds and Other Religious and Ethnic Groups, says, “I remember when we were fleeing up Shingal Mountain, we were calling our Arab neighbours, people we played football with, and asking them to rescue our belongings, our money.” But later, he says, when the Yazidi survivors of the initial assault went to get their valuables, they were gone, and their Arab friends had become enemies who turned them over to Islamic State.

As the fight for the last half of Mosul continues, Brig. Gen. Anderson says, “Morale in ISIL is plummeting, the leadership is moving away from the action. We have many indicators that suggest they will end up in the desert west of the Iraq-Syria border.”

Governor Atrushi points out an increasingly valid criticism of the international community. “The world focused on this place because of trouble and trauma. We need to focus on reconstruction and development rather than the barbaric actions of Daesh.” He’s a pragmatist who doesn’t lack a sense of humour amidst the seriously difficult task at hand. When asked how he thinks President Trump will impact his territory, he breaks into hearty laughter and calls to an aide, “Bring me the gift.” A colonel from the U.S. army who served here in 1991 had stopped by to visit the governor that morning and brought him a gift. With unabashed glee, Atrushi stands the gift on the table beside him. It’s a Trump bobblehead doll. Then he picks it up and says, “Look, it’s made in China.”

The Canadian effort here is to fly the flag and let Iraqis know Canada is here to help. The Canadian Embassy is doing this with all the usual suspects and issues—the World Food Program (WFP), UNICEF, governance, women’s rights, mine clearing. But this is a new version of aid. For example, the WFP has ditched its program of handing out a basket of nutritious food to each family in need and replaced it with cash for food. The results are impressive. The local markets recover in a matter of days, the food the refugees buy is what their families prefer and dignity is preserved as people go to market with cash like everyone else. Still, the long lineup in the Duhok Sport Center to get the designated cash package speaks of a thousand agonies. One woman, who is too terrified of Islamic State to allow her name to be used, tells her story. She’s a doctor, a gynecologist from Mosul. She’s also a professor at the medical school at the University of Mosul. She and her family managed to escape Mosul last June with absolutely nothing. And now she stands in a line to collect US$17 per family member to survive. She’s grateful for the support, but like so many others is stunned by what happened to them—the brutality, the rapid action of Islamic State and the length of time it has taken to get on the radar of the world.

On the outskirts of Duhok, not far from the camps that each house 10,000 refugees in row upon row of white tents and gravel roads, the mine-clearing crews also bring a new accounting to explosives as well as the size of the barbarism of Daesh. Says Jim O’Neil, director of the Janus de-mining site, “This isn’t the sort of mine used to mark territory. These are mostly improvised explosive devices meant to punish, to take revenge.” He says the devices are hidden in fridges and stoves and closets; some are in the shape of children’s toys. They aren’t for killing soldiers. They’re for murdering infidels.

Even UNICEF has ratcheted up their program to deal with the psychological horror of this war. In what they call child-friendly spaces, kids write their stories, script them into plays and act out their traumas. They laugh and cheer each other on, but the haunting looks on their little faces makes an onlooker know they are too wise for their years, too needy for words.

At a meeting in Erbil, the leaders of half a dozen women’s groups share their stories. The Canadian goal of investing in women is to make sure they have a voice in the new administration of areas being liberated from Islamic State. This group is a noisy, diverse, committed collection of lawyers, writers and activists who claim there are different laws in KRG and in Iraq. For example, honour killing is a crime in KRG and still legal in Iraq. While girls can go to school in both districts, child marriage is still the norm. Many Yazidis have thrown away their much-needed identity cards because the government in Iraq insists the card is marked “Yazidi”; the moniker is an invitation to violence. These women want changes in the constitution and the laws for women and they want help from the international community to monitor those changes.

The wish list is long: a Truth Commission, a trial at the International Criminal Court to bring the perpetrators to justice, psychological help for the Yazidis and Christians who were the targets of Islamic State and assurance from the international community that this will never happen again—ever.

Correction: An earlier version of this story stated Canada has committed $1.1 billion to Iraq. The figure should read $1.6 billion over three years. Maclean’s regrets the error.