How Canada’s child welfare system fails refugees like Abdoul Abdi

Opinion: Why government officials had a responsibility to seek Canadian citizenship for the Somali refugee

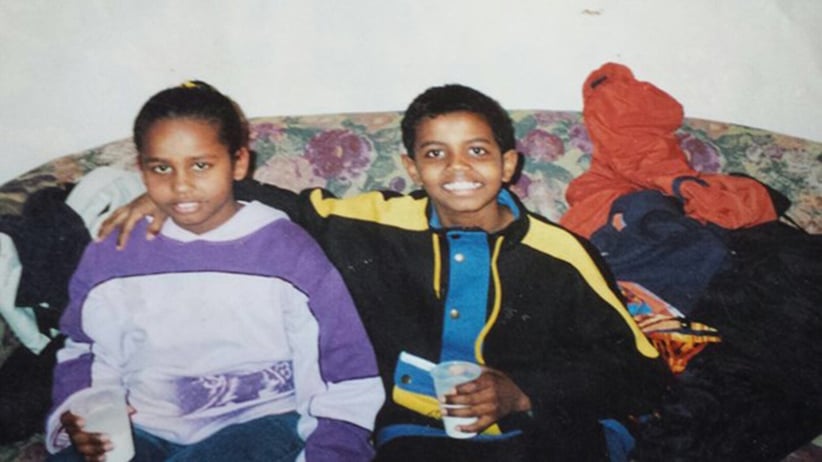

Right, Abdoul Abdi.

Share

Abdoul Abdi’s pending case has recently captured Canada’s attention. The 23-year-old came to Canada from Somalia at the age of six, along with his sister and aunts. He was soon placed in foster care by the Nova Scotia Department of Community Service. The reason he was taken from his family was never properly explained, but the government proceeded to move the young boy through 31 separate placements and failed for years to seek citizenship for him.

He now faces removal from the country. On Jan. 4, he was released from prison after serving four years for a number of convictions, including aggravated assault (In a significant understatement, the sentencing judge in 2014 acknowledged he had suffered “some misfortunes” since coming to Canada). But having served his time, he was immediately re-arrested by Canadian Border Services Agency due to his immigration status. He’s now being released again but his future in Canada remains uncertain. Advocates say this case demonstrates how government bodies with interlocking missions fail to connect, particularly the immigration and child welfare systems. Abdi doesn’t want his criminal charges expunged or ignored; he simply wants to face the same punishment as a Canadian with a similar record. Having lived here most of his life, under normal circumstances he most likely would have applied for—and earned—citizenship by now. But as a ward of the crown in Nova Scotia, the process never happened. And while this case has only recently caught the attention of Canadians, its underlying systemic failures are far too common. At the crux of Abdi’s request to stay in the country are the responsibilities of the child welfare system, says his lawyer Benjamin Perryman.

“In Mr. Abdi’s case, there appears to be no action taken in the first approximately four to five years that he was in care,” Perryman said in an interview. “Because of how complex even the citizenship process is, you need to get on it early, it is not something that can be quickly resolved. Child services has a responsibility to act diligently and take care of the children that are in their care. If the state is going to apprehend children, it has a responsibility to care for them. That includes non-citizen children.”

The child welfare world has slowly begun to deal with immigration, cultural and racial issues. The Peel Children’s Aid Society (CAS) in 2016 positioned itself as a leading expert among child welfare agencies to deal with thousands of Syrian refugee families arriving in Ontario. “Members of this team will assist other agencies across the province in navigating the complexity of the immigration and settlement systems, including reaching out to community, provincial, and federal partners,” stated a press release at the time. “Peel’s immigration team has extensive experience working with refugees and immigrants.”

The provincially funded initiative acknowledged the challenges faced by refugee families transitioning to life in Canada. “Parent–child conflicts and behavioural issues may occur. A child growing up in Canada is learning values and norms that differ from their parents’ more traditional values, and this can impact family relationships and stability,” Mary Beth Moellenkamp, the senior service manager at Peel CAS, said in the release.

MORE: How First Nations are fighting back against the foster care system

The Peel CAS acknowledged the connections between the immigration and child welfare system. Implicit within this project is an attempt to assimilate these children into Canadian society. A natural extension of this is ensuring children in the care of the state have the chance to become a citizen.

There is also work underway to take into account the unique needs of African Canadian children in care. The Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies undertook One Vision One Voice: Changing the Ontario Child Welfare System to Better Serve African Canadians (OVOV), an initiative focused on identifying the unexamined ideas and biases that contribute to the overrepresentation of African Canadian children in the system. The project is now forming committees to ensure practices recommended by OVOV—such as collecting data and establishing connections with the African Canadian community—are actually undertaken, says Kike Ojo, the project manager for OVOV. “It’s not good enough to have the document—the questions are on the implementation and what agencies are doing with this new information.” This kind of engagement could go a long way in cases like Abdi’s, especially if it includes addressing complex issues—like legal status—far earlier in the children’s lives.

In Nova Scotia, governmental officials argue that citizenship isn’t something that the state can foist upon a child in its care. Premier Stephen McNeil, while declining to specifically discuss the Abdi case, said he had asked officials to explore what options were being presented to children in care, but “it is up to those children as they grow into teenage years to decide whether or not they take advantage of those options.”

Noting the system failed Abdi multiple times, Perryman argues McNeil’s position is a dangerous one for the government to take. “The biggest thing a non-Canadian child in care needs is citizenship—it gives the right to have rights,” he says.

McNeil also ordered a review of the province’s handing complex cases that require intense support. This is undoubtedly good news, not just for Abdi, but for other children and youth that share the same circumstances. But as Robert Wright, the former executive director of Nova Scotia’s child and youth strategy, told the CBC: “You don’t solve the problem with the same brains that create it.” Asking bureaucrats to review their own system is a mistake. “My question [is] how are you going to substantially engage individuals who may be better able to understand the needs of a child like Abdoul Abdi to help solve this problem?” Wright said. “Let’s get some substantial external expertise in helping the province figure that problem out.”

In Canada, we have the evidence that Black children in care of the state need culturally appropriate and relevant support. The government needs to mandate measures to ensure children of the state, who already face challenges, are placed on a path to citizenship. Abdoul Abdi’s case further proves the validity and urgency in addressing child welfare issues in this country, with a culturally competent, compassionate and rational lens.

MORE ABOUT REFUGEES:

- Canada’s failing refugee system is leaving thousands in limbo

- As a refugee crisis unfolds, Central America needs Canada’s help

- Haitian asylum seekers are about to test Canada’s refugee system in a big way

- Government struggling to track impact of Syrian refugee resettlement, says auditor

- Migrants are dying in Canadian detention centres. The government needs to act.

- I made it out. But the war in Syria is not over.

- Ai Weiwei, an artist in exile, turns to the refugee crisis

- Alan Kurdi’s relatives on the Syrian conflict: “It’s going to get worse.”