How Ottawa’s ‘Wanted’ list jeopardized deportation hopes

A high-profile arrest put one man in the spotlight, and now he risks torture back home—which means Canada can’t remove him

Share

By his own admission, Arshad Muhammad is a successful liar. A Sunni Muslim from Pakistan, he used a fake Italian passport to fly into Canada and file a refugee application. When his asylum claim was refused (because of his alleged membership in a terrorist organization), he assured the federal government he would go home—only to flee Montreal for Toronto and disappear. And, while living on the lam over the next eight years, Muhammad managed to elude authorities by working cash-only construction jobs and using yet another bogus name to register his cellphone. On paper, at least, he no longer existed.

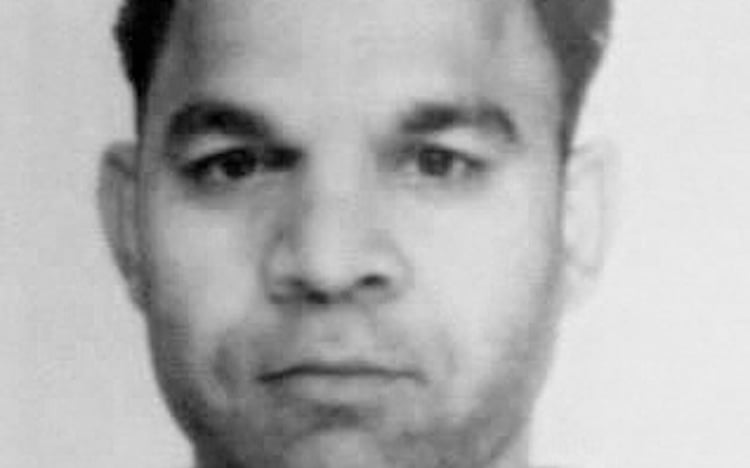

Today, the 45-year-old is behind bars for one reason: a “Most Wanted” website launched in July 2011 by the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), featuring the names and mug shots of 30 suspected war criminals who vanished before Ottawa could deport them. Muhammad was among the first fugitives busted by the list, arrested just one day after his blurry photo appeared online. (He was shopping at a tile store in the Toronto suburb of Mississauga, Ont., ordering supplies for a bathroom renovation, when an off-duty police officer recognized his face.)

At a press conference the next day, then-immigration minister Jason Kenney celebrated the arrest—more proof, he said, that the controversial website worked. Within weeks, the Harper government expanded the headline-friendly initiative to include other non-citizen fugitives (including dangerous foreigners ordered out because they committed crimes in Canada), and, at last count, more than 40 wanted people have been found and expelled, thanks to tips from the public.

Yet, 2½ years after his cover was blown, Muhammad is still here—threatening, from his jail cell, to strike a major legal blow to the same program that flushed him out of hiding. His latest Federal Court case, now in the hands of a judge, accuses government officials of improperly meddling with his file in a desperate attempt to save the Conservatives’ new program from an embarrassing scenario: that Muhammad would be allowed to stay in Canada because the feds posted his picture for the world to see.

At the heart of his court battle is a question that worried bureaucrats even before the list went live: By finally identifying its most wanted, did the government actually jeopardize its chances of deporting some of them? Except under extraordinary circumstances, Canadian law prohibits Ottawa from removing illegal residents who could face cruel and unusual punishment back home—and, after Muhammad’s high-profile arrest, an immigration officer found he would indeed be at risk if returned to Pakistan, where terrorists (real or accused) are routinely tortured.

That report, completed in October 2011, triggered a flurry of emails between staff at the Canada Border Services Agency, eventually leading to an unprecedented meeting between a director-general at CBSA and her counterpart at Citizenship and Immigration. In court documents, Muhammad’s lawyers have painted the meeting with a sinister brush, calling it a clear attempt by CBSA to pressure Immigration to overturn the report because it represented such a potentially devastating setback for the Wanted list. The website, of course, was designed to help find and deport the men in the mug shots—not create a loophole that would allow them to stay.

Despite all the arrests—and all the self-congratulatory press releases trumpeting each one—the Wanted web page has endured a difficult few months. In December, the federal privacy commissioner scolded Ottawa for its “potentially misleading” use of the term “war criminal,” considering that none of the men on the site has ever been charged with a war crime, let alone been convicted. (They were declared inadmissible to Canada, under a much lower burden of proof, by the Immigration and Refugee Board.) A few weeks later, Maclean’s managed to track down one of the missing men, calling into question just how hard authorities are searching for them. Asked why the magazine had little trouble finding Dragan Djuric when the agency couldn’t, CBSA responded by promptly removing his photo from the site and saying it couldn’t “comment any further on its operations.”

But Muhammad’s case could prove the most damaging development yet. His lawyers are alleging an “abuse of process” and requesting an indefinite stay of removal, which would allow him to remain in Canada after all. A ruling is expected any day. “Regardless of whether we win or lose, what the case shows, more than anything, is the extent to which they tried to protect the ‘Most Wanted’ program at the expense of fairness and the rule of the law,” says Lorne Waldman, his lead lawyer. “The story speaks for itself.”

When Muhammad first arrived in Canada in 1999 (armed with his fake passport), he told authorities he was connected to an Islamist group responsible for terrorist attacks in Pakistan, an admission that ultimately doomed his asylum claim. He now insists he lied about his links to the organization because an agent advised him to, promising it would bolster his chances of staying. (The name of the terror group is protected by a publication ban.) Whatever the truth, those details were not mentioned on the Wanted page; like all the fugitives, Muhammad’s profile included only his photo, date of birth, home country and last known city.

But, at that press conference after his capture, Jason Kenney disclosed Muhammad’s ties to Islamic terrorists and, when Pakistani media picked up the story, Muhammad claims his family in Faisalabad received repeated death threats. Still in custody pending his deportation, he then applied for a so-called Pre-Removal Risk Assessment (PRRA), arguing that his new-found notoriety—compliments of the federal government—put him in severe danger. (Again, Canada does not typically remove people to countries where they could face cruel or unusual punishment.)

Although the border agency is in charge of enforcement, it’s the immigration department that conducts the risk assessments. The first step in the process is an “opinion” rendered by an immigration officer. In Muhammad’s case, the officer sided with him, concluding that the two labels now attached to his name—war criminal and terrorist—make it “more likely than not” he would be treated harshly by Pakistani authorities.

At the time, Glenda Lavergne was director general of border operations for CBSA. Told of the finding via email on Oct. 13, 2011, she replied: “This one is not going well?.?.?.”

An officer’s opinion is not the final verdict; another immigration official (a minister’s delegate) considers the opinion and makes the ultimate decision. But Lavergne was concerned enough about “the quality” of the initial opinion to convene a meeting with the delegate’s boss, the director general of Citizenship and Immigration’s case management branch. In a sworn affidavit, Lavergne insists she had no “intention to influence the process in any way,” but other border services employees have criticized the optics of the February 2012 meeting—especially since the delegate had yet to render her decision.

Reg Williams, now retired, was director of the CBSA’s Greater Toronto Enforcement Centre when Muhammad was apprehended. In his own sworn affidavit, he says he was “taken aback” when he first learned of the “ill-advised” meeting. “I had never heard of of?cials at CBSA meeting with CIC to discuss a specific case when the [risk assessment] decision by the minister’s delegate in question was still pending,” he wrote. “At the time, I believed these meetings to be inappropriate, and I believe that to be true to this day.”

Another agency director provided even more damning testimony. Cross-examined about the meeting, Susan Kramer said Lavergne specifically told her Immigration counterpart, Michel Dupuis, that a positive risk assessment “could have a serious impact” on the Wanted list, including the prospect it “could no longer be used.” Kramer also described the meeting as “odd,” saying she would never have organized it herself. “If you want an independent decision,” she testified, “then I think we need to be careful not to give the impression that it’s not independent.”

Amazingly, Kramer also said she felt “comfortable,” after the meeting, that CBSA would receive the ruling it wanted. “It’s hard for me to explain it,” she testified. “It’s because we don’t normally meet with an independent decision-maker ahead of the decision, and I guess that particular action left me feeling confident. It would be something like if the litigator’s boss went and talked to the Chief Justice of the Federal Court. I can’t imagine the litigator not feeling somewhat confident from that action.”

In the end, CBSA did receive the decision it desired. Two weeks after the meeting, a minister’s delegate overruled the preliminary opinion, concluding that Muhammad is “unlikely” to be tortured if deported. Although that finding was later declared “unreasonable and contradictory” by a Federal Court judge, a second delegate assigned to reassess the file reached the same conclusion as the ?rst: Muhammad’s removal should go ahead.

It was only last May—when Muhammad’s lawyers first learned about the now-infamous meeting—that they filed yet another appeal in Federal Court.

In their submissions, government lawyers insist that no one from the Canada Border Services Agency attempted to in?uence Muhammad’s risk assessment and, even if they did try, there is no evidence they succeeded. As Dupuis from Immigration testified, he allows the minister’s delegates under his authority to reach their own conclusions. He doesn’t discuss their cases with them, and neither delegate had any knowledge of the February 2012 meeting, or CBSA’s worries about how Muhammad’s case could affect the Wanted list. “The substance of the meeting itself should not be given the nefarious characterization attributed to it by the applicant,” government lawyers wrote. “Ms. Lavergne, having concerns with the risk opinion, merely expressed her concerns to Mr. Dupuis.”

But even that, Muhammad’s lawyer argues, constitutes “direct interference in the decision-making process” and “an abuse of process that would bring the administration of justice into disrepute.” The overriding goal, Waldman charges, was to save the government’s new pet project from negative publicity. “To interfere in the decision-making process in a situation where the issue at stake was the risk of torture faced by the applicant because of ‘political’ concerns is clearly an improper motivation” and “calls for the most serious sanction from the Court,” he wrote.

If a judge agrees, Muhammad’s removal will certainly be postponed—again. In the best-case scenario, he will be released from his Toronto detention cell and stuck in immigration limbo for years to come: ordered deported, but illegal to deport.

He may complete that bathroom renovation after all.