A word of advice for newly un-muzzled federal scientists

If government science becomes a political football, ministers’ demand for science advice, and the need for government scientists, will decline.

Share

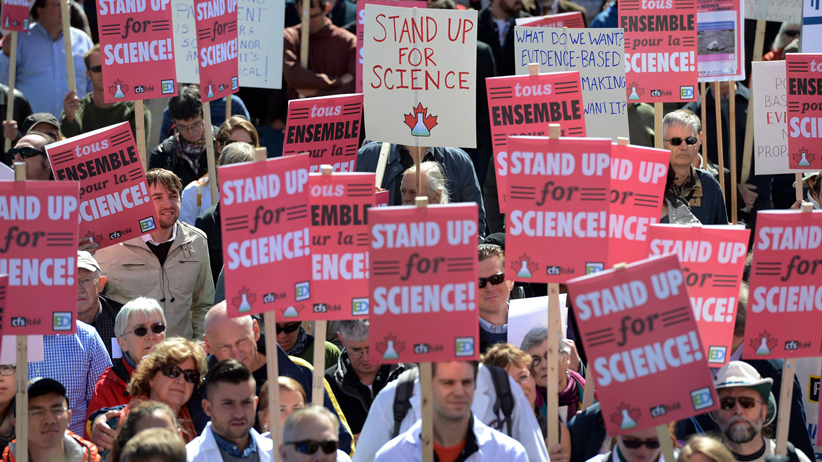

One of the many commitments of the new federal government is that federal government scientists will be “un-muzzled,” i.e., free to talk to the media about their research. The commitment comes as a predictable response to the heavy-handed communications practices of their predecessors. In itself, “un-muzzling” federal scientists makes a great headline—easy to communicate and understand. But underneath it lies a complicated issue: the tension between government scientists’ natural desire to discuss their research and their ethical duty as public servants to support whatever government voters elect. Within this tension lies a danger for government scientists that may not be fully appreciated.

To understand the tension, it’s useful to remember one of the stated “values and ethics” of federal public servants: the duty to “loyally carry out the lawful decisions of their leaders, and support ministers in their accountability to Parliament and Canadians.” A short-hand version of this ethical value is: “fearless advice and loyal implementation.” In other words, non-partisan, professional public servants must give their best advice to ministers, then loyally support the lawful decisions of the democratically elected government, regardless of their personal views. If they find it impossible to support the government, they can resign and make the reasons for their resignation public. Such resignations are rare, but they happen often enough to remind us of both the ethical duty and the integrity of public servants.

The advice that ministers consider in making decisions comes in many forms. Scientific, economic, social, legal and political considerations all may be relevant. Voters entrust ministers, not unelected public servants, with the responsibility of weighing the various factors and coming to a decision. Ministers need to be ready to defend their decisions and actions before Parliament and the public. Thus, when ministers make decisions, scientific evidence is but one of the things they may need to consider.

Herein lies the danger for government scientists. As public servants, government scientists need to provide ministers with the best scientific evidence regarding the policy issues and, at the same time, loyally implement whatever lawful decisions ministers take. Anything government scientists say that can be interpreted as criticism of a government decision is contrary to their ethical duty as public servants. If scientists write or say things publicly that can be interpreted as critical of a lawful government’s decisions, they should be prepared to resign their positions in the public service.

A common and natural issue that arises whenever journalists talk to government scientists is whether a minister’s decisions are consistent with scientific evidence. The other considerations that come into play are often ignored. Thus, it is a common occurrence in media interviews for government scientists to find themselves facing a difficult question: Are the government’s decisions consistent with your scientific work?

Can this tension be managed? Yes, but only with care and restraint. Clearly, government scientists should continue to make their work publicly available by publishing it in scholarly journals and discussing it in scientific conferences. When speaking with journalists, they should be cautious and avoid talking about policy issues that are the prerogative of the minister. For their part, journalists should respect the ethical duty of government scientists to support the government and avoid putting them in apparent conflict.

Finding the right balance in the new world of un-muzzled scientists in government will not be easy. Ultimately, if government science becomes a political football, ministers’ demand for science advice, and the need for government scientists, will decline. Wouldn’t it be ironic if the desire to “un-muzzle” government scientists ended up leading to less scientific evidence in government decision-making?

Paul Boothe is Professor and Director of the Lawrence Centre for Policy and Management at Western’s Ivey Business School. He is a former federal and provincial deputy minister.