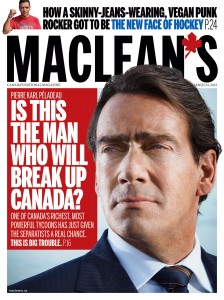

About that Pierre Karl Péladeau cover…

Martin Patriquin on what he got wrong about the PQ’s star candidate

Pierre Karl Peladeau

Share

About a week into the Quebec election campaign, I wrote the Maclean’s cover story about how the Parti Québécois’s recruitment of businessman and media mogul Pierre Karl Péladeau was a coup. Nabbing PKP to run as a candidate in the suburban riding of St-Jérôme, I wrote, “makes him (and the PQ) a contender in Saint-Jérôme and the neighbouring ring of suburban ridings around Montreal, home to large swaths of white, francophone conservative voters key to a PQ majority.” His arrival “was nothing short of a turn of events so spectacular it changes the dynamics of the entire campaign,” I wrote.

Ha! PKP’s entrance changed things, alright. But not in the way I thought. As we now know, PKP’s entrance into the race coincided with a quick and brutal slide in the polls, resulting in a historic loss for the Parti Québécois. Today, just over a month after I wrote that piece, the PQ is in shambles, its members and MNAs in a state of shock, and its leader Pauline Marois gone, having been turfed from her own seat.

Having won his own seat, PKP is now wreaking logistical and ideological havoc amongst party faithful. That part I got right, and it suggests the long-term marriage of the PKP and the Parti Québécois will be fraught, to say the least. Much of the rest I got wrong. Here’s why.

I misjudged the extent to which Quebecers have grown tired of referendum talk. Péladeau suffixed his 13-minute introductory speech with a declaration of his sovereignist credentials and a now-infamous fist bump. That bit merited exactly one line in my piece, but its significance deserved far more critical analysis. When I travelled to Quebec City in the week following the publication of the piece, nearly everyone I spoke with was completely turned off PKP, if only because of his sovereignist bon mots. Given PKP’s government-assisted largesse in procuring a hockey arena and the spectre of an NHL franchise, this should have made PKP a hero.

Instead, people only saw a return to the bad old days of referendum talk in his words. “I’m so disappointed in the guy it’s ridiculous,” insurance broker and hockey-mad radio DJ Mario Roy told me. “You want to go into politics to fix public finances and put things in order? Fine. But to pump your fist and say you want a country? Tabarnac.”

Now, Quebec City is an anomaly, in that it’s quite conservative and more pro-Canada than you’d expect. Yet as last week’s election results suggested, Roy’s sentiment echoed across the province: people are sick of separation and the 40-year chat over the machinations of separatism. PKP’s wee fist bump came to represent all of that, and the PQ was punished accordingly. Yes, Péladeau won his seat. But much of Montreal’s north shore stayed in the hands of the Coalition Avenir Québec.

I further misjudged the fragility of Pauline Marois’s image makeover. Marois had an image problem. She was seen as haughty, bourgeoisie and out of touch. She managed to reverse this, in part through her handling of the Lac-Mégantic tragedy in the summer of 2013 and the introduction of the so-called Quebec values charter in the fall. By January, her poll numbers were comparatively boffo, so much so that PQ handlers saw fit to have Marois front and centre in campaign ads.

All of that quickly went to seed during the election. For some inexplicable reason, Marois’s handlers didn’t have a set of talking points ready in the wake of Péladeau’s declaration. She didn’t have an answer to the inevitable question: when would a PQ government hold a referendum? Instead, she went on a weird tangent about open borders and a shared currency with Canada, then spent the next few weeks avoiding the question altogether. The Quebec values charter, meanwhile, wasn’t the elixir it was during the months before the election campaign.

I’m not sure PKP’s arrival caused Marois’s electoral descent. The questions surrounding the what, when and how of a possible referendum resulting from his fist pump would have inevitably come about at some point. Indeed, for the Parti Québécois, they always do—and, as the campaign demonstrated, they have a Kryptonite-like effect on the party’s electability. Like the PQ itself, I should have considered this a bit more before taking the plunge.