For the record: The leaders, the economy, the talking points

With much talk about the economy to come, a review of the video tape from the last time the leaders met to discuss it

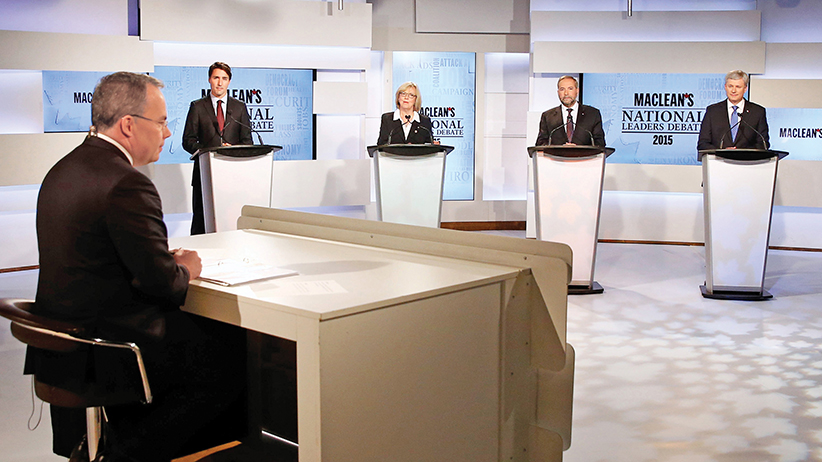

The last rehearsal before the Maclean’s Leaders Debate. (Photo credit: Dillan Cools/Maclean’s)

Share

When Maclean’s hosted a national leaders debate earlier this summer, moderator Paul Wells kicked things off with questions on the economy. Staffers had prepped their leaders, and everyone on stage came armed with pre-packaged answers, rebuttals and zingers on jobs, taxes, deficits, and spending plans. You name it. The leaders’ derived their answers from Bank of Canada reports, Parliamentary Budget Office forecasts, Statistics Canada tallies, and private economists’ assessments. As they prepare for The Globe and Mail‘s debate on the economy, the leaders are consulting the latest numbers. So what’s changed? In short: a lot.

Some of the leaders’ loudest messages on the economy during the Maclean’s National Leaders Debate won’t fly when they meet on the Calgary Stampede Grounds. As they rev up their rhetorical engines once again, we recall what they said on three key economic files—taxes, deficits and pipelines—when they last gathered in City studios on Aug. 6.

TAXES

Harper preaches a low-tax plan

The simplest pitch on taxes belongs to Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who constantly reminds voters of his party’s plan to cut taxes. One of the knocks against Harper’s approach is that lower taxes hamstring government spending. But the PM countered the claim that corporate tax cuts mean big business pays less. “The reality is not only did these tax cuts help create jobs, but our tax revenues actually went up from the business sector,” he said. What are the facts? The Tories have shaved six percentage points off the corporate tax rate since the 2007 federal budget, and total revenue—rocked by the 2008-09 recession—has ticked up in nominal terms every year since 2010. But the claim that revenues are higher than before the tax cuts is only true if you ignore inflation. In real terms, the government took in slightly less corporate tax revenue in 2015 ($39.2 billion) than it did in 2007 ($41.2 billion in 2015 dollars), before the cuts began.

Trudeau won’t touch big corporate taxes

If Harper and Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau agree about anything, it’s that big corporate tax rates are fine where they are. Trudeau channeled Harper as he tore a strip off NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair’s plan to hike corporate tax rates. “We need more investment. We need to create more jobs,” he said. “So his plan to hike corporate taxes is simply pandering to the people who like to hate corporations, but we need that growth.” Trudeau admitted that the money for his promises will have to come from somewhere, and he points the finger at Canada’s wealthiest taxpayers. Under a Trudeau government, anyone who earns more than $200,000 would enter a new bracket that pays more at tax time.

Mulcair won’t touch personal income taxes

Mulcair defended his plan to stand pat on personal income tax. “We think that Canadians are paying their fair share,” he said. “Canada’s largest corporations are not paying their fair share.” Mulcair pointed to New Brunswick, a province where he says residents face a 58.75 per cent personal income tax rate. (Indeed, the Canada Revenue Agency says anyone in New Brunswick who earns more than $129,975 stares down a 58.86 per cent tax rate). Mulcair said a tax hike on the wealthy would discourage doctors from moving to a province that doesn’t have a university with a faculty of medicine. If the Liberals agree with the Tories on corporate tax, it’s here where the NDP agrees with the Conservatives.

DEFICITS

Harper boasts a balanced budget

The leaders offered starkly different assessments of Canada’s bottom line. Harper claimed his government had tabled a balanced budget this year, but that was merely prelude. “We have not only a balanced budget, we have the lowest debt levels in the G7 by a country mile, by far,” he said. “We have by far the best fiscal situation going forward. All analysts can see that.” Harper didn’t know it at the time, but the Department of Finance has since reported that the feds recorded a budget surplus in 2014-15, a full year ahead of the government’s schedule (though in line with earlier estimates, and maybe not all that surprising). Harper’s position is also buoyed by a $5-billion surplus his government has recorded over the first three months of 2015. The Finance department itself takes those numbers with a grain of salt, but it’s certainly better news for the PM than a deficit.

Mulcair derides Harper’s deficits

In August, Mulcair was having none of Harper’s balanced-budget claims. The NDP leader said the PM “is trying to hide the fact that we are in a deficit again.” He also accused Harper of running “eight deficits in a row.” To get there, the NDP counted the six reported deficits from 2008-09 to 2013-14; added a likely deficit from 2014-15; and predicted another deficit in 2015-16, counter to Harper’s claims, based on Parliamentary Budget Office calculations. Mulcair’s problem: that pesky $1.9-billion surplus in 2014-15, which is wind in Harper’s sails. Whether or not a faltering economy “unbalances” the 2015-16 budget, Harper’s opponents can no longer say eight, or even seven, deficits in a row.

Trudeau also derides Harper’s deficits

Trudeau repeated Mulcair’s eight-deficit refrain, and he added a Liberal cherry on top. “He took a decade of surpluses and turned it into eight consecutive deficits,” Trudeau said of Harper, reminding everyone at home that Liberals balanced the budget every year between 1998 and 2006. He’s since campaigned with the architects of those surplus years: former prime ministers Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin, as well as former finance minister Ralph Goodale. (A few weeks after the debate, Trudeau pitched his own deficit spending for up to three years—a popular idea among economists, but a tougher sell after he repeatedly slammed Harper’s record.) More claims from Trudeau during the debate: “We’re the only country in the G7 that’s in recession right now. [Harper] has no plan to get out of it. And we just found that wages are falling as well,” he said. The recession claim is largely true: Statistics Canada has reported two straight quarters of GDP contraction, which meets the Conservatives’ own definition of a technical recession. The wages claim is partly true. A few days before the debate, StatsCan reported reported that non-farm wages fell between April and May. The hitch: Average wages had actually increased 1.4 per cent over the past year.

PIPELINES

Harper defends his pipeline plan

Harper is categorical on Canada’s pipeline debate. He supports more pipelines than any other party, and he’s convinced his opposition won’t support any. “All of these parties have opposed all of these projects before we’ve even had environmental assessments. That’s not the responsible way you do things.” Harper was fudging the truth. Elizabeth May’s Green Party is the only party that opposes all new pipelines. Trudeau supports the contentious Keystone XL pipeline that would carry crude to American refineries to the south. Neither he nor Mulcair has completely ruled out the Energy East pipeline, though both have set high bars for approval. Only on the Northern Gateway pipeline, which would run from Alberta’s oil patch to the B.C. coast, does Harper face a united opposition. He likely won’t recognize that fact as the three leaders debate in Calgary.

Mulcair opposes Keystone XL

There’s no advantage Mulcair can gain from Trudeau’s opposition to Northern Gateway or Liberal waffling on Energy East, so the NDP leader zeroes in on Keystone XL. He paints his chief rivals as outsourcers, claims Keystone XL “represents the export of 40,000 jobs,” and vows to create those jobs in Canada. Mulcair says Energy East, which he won’t explicitly support until a better assessment process is in place, “could be a win-win-win: better price for the producers, more royalties for the producing province. It could also help create those jobs in Canada.”

Trudeau attacks Mulcair’s pipeline pitch

Whatever Mulcair actually thinks of Energy East, his comments have varied in English-language and French-language media. He tends to emphasize the pipeline’s potential when he’s talking to an English crowd, and ratchet up his skepticism in front of a French audience. Trudeau pounced on that habit. “That kind of inconstancy, quite frankly, isn’t the kind of leadership we need for Canada,” he said. The funny thing is that Liberals and New Democrats appear to agree on the conditions for pipeline approval. They would both strengthen environmental laws, work more closely with Indigenous groups, and earn a so-called “social licence” to build pipelines.