Here’s why Bill Morneau didn’t sell his stock or set up a blind trust

The embattled finance minister was told he didn’t technically have to, but the reason isn’t going to help him fend off critics

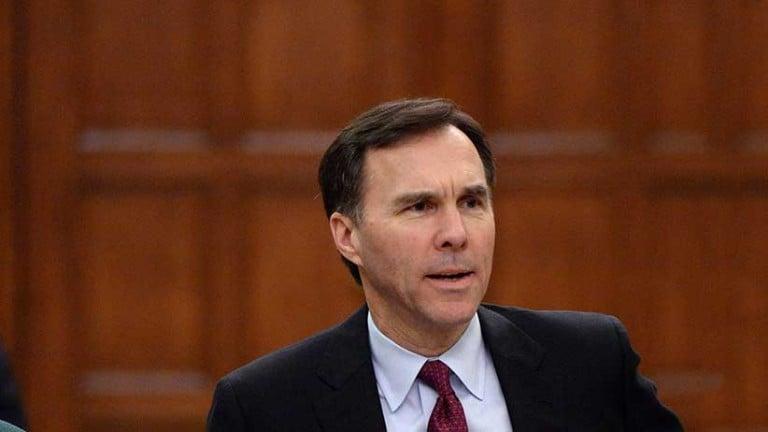

Finance Minister Bill Morneau appears at Commons committee for pre-budget consultations on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Tuesday, Feb. 23, 2016. (Sean Kilpatrick/CP)

Share

Bill Morneau wasn’t in the House today to face a sustained, gleeful onslaught from Conservative and NDP MPs over why, after he became finance minister, he didn’t either sell his shares in Morneau Shepell—the pension management company he built up from a family business to a major publicly traded corporation—or put his stake in a blind trust.

Those are the two options clearly spelled out in the federal Conflict of Interest Act. Morneau will remain under intense pressure to explain more precisely and publicly why, when he made the leap from business to politics, he opted for a third way of avoiding conflicts. Today he sent a letter, which he released to the media, to federal Ethics Commissioner Mary Dawson, declaring that he has followed her advice on all this “diligently,” but is open to revisiting the matter now, since “these recommendations have recently been the subject of increased public scrutiny.”

READ: Throw another minister on the bonfire: the ballad of Bill Morneau

On exactly what Dawson advised him to do with his multimillion-dollar holdings, a spokesman for Morneau told Maclean’s she sent him a private letter, dated Feb. 2, 2016, in which she stated that he did not have to set up a blind trust. Here’s the key line from Dawson’s letter to Morneau that his office provided: “Considering that you do not hold controlled assets as contemplated under section 17 of the [Conflict of Interest Act], a blind trust agreement is therefore not required under section 27 of the Act.”

Dawson’s reasons for deciding that Morneau’s shares in the company he formerly headed didn’t qualify as “controlled assets” now stands as a central mystery in this controversy. Guidelines from Dawson’s office state that controlled assets include “publicly traded securities of corporations” whose value might be “directly or indirectly affected by government decisions and policy.” That language certainly seems to cover any shares Morneau still owns in Morneau Shepell.

WATCH: Opposition parties turn up heat on Morneau

However, in an email to Maclean’s, Dawson’s office pointed to a broad exception, without commenting directly on Morneau’s specific holdings. Her communications staff confirmed that public office holders, like Morneau, must divest or place in a blind trust any controlled assets they “hold directly.” The email went on, though, to add: “This divestment requirement does not apply to any controlled assets that reporting public office holders hold indirectly, through a holding company or other similar mechanism.”

It seems likely this is why Dawson decided Morneau didn’t have to sell his shares or put them in a blind trust. But having to explain that his shares are in a “holding company or similar mechanism” is unlikely to make for compelling political rhetoric. Even Dawson doesn’t approve of the distinction existing under law. Her staff pointed out that, back when the federal Conflict of Interest Act was last reviewed in 2014, Dawson recommended that it be amended to require divestment of “controlled assets held indirectly as well as directly.”

That change wasn’t made. Morneau would probably be better off today if it had been.

UPDATE: Oct. 18: Surprisingly, Dawson’s office told Maclean’s late Wednesday afternoon that it has no written guidelines for the sort of situation facing Morneau, where the issue is the difference between directly owning so-called “controlled assets,” like shares in a public corporation, and owning them through some sort of holding company. “We do not have a guideline document relating to the…. prohibition against reporting public office holders holding controlled assets,” an official in Dawson’s office said in an email. Although the Conflict of Interest Act only refers to holding controlled assets, the ethics commission points to other federal laws that draw a distinction between assets held directly and those held indirectly.

MORE ABOUT BILL MORNEAU:

- Trudeau’s pandering small business tax cut will do nothing for the economy

- The Prime Minister’s tax reform damage control tour

- Liberals to announce small business tax cut

- What tax grab politicians in Canada could learn from Hong Kong

- Justin Trudeau’s money pit, and those working hard to join it

- Trudeaumania Two is starting to fade

- Throw another minister on the bonfire: the ballad of Bill Morneau

- Bring back the $10,000 TFSA