An Olympic miracle: Is Korean reunification in the cards?

On the eve of the Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, Allen Abel sets out across South Korea in search of a resolution to its decades-long estrangement from the North

A visitor uses binoculars to look towards the North Korean village of Gaepung-Gun at the Odusan Unification Observatory near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in Paju, South Korea, on Sunday, Feb. 7, 2016. North Korea launched a long-range rocket Sunday, just weeks after conducting a fourth nuclear test in the latest setback for international efforts to pressure the Kim Jong Un regime to end its weapons program. (SeongJoon Cho/Bloomberg/Getty Images)

Share

The good thing about visiting South Korea is that there’s no tipping, but the bad thing is that you’re never more than 10 minutes from thermonuclear obliteration. This is especially true at the Odusan Unification Observatory, a mountaintop aerie, museum and communal weeping platform located an hour and a half north of Seoul, overlooking the confluence of the Han and Imjin rivers and the communist paradise beyond.

From Odusan, it’s possible to look through powerful ’scopes to squint into the very lair of Kim Jong Un, the stubby little Stalin with plutonium in his veins whose greatest achievement as the supreme leader of North Korea may be that he is still the supreme leader of North Korea.

Given Rocket Man’s perverse predilection for creating long, tumescent missiles at the expense of food and freedom, it may be possible for the communists to eradicate Odusan in seconds before moving south to irradiate Seoul, followed by Samsung City, the Hyundai auto factories, the steel mills of Ulsan, the wriggling octopi of the Busan fish market, the old-lady abalone divers of Jeju Island and the shallow ski slopes and man-made snowflakes of Olympic PyeongChang.

Then: Tokyo, Guam, Honolulu, Disneyland, San Francisco, Seattle, Chicago, Washington, New York and the bibimbap palaces at Bloor and Christie in Toronto.

“Kim Jong Un is so young that he might do something stupid,” a man whose name tag reads K. S. Son is saying on the Odusan mountaintop, where he has worked as a security guard and museum guide for the past 26 years. “If that happens, I think we are safer up here. Especially if there is a chemical attack—the poison gas will stay down in the river valley.”

“Why would anyone choose to work for 26 years so close to the border of the Axis of Evil?” he is asked. Son Kee-su’s country has been in a technical state of war since the 52-year-old was born, and for a decade before that.

“I want to be here when our country is reunified,” Son answers. “Knowing that they don’t have food down there, or heat in the winter—that’s what breaks my heart.”

Many things brought us to the winter of 2018: the 516 Canadian soldiers who died to push Kim Il Sung and his Chinese Communist allies back from their shockwave blitzkrieg to the southern coast in the early 1950s; the tens of thousands of American and other United Nations troops who fell beside them, and the uncounted Korean and Chinese dead.

Then there were the decades of enticement and appeasement and taunting ridicule of the Kim dynasty by the West; the murderous repression of all dissent inside the country and its personality cults and one-channel radios and paranoid isolation from the wired world; not to mention the eagerness of the Red Chinese and the Soviets and, later, Vladimir Putin’s Russia to prop up an impoverished and insane puppet state on the Korean peninsula and to encourage it to strut its capacity for fissile mass murder while starving its own citizens.

All that led to short-track speed skating in PyeongChang and short-fused presidents in Pyongyang and Palm Beach, Fla., and the bereaved and ancient Koreans who come to cry at Odusan for their clans and for their country.

“From here, I can see the village where my father was born,” retired school principal Bae Heung-jun sighs, turning from the telescope, his eyes welling. “He escaped, but all of my relatives who were left there are dead now.”

“Can there be a happy ending for the two Koreas after 70 years apart?” Bae is asked, the central question of this reporter’s journey.

“There has to be,” he replies. “Myself, I think there will be. We need to make an effort. We are one race and there is lots of economic competition throughout the world. If we put our power together, we would be more competitive. People from North Korea know that, but they can’t speak up because they are stuck with the Kim family, and due to the strict government control.”

“I think we have a better chance of war, now that they have nuclear weapons,” reasons Son Kee-su, the guide. “These days, there are a lot of defectors and soldiers from the North coming to the South. I am suspicious of this trend. I think they are planning something.”

In trade for those few desperate soldiers who bravely sprint across the heavily militarized Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) while being shot at by their own brothers-in-arms, South Korea blasts K-Pop music northwards from the army base at Odusan, hoping to inspire a revolution.

(This may not be as far-fetched as it seems; in Moscow in 1998, this reporter asked a former high-ranking Soviet sports official, “When did you know that it was over?” He replied, “The first time we heard the Beatles.”)

“K-Pop could help,” Bae Heung-jun, the visitor, says. “People all over the world love K-Pop music. If there are DVDs that get passed around North Korea on the black market, our culture can unite the country.”

(The black market is a primary source of both sustenance and clandestine thumb-drives filled with soap operas from the booming South for millions of North Koreans. A decade ago, when factory workers at a short-lived joint-venture industrial park in the North were rewarded with Mae West-like Choco Pies, the pastries wound up being sold illicitly for the equivalent of a day’s wages.)

The men are asked if they trust U.S. President Donald Trump to keep them safe.

“In my personal opinion, Donald Trump is kind of suppressing South Korean power,” Son says. “He wants to control us. We need to control ourselves and our own future.”

The first time the Olympic Games came to South Korea, Canadians in the country enjoyed two days of joyous congratulation and free OB beer. It was 1988, a September to remember if there ever was one.

“Canada! Ben Johnson! High five!” the locals would clamour at anyone wearing a Maple Leaf. But you know how that sprinter’s story turned out.

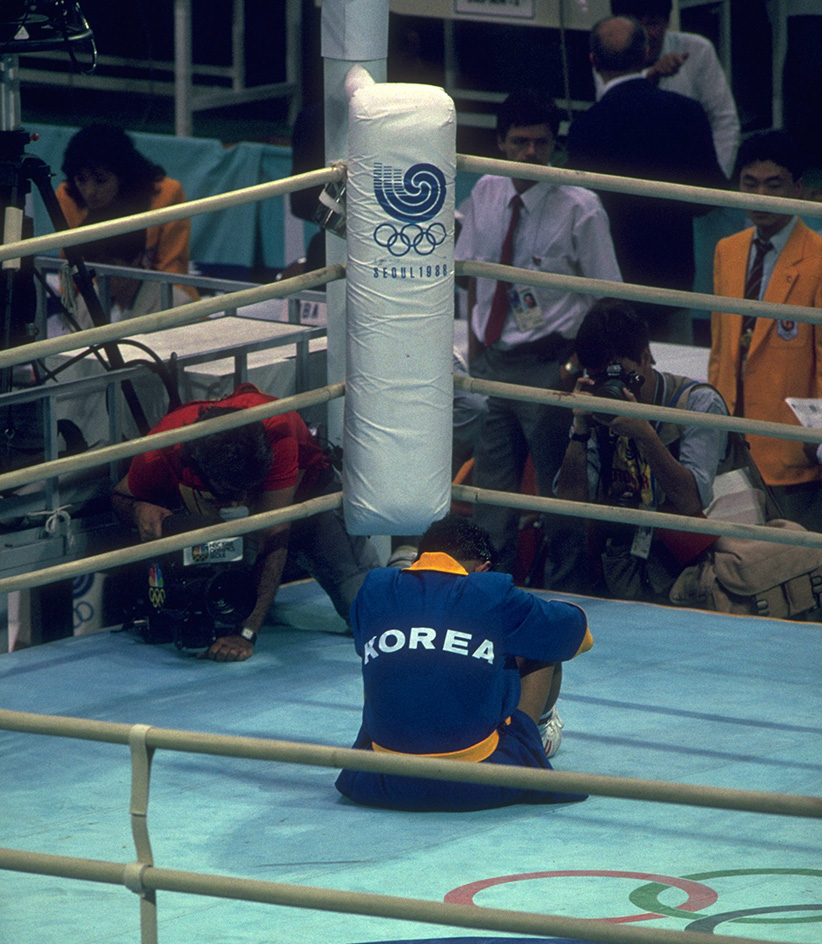

That same week, a young Korean boxer named Byun Jong-il—teased all his life because he shares his forename with the Dear Leader Kim Jong Il, the pot-bellied North Korean dictator who was Great Leader Kim Il Sung’s son and Kim Jong Un’s father—repeatedly head-butted his Bulgarian opponent, lost the fight on points, then sat down in the ring and refused to budge and cried for more than an hour, even after they turned the lights out and everybody went home.

Three decades later, we’re all 30 years older and Byun Jong-il—who went on to become the bantamweight champion of the world—is a successful businessman and TV commentator.

“Politics and the Olympics need to be separate,” he comments during a meeting at a fitness club he used to own. “But now, when I think back, there was too much politics involved. The Olympic Games is buried by politics. And this makes me sad.”

If anyone expected the Seoul Olympics to unify the peninsula, they were disappointed; North Korea didn’t even take part. As Byun recalls, South Korea wasn’t exactly a bastion of participatory democracy in those days either: “The country was ruled by the military regime. It was actually the peak time of conflict between the North and the South. I don’t see how the Olympic Games helped relations at all.”

Now Kim Jong Un has suddenly decided to send a handful of figure skaters and women’s hockey players to the five-ringed circus, and to allow them to march together with the southerners in the opening ceremony. He will also permit hundreds of cultural performers and “cheerleaders” to cross the DMZ without being shot, a masterstroke of gamesmanship that makes Little Rocket Man appear more presidential and conciliatory than America’s tweetstormer-in-chief. (The North staged the same telegenic gambit at the Olympic Games in Sydney in 2000 and at various Ping-Pong and youth soccer events in recent decades, with no lasting effect. The two Germanys fielded joint teams at several Olympic Games in the 1950s and ’60s, but the Berlin Wall did not crumble until 1989.) But with North Korean triple-Lutzers, folksingers and puck-chasers in PyeongChang, a first strike seems unlikely, at least until they cross back over.

“We are one race,” says Byun. “We have lived apart since after the war, 70 years ago. We are the only separate country in the world. Now I don’t know how long it will take, but we need to be unified. Like Germany, but not in the same way—not suddenly, but slowly and constantly. We need to change North Korea a bit and we need to help them, if we can. And North Korea has to give an inch as well. It will take time. I hope it happens in my generation.”

Washington interlude number one.

U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz, a Republican from Alberta, is discoursing on North Korea policy at the Hudson Institute on Pennsylvania Avenue.

With his characteristic humility, Cruz is enumerating the steps that he has single-handedly taken to neutralize what he calls “the mafia-like operation that is North Korea” and to, in his words, “stymie the march of this madman.”

Kim Jong Un, Cruz says, is “a megalomaniacal narcissist who desperately wants to stay in power” and “a few cards short of a full deck.” Speaking of which, from the room where Cruz is fulminating, it is possible to see the Trump International Hotel right across the street.

“I called for the immediate deployment of [anti-missile system] THAAD to South Korea,” Ted Cruz says.

And: “I laid out a comprehensive strategy.”

And: “I promoted relisting as a state sponsor of terrorism.”

There is much more, but space is limited.

“Its time for Kim Jong Un to worry about what we do,” Cruz says.

“What about the Olympic Winter Games?” someone in the audience asks.

“We need to avoid being distracted by shiny objects,” warns Cruz. “The South Koreans are in an incredibly difficult situation right now. They have a neighbour who’s nuts.”

Back to Korea.

Hundreds of young Canadians come to South Korea every year to teach English. Two of those are James Macdonald of Dutch Settlement, N.S., and Chantal Peppin of Oakville, Ont. They are found eggs-benedicting at Canucks, a Canadian-themed sports bar and restaurant near the giant, Seoul-sustaining U.S. military base in the Itaewon district of the capital, where a lonely expat can watch the Saturday doubleheader of Hockey Night in Canada on live TV while eating Sunday brunch.

The young graduates of St. Francis Xavier University are working in Gwangyang province, near the bottom of the peninsula and close to the largest steel factory in the world, not that Kim Jong Un would be interested in that sort of thing.

“My father seemed to think that there was a real chance that I’d get blown up,” Macdonald admits. “But the research that I did indicated that South Koreans aren’t afraid. And if they aren’t afraid, why should I be?”

“In Gwangyang, we’ll just wave at the rockets as they fly to Hawaii,” Peppin cheerily declaims.

“Nowadays, poutine is such an essential culture of Canadian life,” announces a sign at Canucks, near the autographed photographs of Michael J. Fox, Elisha Cuthbert, Justin Bieber and Jim Carrey, who signed his picture “Spank you very much.”

“We are not afraid of war,” says 19-year-old Dexter Jeon, scion of the Korean-Canadian family that owns the eatery. “But my grandparents in Vancouver, they are terrified.”

In 1999, a teenaged North Korean ice hockey player was told by her father that the entire family was going to try to escape to China. The Great Leader was dead, the father said, and the girl’s parents, who worked for the state security apparatus, were in unspecified jeopardy. Now was the time to cross the Yalu River, just as hundreds of thousands of Mao Zedong’s soldiers had forded it in the opposite direction during the Korean War so many years before.

The young woman, whose name is Hwangbo Young, went on to play for the South Korean national team and to become so famous here that a movie was made of her extraordinary life. Now she is standing in the grandstand of an arena in Seoul and tersely—based on her own experience—cutting through all the blue-sky hopefulness that these Games somehow might mark the beginning of the beginning of the beginning of the end of divided Korea.

“Sports is just sports,” she snaps. “Politicians keep using this for their own politics. But through this, peace or unification is impossible. The appearance of North Korea in our press or the international press is all fake news.”

Clearly she doesn’t feel there can be a happy ending for the two Koreas anytime soon.

“Not in my lifetime,” she declares. “The North is a communist dictatorship, and if that doesn’t change, we’ll be divided for 700 years.

“Kim Jong Un is a bad bastard,” Hwangbo continues. “Maybe money will buy him out.”

Does she trust Trump to protect South Koreans from their neighbour’s aggressions?

“I don’t trust anybody,” she replies.

A 43-year-old kindergarten teacher named Kim Mi-seong has brought her two young children to ski on the artificial powder of an alpine-style resort in Olympic PyeongChang. It’s winter break in the Land of the Morning Calm.

“Aren’t you afraid of nuclear attack?” she is asked.

“Really? That’s nonsense,” she replies. “We are here with our kids. And because the Olympics are here in PyeongChang, we brought our whole family here to have fun. There won’t be any danger here. If you look around, a lot of families have come together. Would I come here with my kids if it was dangerous?”

She’s skeptical whether the two Koreas can truly come together.

“We have to consider the cost of reunification,” she says. “We would have to support all the North Koreans for many years. It would cost us a lot of what we have built in the country. Why should we give what we have earned to them?”

Everything that Kim Mi-seong is saying is typical of her generation—whatever passion, longing, wistfulness or anguish was felt by her parents and grandparents is fading now, erased by distance and time.

“This younger generation, what they have seen is the South Korean government giving out aid, giving a lot of concessions, but North Korea betraying that trust,” says Ji-Young Lee, a professor at the School of International Service at American University in Washington, who has researched the attitudes of South Koreans. “They have become very skeptical. Those who are in their 20s have the lowest support for reunification. It’s actually across the board—the percentage of people who want reunification for the emotional reason that the two Koreas are the same ethnic group and the same nation—that percentage has gone down and down. And those who do want to see it happen have a much more practical reason—lessening the threat of war.”

Lee too isn’t certain whether reunification is in the cards—or perhaps just wishful thinking when the two sides are still so far apart.

“I worry about internal dynamics in North Korea that we don’t know a lot about,” she notes. “I’m very pessimistic because of the level of terror. Kim Jong Un has actually tightened the level of control.

“The question is, will his son be able to continue the kind of governance that his father and his grandfather and great-grandfather have done. The way they govern is working, but it is not sustainable. Of course, that’s what we were taught when I was a schoolkid.”

Washington interlude number two.

Henry Kissinger, 94, has been called to testify on the North Korean nuclear threat and other global endangerments before the Senate Armed Services Committee, but he is not the oldest witness at the dais.

He calls North Korea “the most immediate challenge to international peace and security.

“If North Korea possesses military nuclear capability in a finite time, the impact on the proliferation of nuclear weapons could be fundamental,” Kissinger continues.

Sitting next to Kissinger is former secretary of state George Shultz, who just turned 97. When his turn to speak comes, Mr. Shultz quotes the retired Episcopal bishop of San Francisco: “When you put your hand on the Bible and take the oath of office, you’re president of the United States. But when you put your hand on the nuclear button and you can kill a million people, you’re not the president anymore, you’re God.”

Back to Odusan and the broad, sad vista

of the sealed Kim-dom to the north.

Inside the museum are photos of the few tearful reunions that a handful of Korean families have been allowed these past 70 years, the heartbreaking letters and testimony of the long-divided, and a cardboard mock-up of a bullet train whose route is shown as Seoul-Pyongyang-Paris (may we all live long enough to ride it).

There is a real country across the border: people work, study, love, play, sing, scrounge, barter, whisper, endure, watch and read what they are permitted, and wonder—or perhaps they already know—what pleasures and treasures await them beyond Odusan, beyond the wire and the mines, and the price they would pay for trying to escape, or for succeeding.

We wander around the observatory, accompanied by a 30-year-old named Kang Yechan (everybody calls him Channy). We watch videos of sobbing old sisters embracing for the first time since they were schoolgirls. Yet Kang is unmoved.

Leaving the mournful pavilion, Channy looks out at the river and says, “It’s been too long to cry.”

Thirty years after he covered the Seoul Games for CBC TV, correspondent Allen Abel returned to report on a still-divided Korea as part of CBC’s coverage of the Winter Olympics opening ceremony.