How the wheels can fall off a political campaign

As Harper’s campaign endures bad news and reports of dissent, veterans of imploded campaigns explain how rot can set in

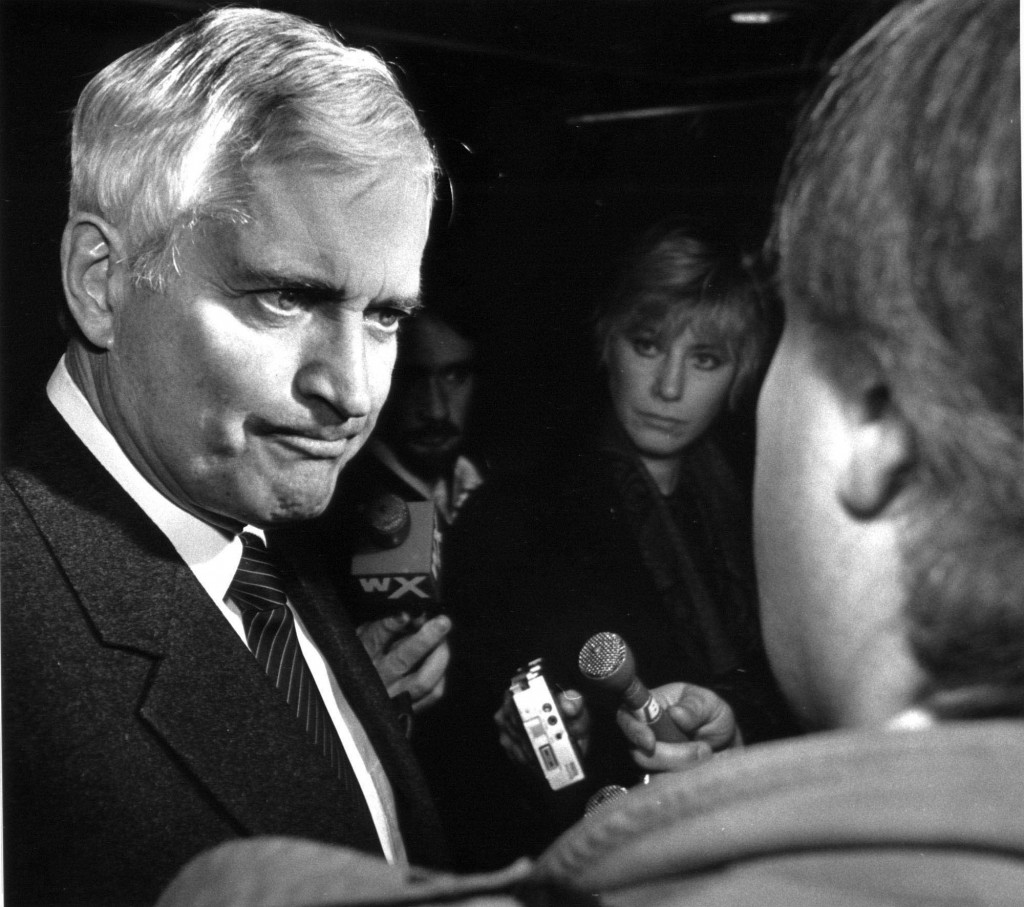

Conservative Leader Stephen Harper is seen backstage as he makes his way through the curtain during a campaign stop in Victoriaville, Que., Friday, September 11, 2015. (Adrian Wyld/CP)

Share

It starts out small. Then it quickly replicates and spreads. By the time it reaches the surface, the disease is often already terminal. All that’s left is the slow, sad march to the graveyard.

At least, that’s Allan Gregg’s take on what happens when a political campaign comes apart at the seams. “It’s like an internal cancer that starts growing and becomes harder and harder to stop,” he says. Gaffes and lapses in discipline lead to second-guessing, then infighting among staffers. Word of the turmoil leaks to the media and begins to overshadow your message. Acting out of fear and desperation, the leadership does a U-turn, or makes up new policy on the fly.

Gregg, a Toronto pundit and pollster, should know. Back in the fall of 1993, he was one of the guiding forces behind the campaign of Kim Campbell, an unnatural disaster that took the federal Progressive Conservatives from a majority government to just two seats in Parliament. (John Tory, now Toronto’s mayor, was another of the architects.) Campbell, who had taken over as prime minister from Brian Mulroney only a few months before, came into the election as the most popular politician in the country—her approval rating was the highest in 30 years. But a souring economy, coupled with a stumbling performance on the hustings—unemployment and the deficit would remain high until “the end of the century,” Campbell predicted, honestly and stupidly—erased all advantage.

What really sealed her fate, maintains Gregg, was her reaction to the controversy over a series of Conservative campaign ads that many thought mocked Jean Chrétien’s partially paralyzed face. Bowing to pressure, she had them pulled from the air, and the party’s support flat-lined. “Internally, the campaign just flew apart,” says Gregg. “And on a public level it made matters even worse, because it said that the Conservatives were venal and stupid.”

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

In recent days, there have been suggestions that Stephen Harper’s bid for a fourth term in power might similarly be coming unglued. Dogged by the Mike Duffy scandal, under attack for his reluctance to put out the welcome mat for Syrian refugees, and beset by bonehead candidates—including one who was caught on hidden camera urinating in a coffee cup—the Prime Minister has certainly known better weeks. His campaign manager, Jenni Byrne, has been punted from the tour, and an Aussie election guru brought in to try and reshape the message. Yet the latest slew of polls show no evidence of a nosedive. (According to one, an Ekos survey, released on Sept. 11, the Conservatives may even be back out in front at 31.8 per cent, versus 29.6 for the NDP, and 26.9 for the Liberals.) With an 11-week campaign—the lengthiest since 1872—perhaps regular rules don’t apply. Or maybe the rot just takes longer to set in.

Deb Grey, once, briefly, the leader of the Opposition, and a member of Parliament from 1989 to 2004, says she’s watching this campaign from afar, “all with mild amusement.” As an original Reformer, she lived through several tough elections as the party transitioned to the Canadian Alliance, then finally merged with the Progressive Conservatives. In 2000, under the new leadership of Stockwell Day—who kicked things off by driving up to his first news conference on a WaveRunner and suffered such indignities as a wildly popular Internet drive to have his first name changed to Doris—the Alliance took a beating from the Liberals. Even inside the biggest campaign bubble there’s still a palpable sense when the public turns against you, she says. “If a story has legs for more than three days, you know you’re in trouble,” says Grey. “But all you can do is get out there and try to put the wheels back on the bus. You have to stick to your message.” (The title of her political memoir is Never Retreat, Never Explain, Never Apologize.)

Of course, it’s not just leaders of the right who fall victim to changing tastes. Canadian history is littered with examples of once-popular politicians who stuck around a little too long, or arrived a bit late.

When John Turner finally wrested power away from Pierre Trudeau in 1984, he quickly called an election, trying to capitalize on an 11-point lead in the polls. But he got caught—not once, but twice—patting the derrières of female party members, and handed Brian Mulroney a sound bite for the ages on Liberal patronage appointment in a TV debate. (“You had an option sir . . . to say ‘No.’ ”) By the final weekend of the campaign, Turner was engaged in a desperate door-knocking blitz just to try and hold his own Vancouver riding. “The pathos of the story was not lost on the mob of reporters and TV crews who gathered for Turner’s last hurrah, following him door-to-door down otherwise tranquil residential streets, trampling every flower bed they encountered,” Greg Weston wrote in his 1988 book, Reign of Error. “The touching scene of a man with such high expectations of commanding a nation, reduced in the final hours to pleading for a single seat in the House of Commons.”

But perhaps the more pertinent example for the current Prime Minister might be the fate of one of his former lieutenants, Jim Prentice. The former federal minister of the environment appeared unbeatable when he took over as Alberta premier in late 2014, his popularity so high that the Opposition leader and eight of her MLAs crossed the floor to join him. But his trip to the polls just a few months later started with a campaign bus crash (literally) and ended as a train wreck. Rachel Notley’s NDP won an unprecedented majority, bringing almost 44 years of Conservative rule in the province to a whimpering end.

Are there lessons to be learned? It’s hard to say.

A request for an interview with Randy Dawson, Prentice’s chief strategist, was politely rebuffed. “Thanks for the note,” he wrote in an email. “But my therapist has conditioned me to forget it ever happened.”