Why a budding B.C.-Alberta trade war feels almost inevitable

Opinion: Alberta’s ban on B.C. wine is a declaration of war—and Canada’s political tradition suggests that’s where this is now headed

Share

On Tuesday morning, the vines west of the Rocky Mountains quietly met the grey British Columbia morning, as they often do. By the end of the day, the peace would be broken by the firing of the first salvo in what my colleague Stewart Prest called the War of the Rosés.

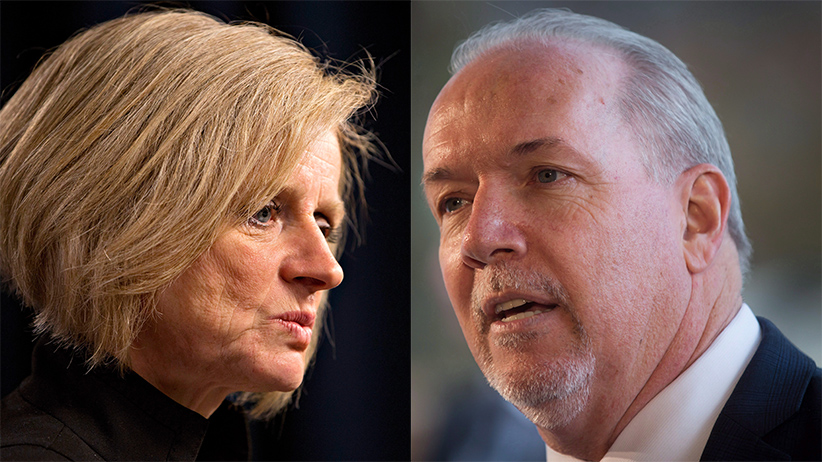

On Tuesday afternoon, Alberta’s NDP premier, Rachel Notley, announced that she was banning the import of B.C. wine to Alberta, under the authority of her province’s Gaming and Liquor Commission. The closing of the spigot is in response to the decision by neighbouring premier John Horgan—also a New Democrat—to consider limiting bitumen passing from Wildrose country into his province.

These are the sparks that might ignite a trade war. If that happens, the economic cost of the conflict could reach into the billions. Indeed, Alberta is considering further measures, including cutting the electricity trade between the provinces, and plenty of folks in B.C. have already suggested that the province stop importing beef from its neighbour to the east; Horgan himself has already hinted at the possibility. Meanwhile, according to Notley, this is a vine for a vine: “The cost of not going ahead with the Kinder Morgan pipeline is roughly $1.5 billion a year, just to Alberta trade.” A billion here, a billion there…

READ MORE: The war of mutual destruction begins between Alberta and B.C.

No one wins in a trade slugfest. In many cases, it will be workers and small business owners—many of whom live precariously to begin with—as well as consumers, who bear will the brunt of much of the fighting. But the governments of British Columbia and Alberta, as well as the federal government—which has tepidly joined Alberta’s side—now seem destined to do battle. Why? Because they have to be seen doing battle. Because it’s essential to them keeping their jobs. Because politics.

As strange is it may appear that two NDP governments are taking the boots to one another, with the feds forced to take sides, the whole thing makes a lot of sense. Politics is not merely—or even mostly—ideological. It’s first and foremost about winning and governing. And while politics may be a partisan affair, the interests of politicians will always be bound up with the interests of the polity they govern and the context in which that governing takes place. And it never hurts the governing party if they can whip up some sub-state nationalism in the process.

READ MORE: In B.C. and Alberta’s pipeline fight, only one side is unified

Alberta is oil-rich. It makes its money from exporting oil. Its workers are employed in the industry. Voters like a strong, stable economy and they love it when they can make, you know, a living. So, shocker: whichever party runs the province will be a pro-oil party.

In British Columbia, the NDP is hanging on to government by the skin of its orange teeth, backed by the Green Party, which is decisively anti-pipeline. During the spring election, Horgan hustled hard against Kinder Morgan, promising that if his party won, they would use every tool in the toolbox to stop the pipeline. While quite a few British Columbians support the pipeline, Horgan’s base and the voters he depends on to govern don’t—not to mention his Green Party partners.

For its part, the federal government has hitched its wagon to the national interest—just as you’d expect it to do. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has made it clear that as far as he’s concerned, the pipeline is good for the country. The project has been given National Energy Board approval. That makes sense. The Albertan oil industry is a major part of the country’s economic engine, and many Canadians are comfortable with the country building new pipeline capacity.

Perhaps you’ve heard the line that “Canada is a difficult country to govern.” The struggle over the Kinder Morgan pipeline is proof of that. Three governments across two jurisdictions are now caught in a race to the bottom that will harm workers, consumers, and quite possibly each other. Albertans go to the polls in May 2019. Several months later, in October of the same year, Canadians will vote in the 43rd federal election. No one can say for sure when the next B.C. election will be, given the precariousness of the legislature, but that’s plenty consistent with my point. Each party in each province and the country wants to govern and their jurisdictions nudge them in ways they have no choice but to respond to.

WATCH: Jagmeet Singh on the “biggest fight in the country”

So the warring will continue for now. And if in spite of what I’ve argued it seems like a head-scratcher—why all the fighting, which seems to serve no one while harming many?—recall that primates are one of the few, perhaps the only, species that engages in “altruistic punishment.” In his book Enlightenment 2.0, philosopher Joseph Heath reminds us that “We are willing to punish people who break the rules or act noncooperatively, even when it is personally costly to do so.” The same can be said of a province or a country: We will cut our noses right off to spite our faces, if we think the latter is giving us the nasty business. As irrational as that may sound, it comes from a long history of cooperation being necessary for survival. Indeed, in the case of Canada, cooperation in economic matters was a central reason for Confederation in the first place. (That, and not becoming American.)

On top of it all, the pipeline politicking is unfolding against the backdrop of a country that is struggling to live up to its climate commitments and address the greatest threat humankind has ever faced, amid global populist pressures, declining trust levels, and economic inequality and uncertainty. This moment is thus a reminder that politics is political, shaped by the moment and context in which governments and political parties operate. Moreover, it begs us to recall that our economic and political cycles, as well as the imaginations—or lack thereof—and the incentives they generate, remain too short and possibly insufficient to address the most serious and existentially threatening issues of our time.

But that’s how we do things. It’s enough to make you want to pour yourself a glass of wine.