Welcome to British Columbia, where you ‘pay to play’

B.C. has become a Wild West of political donations. Critics worry it’s slowly eroding public confidence.

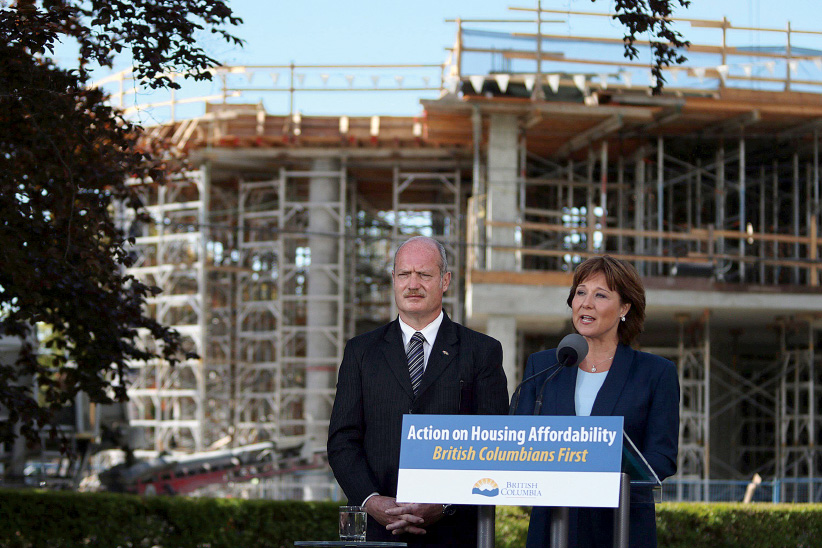

Wearing a hard hat, B.C. Premier Christy Clark listens to a question at the Woodfibre LNG project site near Squamish, B.C., on Friday November 4, 2016. (Darryl Dyck/CP)

Share

Last year, the British Columbia Liberal Party raised more money than any ruling party in any other province in the country. It pulled in 13 times more than the Quebec Liberal Party, six times more than the Alberta NDP, twice what the Liberals did in Ontario. That’s a province with three times B.C.’s population, an economy triple the size, and a head-office count quadruple that of the Western province. And all this was before Ontario brought in sweeping reforms ending corporate and union donations, dropping the ceiling on annual individual donations and banning cash-for-access fundraisers.

Bananas, right? Now consider that in the three years since Christy Clark’s majority win, the Liberals have added some $32.5 million to their war chest. In the first 12 days of January alone, they took in almost half a million dollars in contributions, approaching what Manitoba’s ruling NDP did in all of 2015 in the run-up to that province’s last election. And consider that in the 10 years leading up to 2015, the B.C. Liberal Party took in $3.1 million from Alberta oil and gas firms, almost twice as much money as that province’s governing party at the time, the Progressive Conservatives.

British Columbians’ faith in democracy is being undermined by the vast sums flooding the system, and there’s a growing concern that their government is essentially being bought and paid for by a wealthy clique. And with figures like those above, it’s getting hard to argue against the idea that democracy in B.C. has devolved to which party can amass the biggest pile of dough.

B.C. political fundraising is a free-for-all. Parties can accept any amount of money, property or services from any corporation, union or person living anywhere in the world. The single limit to this frenzied giving: charities are barred from donating.

This puts B.C. in a unique position. Most of the developed world, and some of the planet’s most corrupt nations, including Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Kenya and Russia, set ceilings on party donations, according to data compiled by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, based in Stockholm, Sweden. All of North America, all of Eastern Europe and the entire Arab world except Lebanon and Iraq bar donations like the $30,000-to-$50,000 ones the B.C. Liberal party has received in recent years from foreign donors.

It’s so bad that the New York Times last month went to B.C. to write a scathing piece on the Clark government’s “unabashedly cozy relationship between private interests and government officials.” Deputy Premier Rich Coleman said he found the reporting “laughable.” Outside Liberal ranks, few found it funny.

It is not known how much the B.C. Liberal Party has pulled in from outside Canada. But Dermod Travis of IntegrityBC has compiled a list that he calls the “$100,000 club.” It has 177 members, including developers, mining companies and energy firms that have fed the party some $55.7 million in the past decade.

Critics have pointed out that B.C.’s conflict of interest commissioner Paul Fraser—whose son is a long-time friend of Clark’s and sits on her executive council, as a deputy minister*—has never, in nine years, found the Clark government in violation of B.C.’s conflict of interest legislation. (The law firm where Fraser worked made donations to the Liberals, though Fraser has stated, “I did not attend any of these [fundraising] events, nor was I part of any discussion concerning [the firm’s] contributions.”)

Critics similarly point to contributions by large companies like Ecotex Healthcare Linen Service ($115,000 donated to the Liberal party since 2005), Emil Anderson Construction ($50,000), Kinder Morgan and its industry supporters ($719,000) and Imperial Metals and its subsidiaries ($195,000). Those same companies have, respectively, received a 20-year government laundry contract, a $36-million six-lane highway expansion contract, Clark’s approval for a controversial pipeline and a permit to open a new mine. In the case of the mine approval, it came one year after Imperial Metal’s controlling shareholder, N. Murray Edwards, hosted a $1-million fundraiser for Clark in Calgary. There is no suggestion of nefarious activity in any of these cases. But critics say the mere appearance of conflict is worrisome.

None of it is up to the public to litigate. It is, however, up to government to adopt regulations, legislation and practices that prevent even the whiff of conflict of interest from sullying B.C.’s global reputation.

“The only people not embarrassed by any of this are Christy Clark and the ruling Liberals,” B.C. NDP Leader John Horgan told Maclean’s. “There is nothing funny about giving donors and loyalists a billion-dollar tax cut while making regular people pay for it with higher bills for car insurance, electricity and health care. There’s nothing funny about a ruling party raking in millions from developers while watching housing prices soar out of reach, without lifting a finger to help. Politics is about trying to make things better. This is embarrassing. I’m certainly not laughing.”

In response to a request for comment from Clark, the premier’s office pointed to recent comments she made in late January about her government’s fundraising activities. “I think really there are only two ways to fund political parties. And if political parties can’t fundraise in the private sector, the money comes from taxpayers. And I don’t think taxpayers want that.” Clark’s office also pointed to the NDP’s own fundraising activities, including a recent event featuring Horgan to discuss the finance and credit union sectors, for which tickets ranged from $250 up to $10,000 for a “gold sponsor.” “If I have someone who wants to sit down and talk to me and they want to give me 50 grand,” Horgan told the Globe and Mail last year, “I’ll take that.”

The mudslinging shows how badly rules are needed, regardless of which party is in power.

B.C.’s financing free-for-all is perfectly mirrored by its ballooning lobbying industry. Few rules or regulations govern it, either. Competition is tight: 3,014 lobbyists and organizations fought for access in B.C. this year, 1,195 more than even Ontario.

Unlike Ontario, however, lobbyists in B.C. can shower almost anyone except an MLA with gifts and benefits of any value, as often as they want. They can use false and misleading information in pleading their case. They don’t have to declare when they’re lobbying: the sales jobs can be couched as a friendly chat between old pals. And all but ministers, who are subject to a 12-month cooling-off period, can do it the second they quit their job as a public office holder. B.C.’s lobbying watchdog has urged the Clark government to adopt regulations that would limit all of the above. Last summer, when Elizabeth Denham stepped down from the role, she made it her “parting wish.”

At this point, “there is no daylight between government relations roles at B.C.’s biggest companies and the premier’s office,” one lobbyist based outside the province told Maclean’s, speaking anonymously, given concerns of professional retribution. “That line has been completely erased. That is literally their social network. They go to each other’s cottages. They take trips together,” he adds, describing raucous dinners he has attended with Clark’s staff and a group of select lobbyists. The mix of warmth and competitiveness has fostered an unusual and deeply unhealthy intimacy. “No one is breaking any rules or laws or doing anything criminal,” the lobbyist is quick to add. “B.C. has no rules, so everything goes. It’s like the Wild West: only the fittest survive.”

Infinite leniency and infinite money make for a toxic mix. “I have to tell my bosses, ‘In B.C., you have to pay to play.’ ” If your client doesn’t donate, it puts you at a competitive disadvantage, he adds. It’s a small province, after all; the Liberals know exactly who is funding them, the lobbyist notes, magnifying the role donors play and the access they receive in return.

This gets to the root of the problem: the huge amount of money soaking the system, he says . “The only way to fix it is by taking money out.” If changes don’t come soon, he adds, “British Columbians will lose all faith in their politicians.”

In response to increasingly loud concerns over political financing, the Liberals often point to “real-time disclosure,” which the party deemed a radical new approach to financing when it was launched last March. Ever since, the party has disclosed new contributions on its website within 10 days of receipt. That is, the party is now doing what B.C.’s Election Act forces it to do annually, just faster. The problem is, no one wanted speedier transparency. Eighty-six per cent of British Columbians do, however, want corporate and union donations banned.

Next month, the opposition NDP will attempt to introduce a bill that would do just that; it would also limit donations and call for Elections BC to review fundraising regulations, or the lack thereof. The Greens, disgusted with the system—and adept at finding new ways to hive off support from the NDP—began voluntarily refusing donations from corporations and unions earlier this year. Though the opposition is united on the question, the Liberals are expected to defeat the bill a sixth time.

Nevertheless, on Jan. 23, Clark dined with Kelowna’s elite at a $5,000-a-plate event at the Mission Hill Winery, which has pumped $200,000 into B.C. Liberal coffers since 2005. (The next day, the premier refused to name her guests, who were shuttled into the winery in dark vehicles, cloaked in secrecy.)

Clark, perhaps the best retail politician to ever emerge from B.C., is widely expected to cruise to a second majority in B.C. in the coming May election, giving the Liberals a record fifth term. Still, she’d do well to consider the main take-away from Donald Trump’s stunning, unforeseen win last November. Pitchforks come out when people get angry over the influence wielded by political donors, when a cozy system appears to benefit only the ruling class, when regular folk feel ignored and defeated, and politicians don’t notice.

Correction: A previous version of this post suggested that B.C.’s conflict of interest commissioner Paul Fraser’s son sits in her Cabinet. He sits on her executive council, as a deputy minister.