Canada doesn’t have its own Bernie Sanders. That’s a problem.

Historian Ian McKay explains why in Canada, a good socialist is hard to find

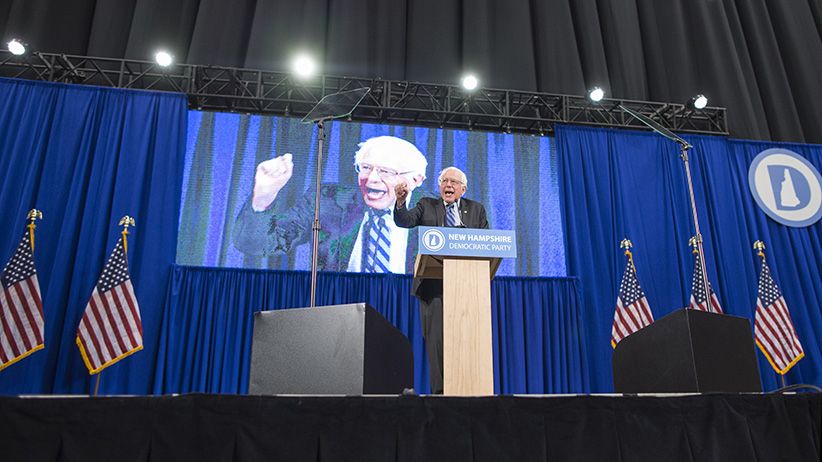

MANCHESTER, NH – SEPTEMBER 19: Democratic Presidential candidate Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) talks on stage during the New Hampshire Democratic Party State Convention on September 19, 2015 in Manchester, New Hampshire. (Scott Eisen/Getty Images)

Share

Sen. Bernie Sanders is more than just an American’s idea of a leftist—which is to say, a liberal. He unabashedly refers to himself as a socialist, advocating for things like free college tuition and the breakup of major banks. Once electoral poison in the U.S., Sanders’s unapologetic reformism has propelled him into contention with Hillary Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination. In the U.K., meanwhile, newly elected Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has turned his party on its ear, jettisoning the so-called Third Way policy compromises that made Tony Blair electable by mainstream voters in the late 1990s. There, as in Washington, socialism has regained a measure of political currency.

Related: A weekend with Bernie (Sanders)

So what about Canada, where New Democrats at times sound indistinguishable from Liberals? Is there room in this country for a figure with a purer socialist bent? To find out, I contacted the man who wrote the book on the Canadian left, Queen’s University historian Ian McKay. His 2005 book Rebels, Reds, Radicals: Rethinking Canada’s Left History was a prelude to a soon-to-be-published two-volume history on the subject. McKay was recently named Wilson Chair of Canadian History at McMaster University in Hamilton.

Q: Until Corbyn, I wondered if we’d ever see an avowed socialist leading a party in a Western democracy again. Why do you think he and Sanders are gaining traction?

A: You’ve got a pattern of income equality that’s almost unheard of. Some people would say it recalls that of the early 19th century, or even before the Industrial Revolution, and I think it’s just bound to create some kind of pushback. In the case of Corbyn, you’ve got a strong socialist tradition in Britain. It’s not easily stereotyped as just a crazy, minority, out-there kind of position, and it’s just starting to resurface.

Q: In Canada, of course, the mainstream left is defined by the NDP. Is it possible for someone with a more radical agenda to gain a meaningful following here, inside or outside that party?

A: If that person comes off sounding like a pure ideologue, I would say no. If he or she comes off sounding like Tommy Douglas, who spoke in down-to-earth language that everyone could understand—but was, in his or her core, very radical—then I think it can happen.

Q: We’ve had them in the past.

A: Yes, and I think that’s what you’re going to see in the next 10 years: movements that address income inequality in understandable, common-sensical language. You don’t need to be a far-out radical to grasp why it’s wrong for a CEO to make as much in an hour as an average worker makes in a year. You don’t need a Ph.D. to see unfairness in someone who basically moves numbers and deals in abstractions all day in an office earning so much more than someone who physically works and does what society needs.

Q: What kind of politician does it take to make that message resonate?

A: I think Corbyn and Sanders are the first drafts of that kind of politician. The great thing about being that type of leader is that you don’t need everyone agreeing on everything—on religion, on questions of identity, on the Constitution. You just need agreement that there is something amiss in a society that has this level of inequality, that this is the issue of our time. The current campaign has been such an exercise in diversion, where issues that are really important and central to people are almost never discussed.

Q: Odd, because a lot of the public conversation over the past couple of years has centred on economic inequality and the ideas of people such as Thomas Piketty [the French economist who charted wealth concentration in developed countries]. Is that testimony to the nature of political campaigns today—that we wind up dwelling on symbolic issues such as niqabs at citizenship ceremonies?

A: Yes, and to an electorate, nearly half of which is not going to vote. Once you engage that 50 per cent with the sense something can actually be done, and once you have a politician who can present a meaningful program, watch out. Then you’ll have Saskatchewan in 1944 [when voters brought in Douglas’s Co-operative Commonwealth Federation]. Douglas’s genius was to speak in ways you could identify with, whether you were, say, Catholic or Protestant. And remember, there were deep rifts in the province at the time. Saskatchewan had a Ku Klux Klan in serious business in the 1920s, acting almost as a behind-the-scenes government. Douglas united people by speaking strongly about a politics of equality in a way that didn’t put them off, and brought off a bit of a miracle.

Q: How close are the parallels between those times and today’s political conditions?

A: I think, in many ways, we’re in a more extreme situation. It’s harder for people to think outside the box. The Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci talked about hegemony, or the capacity of those who rule us to influence our language and the things we consider might be possible. It’s the force that determines what is just a crazy idea versus what sounds sensible. I think Canadians are caught up in a classical liberal hegemony that says there are levels of state involvement in the economy that are crazy; that you have to accept what you get in market outcomes and that you don’t question it.

Q: That leads us, I suppose, to Tony Blair and the Third Way model, which accepted the market economy while asserting concern for the underprivileged. How deeply did its success influence the Canadian left?

A: The force of liberal assumptions in Canada is enormous: the acceptance of free enterprise, conventional property relations, as well as ideas of equality that come down to the individual. I see it in this election, where you essentially have a large number of liberal parties jockeying for position. But those assumptions don’t answer the problems of income inequality, nor do they answer the environmental crisis. So I do expect there will be a rethinking of what is legitimate politics. But it requires a leader who speaks in language that doesn’t set off alarm bells. That may be the genuis of Sanders and, to a lesser extent, Corbyn: They don’t set off other alarm bells, as if they want to create some restrictive, regimented society. That’s not their agenda.

Q: Where might we find that type of leader in Canada today?

A: They’re all over the place. They just don’t get into the centre of political conversation. If you think of [the Indigenous people’s rights movement] Idle No More, of the Occupy movement, of Naomi Klein and all of the people she activates—this is not a small constituency. What they need is to find a powerful voice in the federal arena.

Q: People in the NDP complain about the long shadow cast by Bob Rae, an NDP government in Ontario that was seen as fiscally irresponsible in the early 1990s. Is that what’s really been keeping them out of power?

A: The Bob Rae situation has played powerfully against the NDP, to the point that he became a two-word rebuttal for any socialist argument. That drastically oversimplifies Ontario’s circumstances at that time; I would defy any government to come into power with an uncomplicated reponse to that situation. But the NDP has been affected ever since. Look at the Nova Scotia NDP. They were just transfixed by the idea of balanced budgets. It became an absolute mantra, to the point most economists would find almost fetishistic. I think it’s why they lost power.

Q: Do you hear echoes of that fetishism in NDP Leader Tom Mulcair’s promise to balance the federal budget?

A: I can see why he does it. I’m not sure it was the wise thing to do. But you’re right. What you’ve got here is the long shadow of Bob Rae, a left-liberal who had no real idea of the society he was trying to change, or even whether he wanted to change it. He just wanted to preserve it.

Q: The centre of gravity for the left in Canada—and for the NDP—increasingly lies in Quebec. What complication does that pose for the NDP?

A: Well, let’s give credit to the NDP. When faced with human rights issues like Bill C-51, on which the the Liberals basically folded, and on the niqab in Quebec, they’ve taken the unpopular, difficult stance and defended it. On these issues, you’re seeing what consistently principled politics leads to. It might not play well in the polls.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]