How Canada’s incoherence on climate is killing Keystone

In the absence of ambitious climate policies, Edmonton and Ottawa have decided on an ambitious program of wordsmithing

Share

There’s no shortage of blame being passed around in the wake of another delay in the U.S. regulatory approval process with respect to TransCanada’s Keystone XL pipeline which, it was announced last Friday, will now drag on for at least another six months. Among other reasons cited for the decision, the Calgary Herald’s Deborah Yedlin and others have cited a lack of greenhouse gas policies applied to Canada’s oil sands. Yedlin is direct, saying that, “the evidence to date suggests (that the Harper government hasn’t listened to what is being said in Washington) because the Harper government has not moved on anything resembling a policy on greenhouse gas emissions.” I think she’s right, to a point, but I think the problem is not that we haven’t been listening, but that our governments, both in Edmonton and in Ottawa, have yet to establish a coherent vision on anything which includes the words climate change and oil sands.

From the moment President Obama delivered his climate change speech in June 2013, stating that the Keystone XL pipeline would only be approved if it does not, “significantly exacerbate the problem of climate change,” pipeline proponents have spun 180° from arguing that the Keystone XL pipeline would change everything to trying to argue that, for the most part, it would change nothing. We frequently hear now that the oil sands will still be produced, and will still get to market, no matter what. This, of course, might motivate people to ask why we are building the pipeline in the first place, and the Prime Minister’s Office is there for you with an answer: “this project will create tens of thousands of jobs on both sides of the border…” So, the pipeline is now a make-work project in an industry in which we hear about labour shortages every day? Proponents of the pipeline can no longer talk about the pipeline on its actual merits because that would involve talking about improving the economics of oil sands production which we can’t talk about because someone might link that to an increase in emissions. Keystone XL went from the magical pipeline which will change everything to the non-essential pipeline which changes nothing, because we don’t know how to respond to one presidential speech.

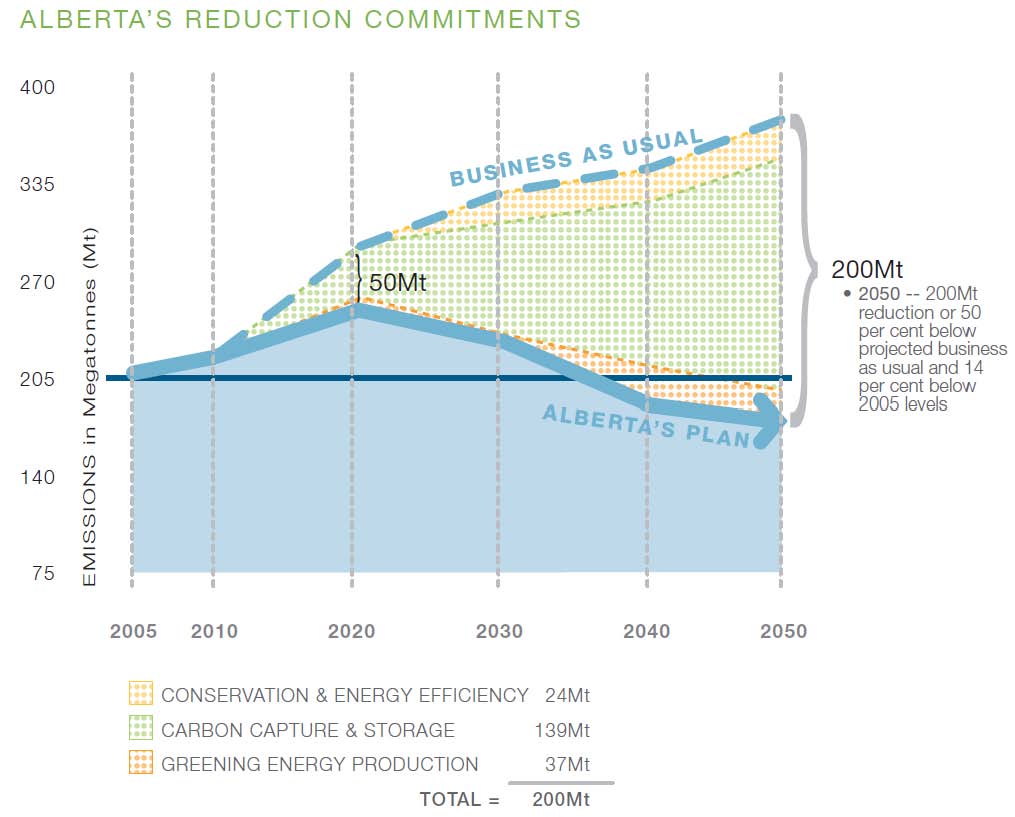

It’s unlikely that an updated climate change policy in Alberta or any new initiative at the federal level alone will solve the problem because our ambition for setting policies does not match our ambition for making promises or setting targets. For example, when Alberta released its Climate Change Strategy in 2008, it committed to a set of targets which were based, although not publicly, on a policy—there was even a wedge diagram of what that policy would achieve. That policy included, “an escalating economy-wide carbon charge increasing from $15/tonne in 2008, to $30/tonne in 2020, $60/tonne in 2030, and $100/tonne in 2050 and a strict regulation that all large, new industrial facilities are required to incorporate carbon capture and storage by 2015 wherever possible.” Don’t believe me? See the Report of the Alberta Auditor General (PDF, p. 99) on the subject.

Unfortunately, what Alberta had the political will to implement was a $15/tonne charge on large industrial facilities which applies only if they exceed their allowable emissions intensities. The ambition of their targets was an order of magnitude above the ambition of their policies. The same is true at the federal government level. Modelling work consistently concludes that, in order to reach the targets to which the current government committed at Copenhagen (a 17 per cent reduction in emissions relative to 2005 levels by 2020), policies equivalent to an economy-wide carbon tax of $100/tonne or more would be required—ambitious targets, indeed. Again, the government in Ottawa has shown nowhere near the same ambition when it comes to setting policies. Some meaningful policies including an effective ban on new coal plants and stringent regulations on new cars and trucks have been implemented, but the government’s own modelling clearly shows that we will fall far short of our commitments unless aggressive new policies are implemented across the economy in short order.

As an antidote to our lack of ambition on policies, our governments both in Edmonton and in Ottawa have decided to work on an ambitious program of wordsmithing. We talk about emissions reductions, when what we really mean are reductions in the rate of growth of emissions. Our government representatives tell us that they are still committed to their targets, when their own modelling tells them that their policies won’t even get them close. When our government talks about growing oil demand, they cite scenarios for fossil fuel consumption consistent with global emissions growing far beyond the levels to which they committed jointly with other countries in international climate change negotiations. A new policy for oil sands emissions at the Alberta or Federal level is not going to solve any of these problems, because the ambition simply isn’t there.

How could Canada solve this problem? As I wrote when the Harper government elected to withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol, if we were really listening to what the decision-makers were saying in Washington, we’d be looking at how we could offer a climate change approach with three elements. First, we’d need a clear national goal. Second, we’d need a set of policies which, when applied in Canada, would have a reasonable chance of achieving that goal. Third, and most importantly, we’d need to show how these policies, if applied elsewhere in the world in addition to here, would translate to meaningful mitigation of climate change. These are the same criteria once laid out by our Prime Minister who said that, “Canada does have a duty to act,…(that)…we cannot repeat our previous error (of committing to targets we are not prepared to meet and)…we must set targets that are achievable.” We should complete what the Prime Minister said we should do at that point: start, “by asking ourselves some hard-headed questions, like what are realistic emissions reductions targets for Canada and how exactly will we achieve them.”

If Canada can demonstrate that there is a role for oil sands expansion under national and global energy policies consistent with the 2°C climate change mitigation goal to which our government has signed-on, it would be much more difficult for opponents to block infrastructure such as Keystone XL for which a strong economic case exists. If our governments are unprepared, unwilling, or unable to do so, they’ll make rejection of this and future pipelines much easier. As Ms. Yedlin suggests, perhaps it is time to listen to the decision-makers.