How the PM’s residence became a nightmare at 24 Sussex

Imagine living with asbestos, knob-and-tube wiring, a leaky roof. Anne Kingston explains why prime ministers make terrible tenants.

24 Sussex Drive as it appeared before 1950, before it was renovated and transformed into the prime minister’s residence. The 1950-51 renovation removed much of the decoration seen in this photo, including the tower and turret. (The Ottawa Citizen)

Credit: Citizen files

Share

Given the tortuous history of 24 Sussex Dr., there’s delicious irony in the fact that Margaret Trudeau—whose disdain for the country’s most famous address is legend—was the one to announce that her eldest son was not moving his family into the Prime Minister’s official residence. A “large, cold, grey mansion,” is how the former wife of prime minister Pierre Trudeau described the place in her 1979 memoir, Beyond Reason, which chronicled the claustrophobia of life in the heavily guarded 34-room house. She was more caustic this summer, calling it the “crown jewel of the federal penitentiary system” on The Residences: Inside 24 Sussex—Home of Canada’s Prime Minister, an upbeat documentary hosted by Catherine Clark, daughter of former prime minister Joe Clark.

It’s a good line, if overly generous. For if Canadian prison inmates were expected to live in a firetrap with no fire-suppression system, next to asbestos, radon gas and mould, human rights groups would protest, and rightly so. Yet for years, it’s been no secret that the home of 10 prime ministers was not merely deficient but dangerous, a property standard insurance companies would not typically cover. Maureen McTeer, Joe Clark’s wife, spoke of electrical circuits overloading. Paul Martin’s wife, Sheila, reported severe drafts in winter. That complaint, and word of similar problems in the Chrétien years, inspired political satirist Rick Mercer to film a segment in 2005, in which he goes to Canadian Tire with prime minister Paul Martin to buy plastic window insulation.

The house’s decrepitude became public in 2008, when then-auditor general Sheila Fraser announced that renovations to the heritage-designated building, a federal government-owned property managed by the National Capital Commission (NCC), were urgently required to repair cracked windows, 50-year-old knob-and-tube wiring, deficient plumbing, a leaky roof, old window air conditioners, a lack of universal disabled access, and “not functional” laundries. The work, estimated to cost $10 million, required the “residents,” as the NCC calls them, to move out for at least 18 months, something then-prime minister Stephen Harper refused to do. The state of the house now is unknown. Photographs of the Harpers’ moving boxes labelled with mould warnings do not bode well.

Now Justin Trudeau’s family is ensconced in the 22-room Rideau Cottage behind Rideau Hall, the 175-room home and workplace of the Governor General, a residence people in the know say is more secure and in much better nick. “What to do with 24 Sussex?” is now being framed in the “Tear down or gut?” lingo of an HGTV reality show. Everyone has an opinion, with former residents and preservationists at odds. Raze the place, McTeer told the CBC. It’s a heritage property, says Ottawa architect Barry Padolsky: “Why replace something old and wonderful with something new and wonderful, when we’re losing part of our legacy? That’s 1950s thinking. It’s 2015.”

Colouring the debate is the current real-estate frenzy, a moment in which a house is no longer merely shelter, but a reflection of its owner’s aspiration and taste. That makes rotting 24 Sussex a symbol of a nation neglectful of its past. “The address has a mythical hold on the Canadian imagination,” says historian and author Charlotte Gray, who lives nearby. “When you say ‘24 Sussex,’ everyone knows what you mean. But they do not have a mental picture of it, unlike the White House, unlike 10 Downing St.”

Instead, 24 Sussex has become Canada’s The Picture of Dorian Gray—invisibly falling into disrepair while the facade never changes in photo ops, with furnishings in the public rooms that haven’t been recovered or drapes replaced, since chintz balloon shades were fashionable in the ’80s. Mercer’s three televised visits, the last a “sleepover” in 2006 with Stephen Harper, provided rare glimpses. That “the 2-4,” as Mercer calls it, has been allowed to fall into disrepair defies logic, he tells Maclean’s. “There is not a single homeowner in this country who does not understand that if you have a hole in your roof, you have one priority in your life and that is to get that hole patched. There is no scenario where you leave that hole, because water will destroy your entire home.” He’s talking about the PM’s official residence, a house owned by Canadians. But, as in all discussions about real estate, much more.

On a mid-November morning, 24 Sussex Dr. stands solidly grey behind a wrought-iron fence and scrim of pines. Though unoccupied, two police cruisers, a limo and a van are parked in the curved driveway. Rust-coloured mums in stone pots flank the front door, a homey touch. The once-Gothic revival mansion, erected in 1867-68 on four acres by lumber baron Joseph Merrill Currier, is not the grandest residence timber money built in the capital, but its vantage point overlooking the confluence of the Ottawa and Gatineau rivers is unrivalled.

It’s also Canada’s Taj Mahal. Currier, later an MP, built the 2½-storey limestone-clad house as a wedding gift for his third wife, Hannah Wright, naming it “Gorffwysfa”—Welsh for “place of peace”—a bid for tranquility after tragedy. His first wife died disconsolate in 1856, after three of their four children perished of scarlet fever. His second wife’s skirt caught in a machine during a mill tour months after their 1861 wedding; she was crushed in front of him. His third marriage was, by all reports, happier: Their house was a glittering social hub; its housewarming brought 500, including then-prime minister John A. Macdonald and his wife, who lived down the drive at Earnscliffe. The property passed to the Edwards family in 1901; massive renovations added a turret and porte cochère.

Transition to official residence began with bad karma: In 1943, the government moved to evict owner Gordon Edwards, an MP known for housing one of North America’s largest collection of impressionist and post-impressionist paintings. As owner of almost all the land along the Ottawa River, the feds said they wanted to prevent the shoreline from being “commercialized.” Edwards’s final years were spent fighting for his house; the case was settled in 1946 with the government paying him $140,000 and court costs.

What to do with it was “a source of friction between bureaucrats and elected officials,” McTeer writes in her 1982 book, Residences: Homes of Canada’s Leaders, a foreshadowing of events to come. In a 1948 parliamentary exchange, then-prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was asked when the government was “going to repurpose” the property. Mackenzie King was vague: “at the appropriate time and depending on circumstances,” he said. The idea of an official residence had been floated. Unlike leaders of other democracies, Canada’s prime ministers housed themselves. Nor was there interest in preserving that heritage. Earnscliffe, home of Sir John A. Macdonald, was sold to the British government in 1930 and is now the residence of the British High Commissioner. “They’ve done a splendid job of upkeep,” says Gray.

By 1950, then leader of the opposition, George Drew, was living in Stornaway in Rockcliffe Park, which had been purchased by group of Conservatives. (The government bought the property in 1970, making Canada one of the few countries to subsidize housing for the runner-up.)

Renovations to 24 Sussex between 1949 and 1951 neutralized the exterior; they also extracted historical grandeur. Bay windows, wood panelling, marble fireplaces, gingerbread trim were removed. So was a morning room, a coach house, the porte cochère and turret. Left intact: the coffered dining room ceiling, one mantel and two chandeliers. Such “modernizing” was typical in a new country built by immigrants, says Padolsky. “Everything new was good, everything old needed to be trashed.”

From the outset, 24 Sussex was a poisoned chalice—a perk with hidden costs. Its first inhabitant, Louis St. Laurent, moved in reluctantly in 1951. His family was settled in Quebec City and he was comfortable in his bachelor apartment. He agreed after insisting to pay rent (a practice until 1971). Unlike American and British official residences, 24 Sussex has no executive function (the Prime Minister’s Office is in Langevin Block), making the house a federally run Airbnb of sorts. Social functions are thrown (lunches, parties, dinners with the likes of Winston Churchill), but true pomp and moments of historical importance take place at Rideau Hall.

Nor has the official house of the prime minister ever held a nationally shared pride of place, as seen in the U.S. America watched Jacqueline Kennedy’s 1962 televised tour of her painstaking restoration of the White House; Canada saw McTeer showing off a $15,000 reno on the cheap. McTeer, no doubt, understood the residence was a convenient lightning rod for what Gray calls the “Ottawa-bashing and bureaucrat-bashing” that took root in the 1960s. “The physical fabric of government was seen to be self-indulgence, a little too comfortable for people living on the taxpayers’ dime,” she says.

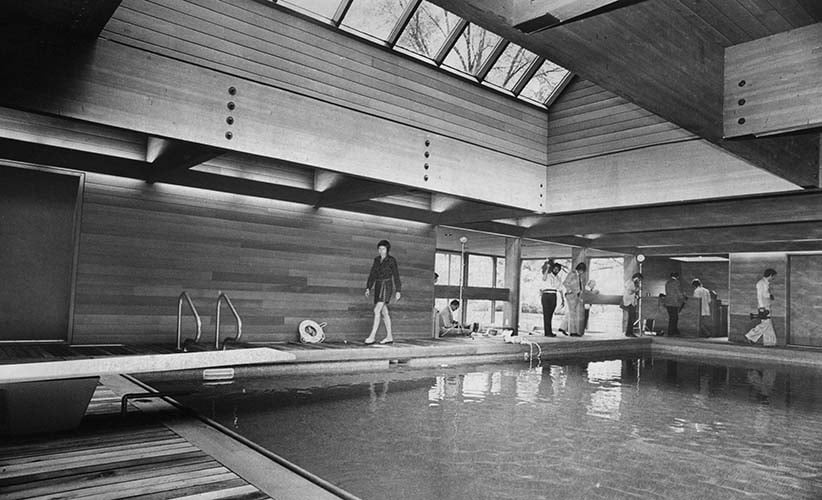

Successive governments upgraded the house (Lester B. Pearson enclosed a winterized patio, Trudeau installed a restaurant-style kitchen and enclosed pool, the Clarks had their modest reno), but spending became an anathema. Trudeau got heat for not disclosing the secret donors who paid for the pool; Mulroney came under fire for “Gucci-gate,” revelations that the Progressive Conservative party spent $308,000 on 24 Sussex and Harrington Lake, the prime minister’s country home. The details—12 m of closets for 100 pairs of shoes, leopard-print carpet, $100-a-role wallpaper —summoned very Canadian “Who do you think you are?” clucking. Liberal MP Don Boudria spoke of “Imelda Marcos-like closets” and “clear abuse of the Elections Act.” It’s difficult to imagine similar outrage over Michelle Obama’s closets.

When the property was designated a heritage site in 1985, the Federal Heritage Buildings Review Office released a revealing summary: The property’s “outstanding feature” is “its location and the view it affords.” The residence, it made clear, is not architecturally special, but good enough: “The house itself is undistinguished, but its size and general appearance are appropriate for the head of Canada’s government,” one of the most Canadian sentences ever written.The report, issued in the Mulroney years, notes that the house “was originally well-constructed and is in a generally good state of repairs.”

It’s been downhill since then, says Gray, with prime ministers wanting to be seen as regular folk. That’s double-edged, she says: “There’s an admirable modesty and dislike of ostentation, but there’s also an almost unbelievably shallow understanding of our history.” Journalist Stevie Cameron, author of On the Take: Crime, Corruption and Greed in the Mulroney Years, who calls 24 Sussex “beautiful,” with “gracious rooms,” agrees: “People have been so burned by stories, they don’t want to look at updating it.” And when you do, you don’t notice decay, says Gray, who visited the house during the Chrétien, Martin and Harper regimes. “It’s all sparkling silver and comfortable chairs. But there are no ‘aha!’ moments,” meaning great art or furniture, “just a stunning view.” It looks fine on TV, Mercer says, “because the wallpaper is nice.”

Mercer wanted to spark outrage after he heard about the state of disrepair a decade ago. “I thought that was ridiculous, a travesty—and that it was short-sighted of Chrétien to refuse repairs,” he says. “You’re basically throwing up your hands and saying Canadians aren’t sophisticated enough to understand that the roof getting fixed is not money going into my personal pocket.” Harper refusing to allow the repairs is “criminal,” says Mercer: “It has nothing to do with the comfort of individuals living in the house; it’s allowing a building like that to fall into disrepair.”

Not spending on 24 Sussex, best known as a cat sanctuary during the Harper years, dovetailed with the Conservatives’ austerity mandate, as well as its promise to return power to the provinces, says architectural historian Leslie Maitland, past president of Heritage Ottawa. “Harper made it clear he didn’t care to spend any money on Ottawa, and he didn’t care to spend any money perceived to be of benefit to him.” Padolsky agrees: “He was doing a Gandhi: willing to live in impoverished circumstances.”

Yet the impoverishment was ultimately the taxpayers’. The PM is just the tenant, a point made by Harper’s hero, Margaret Thatcher, in a forward to No. 10 Downing Street, The Story of a House. She called the British PM’s residence, rebuilt over three decades beginning in the 1960s, a “jewel”: “All prime ministers are intensely aware that, as tenants and stewards of No. 10 Downing Street, they have in their charge one of the most precious jewels in the nation’s heritage.”

When Harper refused to vacate because of the optics, his living conditions aped policy decisions: As his government supported the export of asbestos, he was living with the toxic substance. The house was also an energy sinkhole; the 2012 utility bill for five buildings at 24 Sussex was $69,000: $56,566 in hydro and $12,573 in natural gas, the Ottawa Citizen reported, up 20 per cent from 2006 due to increased energy costs. (Meanwhile, solar panels were installed in the White House in 2013.)

The NCC, which did not respond to Maclean’s request for an interview, has taken on small projects to improve energy efficiency by upgrading windows and insulating the roof. Hundreds of pages released under Access to Information reveal various bills, including: patching and painting for $6,752; replacing “rotting” kitchen pipes for $1,218; fixing and buying appliances for $1,715; and replacing carpets for $1,790.

While doing the least possible at 24 Sussex, the Harper government appealed to the electorate with home-reno tax credits: a permanent home-renovation tax credit to “help generate jobs, jobs for professional tradespeople” was the first big-ticket promise of the 2015 campaign. Meanwhile, both Rideau Cottage and Stornoway have been updated: “The joke is that the leader of the Opposition has a better house,” says one Ottawa insider.

That’s because 24 Sussex exists as an underutilized and neglected national symbol. It’s only one of a long list of federal properties that have been allowed to languish, says Maitland. Gray points to the fact that it took so long for the current restoration of the Parliament buildings, which include repairs to leaking roofs. “It’s unbelievable, especially when you see how well Congress or Westminster are looked after,” she says. “They’re seen as historic sites and shrines to their particular styles of democracy.”

Canada had to change governments for a Prime Minister who lived at 24 Sussex as a child to say he’s not going back. “I don’t blame anyone—left or right—for not wanting their children to sleep in a bedroom with asbestos,” says Mercer. “They say it’s not a problem unless it’s disturbed. Well, leave it to a 10-year-old to disturb it.”

Mercer believes in preserving heritage buildings, but not this one: “If it was up to me, I’d save a fireplace, put up a plaque, knock it down and put something fantastic and new there.” Maitland disagrees: “It’s such an integral piece of a suite of buildings that speak to Canadian democracy. It’s across the road from Rideau Hall, down the street from Earnscliffe and related to the Parliament buildings down the river.” McTeer would like new construction “treated as a true national project to create a house that is an international showcase . . . perhaps as part of our 150th anniversary-year projects,” she writes in an email.

In the bloodless parlance of property values, the house is worth nothing, says Ottawa relator Marilyn Wilson, who specializes in Rockcliffe Park properties. She’d price 24 Sussex at $20 million: $16 million for land, with a $4-million premium “for location and provenance.” The house doesn’t add to the direct value of the property, says Wilson: “The home has not been maintained. This is the major way it differs from other homes of its kind.”

Obsession with dramatic before-and-after transformation sparked by HGTV, as well as the tear-down-and-build-bigger trend in Canadian cities, has informed discussion. Predictably, stars of reality TV have jumped into the fray: Mike Holmes announced he and his tool belt are at the ready on Facebook. Bryan Baeumler, host of Disaster DIY, revealed that he and eTalk host Ben Mulroney, son of Brian Mulroney, discussed creating a TV show around renovations to the house. Canadian corporations could supply products, Baeumler told the Toronto Star: “There’d certainly be sponsorship opportunities.” The NCC is reviewing plans for 24 Sussex, the Crown corporation recently said in a boilerplate statement that promised more information “in due course.” Until then, a house originally built as a gesture of love sits vacant.