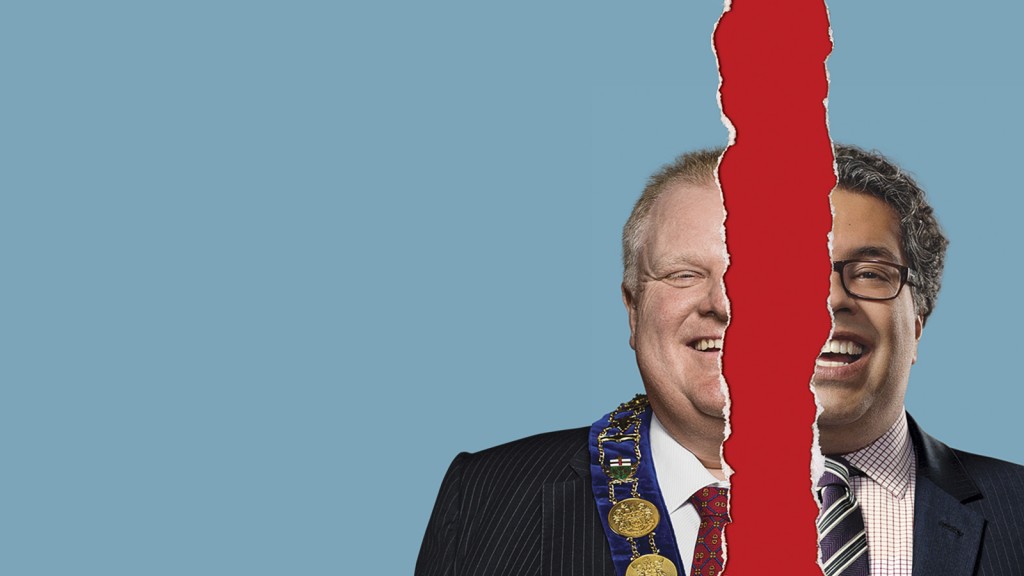

How the great Ford divide could come to a city near you

Rob Ford won on a wave of suburban voter discontent, and those voters are still angry—as are people just like them, in cities across Canada

Share

Douglas Ford Sr. was a provincial politician who bestowed considerable gifts—a thriving label company, burning ambition—on his politically minded sons. A sonorous voice, alas, was not one of them. When agitated, both Rob Ford and Doug Jr. can sound like circular saws biting into knotty pine, as Doug did last week when his chief rival in Toronto’s mayoral race, John Tory, tweaked him during a public debate. Determined to portray himself as a man of the people, the well-monied Tory boasted that he regularly rides the city’s crowded subways. Then, in a cheap but effective piece of theatre, he drew a transit token from his pocket and offered it to Ford. “I don’t want you to feel left out.”

Ford rendered his answer in an ear-splitting whine: “The only reason he took the subway was that his chauffeur was on vacation!” shouted the 49-year-old councillor, face colouring. So high was his timbre that he could be heard over the hoots of partisans gathered for the event at a downtown college campus. It reinforced an impression Tory’s team has worked diligently to sow: Doug Ford is angry; his campaign is on its last legs.

For much of the campaign, Torontonians seemed pleased by that thought. Having ridden the psychic rollercoaster of the past four years—from the crack-video revelations to sobering news that the mayor is battling a virulent form of cancer—more than six out of 10 were telling pollsters that under no circumstances would they vote for him. Even after Doug, generally seen as the stabilizing force in the family, replaced his brother on the ballot Sept. 12, Tory enjoyed a commanding 14-point lead in the polls. Then, last week, a survey conducted by Forum Research suggested that Ford had all but erased that gap, garnering 37 per cent support to Tory’s 39. Suddenly, improbably, the race was back on.

Related reading:

- Ivor Tossell on fear and loathing, cynicism and untruths, on the road to city hall

- Why Doug Ford can’t win

- What do we know about Doug Ford?

- Five questions about the Ford swap

The poll could be an outlier; it could signal a watershed moment in the campaign. For the rest of Canada, it means the schadenfreude moment it’s been enjoying at Toronto’s expense is not yet over. Faced with a candidate in Tory whose wealth, polish and cosmopolitanism encapsulates the city’s self-image, a surprising number of voters still lean toward the angry man with the grating voice—undeterred by the legacy of scandal, bickering and global ridicule he and his brother have brought on their town. To someone watching from afar in Vancouver, Calgary or Montreal, it invites an obvious question: Have Torontonians learned nothing from the past four years?

In fact, they’ve learned lessons the rest of the country would do well to heed. Rob Ford exploited suburban anger in the city when he stormed to victory in 2010, but underlying that discontent were forces now operating in cities across the country. Toronto’s unique political landscape merely provided a stage for those forces to play out in all their operatic glory.

Consider, for a moment, the city’s image as seen on picture postcards—a shining metropolis perched on the shores of an azure lake. That city is still there, but with its forced amalgamation of municipalities in 1998, the provincial goverment has bolted it to a semicircle of communities—Etobicoke, North York and Scarborough—that once defined Canada’s suburban middle class. The idea was to formalize Toronto as the economically integrated “megacity” outsiders imagined it to be. But amalgamation took place during a period of wrenching social and economic change. Manufacturing jobs that had fuelled the suburban middle class were disappearing overseas. At the same time, the professionals, creators and executives who defined the new economy were flooding into the once-tatty downtown, driving up property prices and driving lower-income immigrants into the declining suburbs. The city was turning inside out.

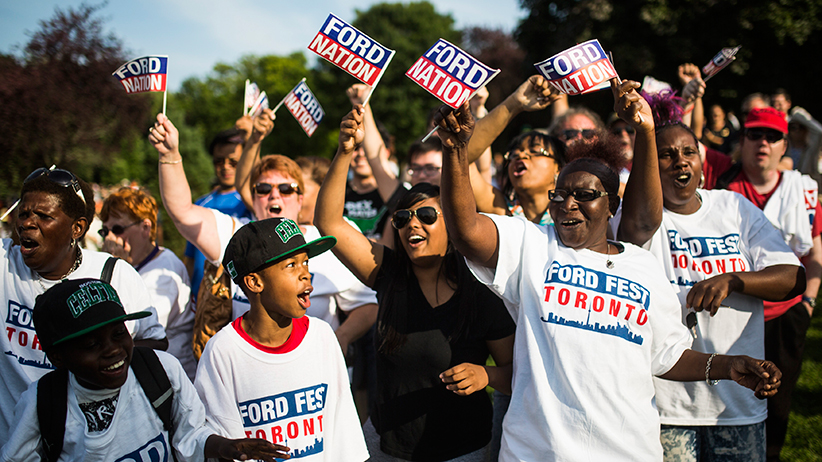

The fault lines had started to appear in past mayoral elections, but it took Rob Ford’s candidacy to fully reveal the schism. Suburban voters were galvanized in 2010 by the unabashed anti-elitism in his messaging. (Who but a fat cat, after all, would ride the “gravy train”?) Their activation overturned long-held assumptions about who turns out for municipal elections. More than half the residents in districts that voted Ford were first-generation immigrants; less than 30 per cent had gone to university and their average household incomes were 25 per cent lower than those in areas that swung to Ford’s closest opponent, George Smitherman. In the once-autonomous suburbs, Ford received more than double Smitherman’s vote take.

To Martin Horak, a Western University political scientist, this result speaks to one of the most important, and least understood, dynamics in Canadian urban politics. With deindustrialization has come growing economic disparity, he says, and nowhere are the extremes more stark than in the country’s big cities, where hostility between centres and suburbs is on the rise. Horak points to Ford’s 2010 voting base as a combination of young, blue-collar workers and older people who grow steadily more angry as they watch their standard of living decline. “Maybe they’ve been laid off, maybe they’ve had to retrain or maybe they’ve retired on limited incomes,” he says. “They’re mad and they’re frustrated, and the importation of this new and expansive local government has made them feel really left out.”

You can see the dichotomy on income maps. Since 1970, the proportion of middle-income neighbourhoods within Toronto has fallen from 66 per cent to just 29 per cent, according to the Neighbourhood Change Research Partnership, an urban economics initiative co-ordinated by the Cities Centre at University of Toronto. High-income neighbourhoods, meanwhile, have risen to represent 19 per cent of the city, up from 15, while low-income areas ballooned from a fifth of the city’s neighbourhoods to just over half. The vast majority of the latter popped up in the ring of suburbs where Ford garnered the most votes.

It’s by no means a Toronto-only phenomenon. The Cities Centre has charted similar patterns of disparity in Halifax, Montreal, Winnipeg and Calgary, noting wealthy and low-income residents increasingly “self-sort” into separate parts of their cities. In Vancouver, the share of high-income neighbourhoods doubled between 1970 and 2005, to 32 per cent, with dramatic concentration of wealth in its downtown core. “You see new, expensive houses and condos creeping into more and more areas of Vancouver,” says David Ley, a University of British Columbia geographer who studied the region for the Cities Centre. Low-income people, meanwhile, have been driven to surrounding municipalities like Surrey, Langley and Coquitlam, where Ley says leaders “have been slow to take ownership of the poverty showing up in their midst.”

How this shift plays out politically depends on the city, because the governance structures in each vary. Vancouver, for instance, has not amalgamated with its surrounding communities, but deals with them through a regional council of mayors. Montreal amalgamated in 2002, then partly demerged four years later. But there’s no denying the cultural gap between urbane, cosmopolitan city centres and outlying communities. In Toronto, downtowners advocate for bike paths, social housing and urban rapid transit, while suburbanites chafe against the taxes and fees levied to pay for them. In Montreal, the debate over the PQ government’s proposed charter of values, with its ban on religious wear in public institutions, pitted the island of Montreal—home to 80 per cent of the province’s immigrants—against surrounding towns and bedroom communities. Vancouver’s soaring real estate market, meanwhile, has given rise to a well-organized “anti-gentrification” movement aimed at trying to slow, if not halt, the forces pushing all but the wealthy out of the downtown. That the movement now seeks to shield from development the city’s Downtown Eastside—one of the country’s seediest neighbourhoods—tells you just how far the ground has shifted.

What, then, can an urban leader do to ease these tensions? Not much, admits John Duffy, a Liberal political strategist currently working on Tory’s mayoralty campaign. The economic forces transforming Canada—free trade, globalization, technology—lie largely beyond their reach. That, says Duffy, has opened the way for municipal politicians to “harness the sense of bitter alienation” that comes from having so much taken away. “The people in these areas have lost so much,” he says, “yet at the same time they must look at the gathering prosperity in the go-go parts of the urban economy. Their sense that something unfair is happening is palpable.”

That summation wouldn’t seem half so bleak if leaders at higher levels were addressing the issue. Instead, everyone from central bankers to G20 leaders have stood by as wealth and income gaps have widened throughout the developed world. Here, the richest 10 per cent of Canadians have seen their median net worth grow by 42 per cent since 2005, Statistics Canada figures show. They now sit on nearly 48 per cent of the nation’s wealth while poorest 50 per cent hold just five per cent.

It probably doesn’t help that the country’s political leadership skews discernibly these days to cosmopolitan sophisticates of all political stripe. To the left of centre are Calgary Mayor Naheed Nenshi, his Edmonton counterpart, Don Iveson, and Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne. To the right are Jim Prentice, the newly installed premier of Alberta and, if he wins, John Tory. None would cop to downtown-centrism, and all show varying degrees of empathy for those the new economy has left behind. But none can claim to be an authentic voice of the suburban working class the way the Fords can.

That Fords do it so well is an irony that never stops nettling left-leaning Torontonians. Rob and Doug, goes the complaint, grew up in an upscale grove of Etobicoke never wanting for money. The Fords’ anti-tax, cost-cutting platform arguably stands to harm the interests of low-income suburbanites by choking off cash for better regional transit and affordable housing. Yet they’ve made strengths of the biggest campaign issues by framing them as matters of fairness, demanding full-service subways in the suburbs, even though experts say above-ground light transit is better suited to less densely populated areas. “I believe in fair transit—subways across the city,” Doug Ford said defiantly at last week’s debate. “I will make a fair and equitable underground transit system.”

Put simply, the Fords grasp how a workaday suburbanite might think, viability be damned. They know, for instance, that a two per cent property tax hike is felt more keenly by someone scrambling to pay a $300,000 mortgage than someone comfortably carrying a $700,000 one, so no matter how cash-strapped the city grows, they oppose tax hikes. They know, too, that their support base commutes by car, so while the rest of city hall obsesses over the proper size of sidewalk patios, or the need for rooftop gardens, they decry traffic-choking thoroughfares in Etobicoke and Scarborough.

All of it serves a narrative rooted in class-based identity: Not only are the downtowners in expensive clothes out to screw you, but they’re all part of the same team. Earlier in the year, when the city’s police chief, Bill Blair, responded angrily to rude remarks a drunken Rob Ford had made about him, Doug suggested Blair was part of a conspiracy to get John Tory elected. And at last week’s debate, Doug repeatedly prefaced rebuttals with the phrase “I’m the only one at this table” (e.g. “I’m the only one at this table who can say he’s actually inside [public housing] every week”). The effect was to cast his opponents, Tory and Olivia Chow, as part of the same elite consensus. In truth, they’re in much different ideological camps.

Here, then, lies one legacy of the Ford era, whether or not Doug wins: a destructive brand of politics that has left some to ponder structural reforms—if not to quell demagoguery, then at least to keep civic business on the rails. Horak, the political scientist at Western, points to Vancouver, where municipal political parties help build consensus, while serving as a kind of filter for policies and candidates. “If we had a well-established party system in Toronto,” he says, “it’s pretty likely that Rob Ford’s political party would have replaced him [as leader].”

If nothing else, the rise of the Fords should alert the rest of the country to the sub-surface currents roiling beneath its cities. While Rob Ford’s mayoralty ultimately imploded in the face of his personal problems, the animus that brought it to life remains strong, say observers. More important, the way to exploit it is now in plain view. “Imagine a Rob Ford without the personal problems who makes the same promises, saying the same things again and again,” says Renan Levine, a political science professor at University of Toronto’s Scarborough campus. “That campaign strategy will be emulated by other ambitious politicians.” Horak goes a step further. “The Ford phenomenon shows us the extent to which Toronto and, I’d say, other Canadian cities are internally divided,” he says. “You can’t just wish it away, or even restructure it away. In any new structure you set up, a new Rob Ford is going to emerge.”