Is Tom Mulcair the best opposition leader since Diefenbaker?

Brian Mulroney says Mulcair is a great Opposition leader. Is that reasonable? And what does it matter?

Prime Minister Stephen Harper answers a question during Question Period in the House of Commons on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Tuesday May 28, 2013 as NDP Leader Tom Mulcair looks on.THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld

Share

Making the rounds this week on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of his first majority government, Brian Mulroney repeatedly offered a historic assessment of Thomas Mulcair‘s performance as leader of the official Opposition: Mr. Mulcair is, in Mr. Mulroney’s estimation, “the best Opposition leader since John Diefenbaker.”

This, of course, sent me to the archives to review the last half-century of Opposition leaders.

If Mulcair is to be considered the best Opposition leader since Diefenbaker, that would put him ahead of each of the following on that score (excluding interim and acting leaders): Robert Stanfield, Joe Clark, Pierre Trudeau, Brian Mulroney, John Turner, Jean Chretien, Lucien Bouchard, Michel Gauthier, Gilles Duceppe, Preston Manning, Stockwell Day, Stephen Harper, Stephane Dion, Michael Ignatieff and Jack Layton.

Trudeau, Layton and Duceppe each held the post for less than a year, Mulroney and Gauthier for barely that long (384 days and 391 days, respectively). And it might be easily agreed that Mulcair has fared better than Ignatieff, Dion and Day. That leaves a group of eight to debate: Stanfield, Clark, Turner, Chretien, Bouchard, Manning, Harper and Mulcair.

It would be an interesting, but also somewhat novel, debate. The leader of the official Opposition is, indisputably, an important post: more important than most cabinet ministers and vital to our system of government. The Opposition leader might be our most prominent parliamentarian and the embodiment of the legislature’s role as a forum of accountability. It is, or should be, a massive responsibility.

But it’s also been deemed both the hardest and the worst job in British politics. You are, in theory, the leader of the government-in-waiting, but you have none of the advantages of power. Except perhaps in a minority government situation, you can’t really do anything beyond hope to be seen pressuring and sticking it to those who can. You have to differentiate yourself as much as possible without seeming misguided. You might not want to find yourself on the wrong side of popular decisions, but you don’t want to be seen too often agreeing with the government. In a minority situation, you might be regularly tasked with deciding whether the government survives or falls. It is both a job and an audition. And if there’s a competent third-party leader, you have to fend off him or her, too. (Ignatieff was ultimately surpassed by Layton, and Mulcair is now struggling to compete for attention with Justin Trudeau.) And whether you end up getting promoted might depend mostly on whether the guy across from you in the prime minister’s chair ends up exhausting the public’s patience before your party loses patience with you.

You shouldn’t feel any sympathy for the leader of the Opposition, but it’s not an obviously easy job to do right.

It’s also not really a job you can imagine any normal person ever really aspiring to, at least, not as one’s ultimate goal. Leader of the Opposition is something you do if you have failed or not yet succeeded in becoming prime minister. In that way, describing someone as the greatest Opposition leader might be roughly akin to celebrating the best silver medallist in Olympic history. It’s all very good to win a silver medal and you should be proud of yourself, but, well, you know, it’s not gold now, is it?

So what precisely would qualify one as a great leader of the Opposition? Succeeding in the House as a force for the government to reckon with? Or succeeding in succeeding your opposite as prime minister?

Eleven leaders of the Opposition have ended up becoming prime minister (without having been prime minister first): Alexander Mackenzie, Wilfrid Laurier, Robert Borden, William Lyon Mackenzie King, R.B. Bennett, John Diefenbaker, Lester B. Pearson, Joe Clark, Brian Mulroney, Jean Chretien and Stephen Harper.

Twelve leaders of the Opposition never got to the prime minister’s spot from there: Edward Blake, Charles Tupper, Robert Manion, John Bracken, George Drew, Robert Stanfield, John Turner, Lucien Bouchard, Preston Manning, Stockwell Day, Stephane Dion and Michael Ignatieff. (Arthur Meighen’s case exists somewhere between these two groups.)

The first group is probably more fondly remembered than the second. But how much of that is simply due to the fact that each ended up becoming prime minister? This is where a very close reading of the tenures of the leaders of the Opposition, particularly that second group, is necessary. Somebody should probably write a book. (I’d definitely read a book about the men who didn’t become prime minister.)

Mulroney could probably build a decent case for Mulcair. In the abstract, the NDP leader has been some of what I imagine you’d want in a leader of the Opposition: tough, demanding, forceful, confident. He also just sort of looks like the sort of person you’d want berating and mocking the government on a daily basis—broad and solidly built, a bit uptight, bearded (we really missed out in never having Bill Blaikie as opposition leader, or Speaker). His handling of the Duffy-Wright scandal will be a reference point for the foreseeable future in any discussions about how question period should operate, or how the leader of the Opposition should approach a controversy (I don’t think it was perfect, but it was very good). His performance before a parliamentary committee in May was also at least entertaining. I can’t comment on how Manning or Chretien or Turner or Clark handled the job, but I suppose I can imagine Mulcair comparing well.

And yet, if he goes down as one of our better leaders of the Opposition, but never becomes prime minister, how satisfied will Thomas Mulcair be with his time as NDP leader?

This entire train of thought did lead me to wonder about the historical service time of Opposition leaders. On that score, Mulcair has already surpassed several of his predecessors and will crack the top 15, if he remains leader of the Opposition through until an election next fall.

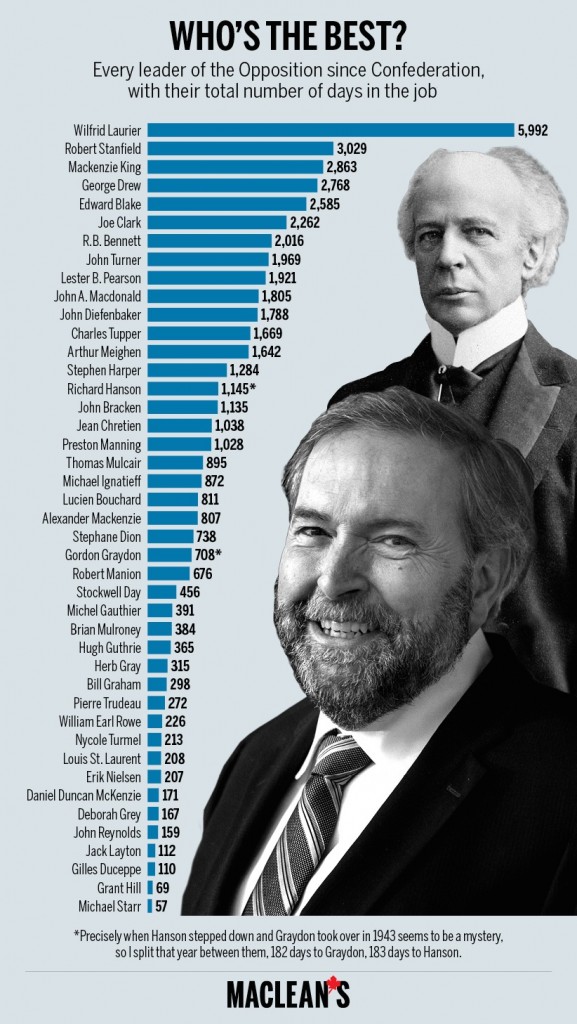

With the assistance of spreadsheet guru Nick Taylor-Vaisey, here’s every leader of the Opposition since Confederation, with their total number of days in the job:

Two takeaways from that list.

First, holy cow; Wilfrid Laurier spent a long time as leader of the Opposition. That’s 16 years as Opposition leader—in addition to the 15 years he was prime minister. (He was an MP for 44 years, 10 months and 17 days, our longest-serving parliamentarian by a full four years. John A. did some important things and was probably more fun at parties, but should Laurier be our Parliament’s greatest icon?)

Second, poor Bob Stanfield. He should probably be considered the patron saint of Opposition leaders.

*Precisely when Hanson stepped down and Graydon took over in 1943 seems to be a mystery, so I split that year between them, 182 days to Graydon, 183 days to Hanson.