Like father, like son. Only not always.

Like father, like son. Only not always.

Paul Chiasson/CP

Justin Trudeau invokes his father constantly, but he’s almost nothing like him. John Geddes explains

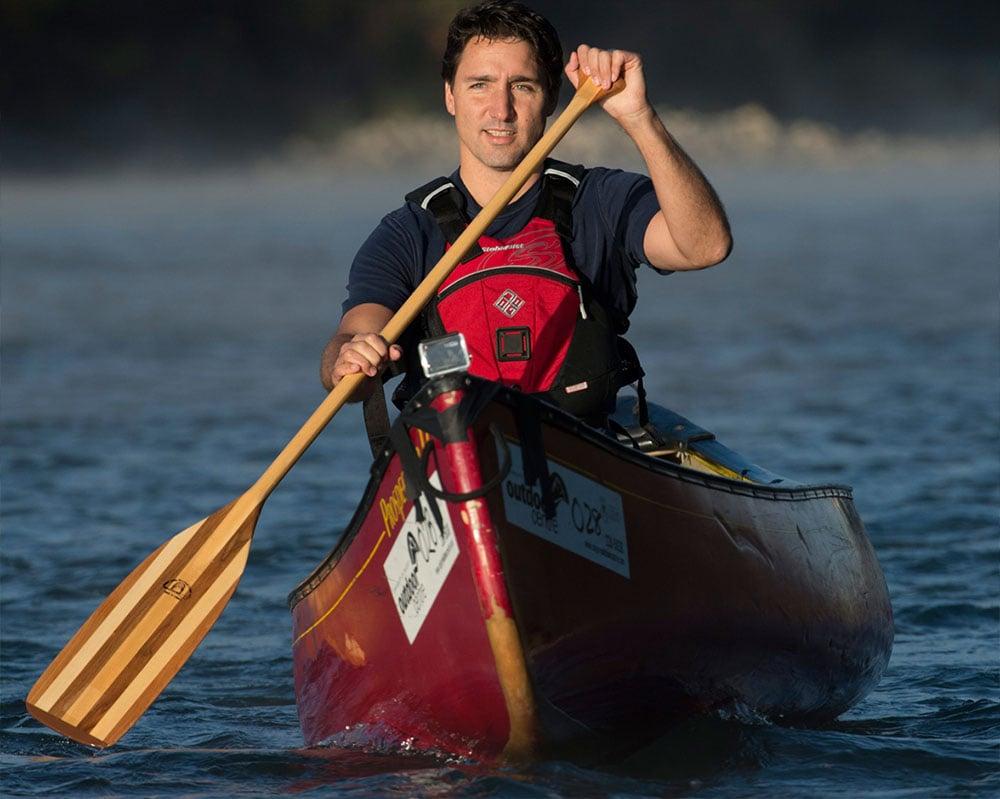

Much as Justin Trudeau likes to show off how he handles himself in the ring, his best punch couldn’t possibly sting a Conservative or New Democrat as sharply as the gentle dip of his paddle into the Bow River. To his adversaries, who tend to be acutely irritated by any reminder of Trudeau’s pedigree, his most galling photo op of the 2015 campaign so far had to be his solo canoe trip on the river that runs through Calgary.

It was the day of the leaders’ economic-policy debate staged in the oil capital, which meant Stephen Harper and Tom Mulcair would have to face their Liberal rival that evening with the widely disseminated image of him—plainly conjuring memories of his famous canoeing father emerging out of the river’s morning mist—fresh in their minds.

Drag the button in the centre of each image to see more of the two scenes.

Jonathan Hayward/CP and Doug Ball/CP

That sort of Trudeau-redux imagery drives his detractors crazy. Their hostility toward Pierre Elliott Trudeau runs deep. Harper has written about how he was drawn into Conservative politics in the first place by Alberta’s angry reaction to Trudeau’s 1980 National Energy Program. Mulcair has spoken repeatedly—most recently this week during the leaders’ debate on foreign policy—against the senior Trudeau’s use of the War Measures Act to suspend civil liberties in Quebec in 1970.

In fact, Mulcair’s latest bitter reference to the October Crisis set off Justin Trudeau’s most impassioned public defence of his dad to date. “Let me say very clearly: I am incredibly proud to be Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s son,” he fired back from the stage at Toronto’s Roy Thomson Hall. If he seemed primed to let loose about his father, he soon explained why. “It’s quite emotional for me to be able to talk about him, because it was 15 years ago tonight that he passed away, on Sept. 28, 2000.”

It would be a mistake, of course, to imagine this is all about pure critiques of Pierre Trudeau’s record, whether on the streets of Montreal in 1970 or in the oil patch a decade later. There’s something more viscerally personal at play here, too. Harper and Mulcair both pride themselves on having risen from modest backgrounds, and they overtly ask voters to identify with them on that basis. Justin Trudeau is the extreme opposite sort of politician: a scion.

Steve Russell/Toronto Star/Getty Images and Don Dutton/Toronto Public Library

Yet the son-of-Pierre role was a part he was unwilling to play until less than a decade ago. In the campaign-ready autobiography he published last year, Common Ground, Trudeau writes of his long “battle to convince myself and others that I was my own person.” Up until his involvement in the 2006 Liberal leadership race, he says his late father’s memory stood as “a reason for me to avoid entering the political arena.”

His reluctance evaporated as he backed Gerard Kennedy’s bid to lead the Liberals. Trudeau evidently discovered something about himself in the process. So did others who watched him. The way he clicked with delegates he attracted like groupies at the party’s Montreal leadership convention that year was a first glimpse of how Trudeau could parlay mere name recognition into a much rarer thing: the illusion that fleeting contact with a star is both welcomed and somehow meaningful. “I was surprised and enthused by the response I got from party members on the convention floor,” he writes.

The son-of-Pierre role was one Justin Trudeau was unwilling to play until less than a decade ago.

Kennedy lost, throwing his support to the eventual winner, Stéphane Dion. Trudeau switched to Dion, too. But the convention’s more lasting impact for the Liberal party has turned out to be Trudeau’s realization that politics was for him after all. Trudeauphiles see a certain irony in how it was the sweaty, up-close contact with convention-floor throngs that pulled Justin into politics: That was the part his father liked least. “Justin is closer to Bill Clinton than to Pierre Trudeau in the way he works crowds,” says historian John English, author of a two-volume biography of Pierre Trudeau, and himself a former Liberal MP. “He wades into them. He’s tactile and effusive. Pierre was great with a crowd of 5,000, but he wasn’t so good with a crowd of 50.”

Jeff McIntosh/CP and Fred Chartrand/CP

And Justin Trudeau isn’t at ease only with adoring mobs. A revealing amateur video shot last June shows him outside an event in Edmonton, patiently stating and re-stating his position with implacable protesters upset about his decision to have his Liberal MPs vote for Bill C-51, the controversial anti-terrorism law. Sen. Colin Kenny, who worked as a senior aide to Pierre Trudeau in the 1970s, says his boss wasn’t nearly as even-tempered with demonstrators. “There was always one cop in the crowd with Trudeau to take care of him, and by take care of him, I mean make sure he didn’t hit some guy,” Kenny says. “He got right out into crowds with guys shaking their fists right under his nose. The fear wasn’t so much they were going to harm Trudeau; it was Trudeau was going to harm them.”

The contrast between father and son extends from their public demeanours to their private relationships. New Brunswick Liberal MP Dominic LeBlanc is a lifelong friend of Justin Trudeau; LeBlanc’s father, the late governor general Roméo LeBlanc, was close to Pierre Trudeau. “I remember as a kid watching Pierre, who was my dad’s friend and his boss, and one of the few times you saw a lot of warmth and human affection from him was toward his three boys,” LeBlanc says.

Boris Spremo/Toronto Star via Getty Images and Christinne Muschi/REUTERS

The private Pierre Trudeau, at least in LeBlanc’s childhood memory, wasn’t so different from the public image of “this austere, sort of distant character.” Justin Trudeau is nothing like that. For instance, LeBlanc says he’ll call up friends on the weekend for no particular reason. “Just, ‘How are things going?’ ” he says. “I’m not sure the old man was like that.”

Trudeau attributes his approachability to the influence of his mother’s side of the family. “I’m definitely proud that I am more like my mom in many ways,” he told Maclean’s back in early 2012, when he was still framing his persona for a leadership bid. He also fondly remembers Margaret Trudeau’s father, James Sinclair, who had been an outgoing Liberal MP from Vancouver back in the 1950s. “For Grandpa, it was all about people,” he recalls, citing “Jimmy” as his role model for engaging with voters on the doorstep.

Close friends say Trudeau’s awareness of his father’s long shadow doesn’t translate into anxiety. In that morning paddle on the Bow River? Layers of image-crafting self-awareness.

Beyond self-consciously defining himself as his mother’s son, and emulating his late maternal grandfather’s retail-politicking style, Trudeau sometimes highlights a sharp contrast with his father on specific files. At the very outset of his 2012 leadership bid, he went to Calgary to vow never to try anything like the National Energy Program, the reviling of which remains a central tenet of Alberta pride.“I promise you I will never use the wealth of the West as a wedge to gain votes in the East,” Trudeau said.

Liberals often castigate Harper for concentrating power in the Prime Minister’s Office. But Trudeau, in a telling moment in a campaign interview with CBC’s Peter Mansbridge, said the trend toward too much PMO control predates the current Prime Minister. “Actually, it can be traced as far back as my father, who kicked it off in the first place,” Trudeau said, adding, “I actually quite like the symmetry of me being the one who ends that.”

Adrian Wyld/CP and Michael Evans/Liaison/Getty Images

In other respects, though, Justin Trudeau is eager to claim his inheritance. The Charter of Rights and Freedoms ranks high on that list. Asked about the backlash against his decision to vote for the Tories’ Bill C-51, Trudeau admitted to Maclean’s that he “made a strategic or a calculation error” by assuming Liberals would never be accused of undervaluing the individual rights his father’s Charter protects.

It was a case when he seemed to take the resonance of his surname too much for granted. At this week’s debate in Toronto, Trudeau said when he speaks of his father’s legacy, he means the Charter “first and foremost.” It can’t hurt that the Charter tops polls, along with universal health care, when Canadians are asked what unites the country. As well, Pierre Trudeau has ranked first in polls on the reputations of recent prime ministers, scoring particularly well in Ontario—just where his son now needs to forge an election breakthrough.

Close friends say Trudeau’s awareness of his father’s long shadow doesn’t translate into anxiety. Take the decision to stage that morning paddle on the Bow River. A senior Liberal strategist said Trudeau was, of course, fully aware of how it would evoke iconic images of his father in a canoe: “He said, ‘Look, I’ve spent my entire life in a canoe. I’m an excellent canoeist. It would be something I would do to relax on a stressful day.’ ” There are layers of image-crafting self-awareness in that calculation: It will look like my dad, but it’s the sort of thing I might do anyway, so I get to do it.

Sean Kilpatrick/CP and Peter Bregg/CP

Casual observers sometimes presume differences between Trudeau père et fils that insiders doubt are real. For instance, there’s the assumption that Pierre Trudeau’s aloof quality must have translated into solitary decision-making. In fact, Kenny says he was never a one-man show behind the scenes. “He was absolutely inclusive,” Kenny says, recounting how Trudeau would almost obsessively canvass his cabinet for input on key decisions. “I never heard anybody say that in their area of responsibility, he wasn’t attentive to them.”

Justin Trudeau says he witnessed and internalized that consultative side, so at odds with his father’s detached air. In Common Ground, he writes of travelling as a child with his father on official trips abroad, and noting his attentiveness to advisers’ opinions. “He would rarely discuss his own views in any detail until everyone else had had their say, which was in contrast with his image as an almost autocratic decision-maker,” Trudeau writes.

From some angles, Pierre Trudeau had, compared with his eldest son, far deeper experience in public life before wading into the political fray. He had long been a prominent Quebec intellectual and activist before being recruited by the federal Liberals in 1965 as a star candidate. The safe seat of Mount Royal was cleared for him through the personal intervention of then-prime minister Lester Pearson.

Justin Trudeau was a schoolteacher and a well-paid public speaker before making the leap into politics. He attained nothing approaching his father’s credentials as a serious voice in public affairs. But there are other sorts of experience. He campaigned energetically for Kennedy, then travelled the country, meeting with young voters as part of a Liberal “renewal commission.”

Darryl Dyck/CP and Boris Spremo/Getty Images

And there are other ways of being tested. Under Dion’s leadership, he wasn’t offered a choice seat. He had to fight for the Liberal nomination in Montreal’s Papineau riding, then knock off a strong Bloc Québécois incumbent in the 2008 election. As a rookie MP, he wasn’t assigned a top critic’s role. Instead, he became better known for his massive Twitter following—giving thousands a sense of direct access to him that would have made his father recoil. His triumphant leadership campaign in 2013 amounted to a concerted membership drive.

Along the way, he came to fault his party for its long neglect of grassroots connections. And guess whom he blames for allowing that drift toward a disconnection from ordinary Canadians to begin? “It probably started during my own father’s leadership,” he writes in Common Ground. “He (to be charitable) perhaps spent less time nurturing the grassroots of the party than he might have.”

Looking for commonalities and contrasts between father and son is a game inveterate Trudeau-watchers won’t give up any time soon. Trudeau’s telling allusions to his father’s myth and memory suggest he’s at ease with the comparison.

Even Pierre Trudeau loyalists tend to credit Justin with possessing a better grasp of his party than his father had acquired before he was elected prime minister in 1968. Pierre didn’t turn his formidable intelligence to mundane party organization and campaign planning matters until his 1968 majority was shrunk to a minority in the 1972 election. “Pierre Trudeau didn’t understand how the politics of the party worked until he got thumped in ’72,” Kenny says. “From ’72 to ’74, he took a crash course in how all this comes together. Justin already has a background and a knowledge of it.”

David Cooper/Getty Images and Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The 1972 scare prompted Trudeau to turn to strategists Keith Davey and Jim Coutts. Davey is credited with instilling the doctrine that the Liberal party must run from the left, allowing the NDP the minimum room to carve off progressive-minded voters. In the current campaign, Trudeau is campaigning to the left of the NDP by proposing to run deficits, hike taxes on high-income earners, and not buy F-35 fighter jets. His top advisers say these are sound policies, not tactical ploys to outflank Mulcair. Still, English suspects the current campaign’s left-tilting elements show how akin the new Trudeau team’s mindset is to that of the post-1972 Trudeau crew. “I think it’s instinctive,” he says.

Looking for commonalities and contrasts between father and son is a game inveterate Trudeau-watchers won’t give up any time soon. As this race enters its final leg, Trudeau’s telling allusions to his father’s myth and memory—a canoeing photo op here, a critical remark there—suggest he’s at ease with the comparison. If he has never presented himself as a thinker on his father’s level, he may be staking a claim to being a better-grounded campaigner. On that score, the crucial test isn’t how he stacks up against burnished memories of the ’60s, ’70s and early ’80s, but how he fares on Oct. 19, 2015.

Published October 2, 2015

Related