Lloyd Axworthy: A politician who thinks globally, and acts locally

Our profile of Lloyd Axworthy, who we’re honouring with Maclean’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award

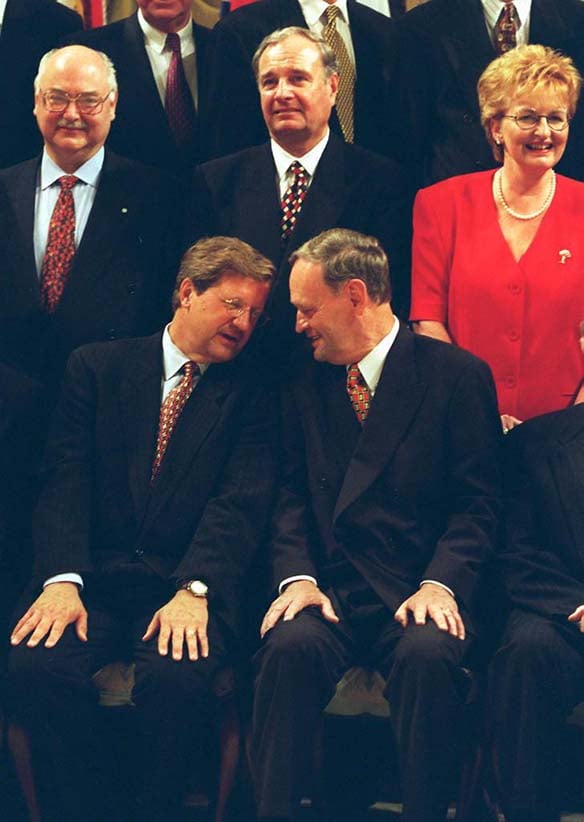

Dr Lloyd Axworthy. (Photograph by Thomas Fricke)

Share

Every year for the last six years, as part of our Parliamentarians of the Year awards—or, in the first year of a new Parliament, a “Welcome to the Hill” event—Maclean’s has recognized a former parliamentarian for their impact on Canadian politics. These prestigious lifetime achievement awards have been given to such vital figures as Flora MacDonald, Canada’s first female foreign affairs minister, and Peter Milliken, whose historic term as Speaker of the House made him a beloved parliamentarian. In 2016, Maclean’s is honouring Lloyd Axworthy, the influential international affairs leader who served in the cabinets of three prime ministers.

Lloyd Axworthy’s story of how he was first elected to Parliament is pure Winnipeg. At the start of the 1979 campaign, he quit as a Liberal member of Manitoba’s legislature to run for a federal seat. Joe Clark’s Conservatives would win the election nationally, but Axworthy managed, against his own party’s expectations, to upset Sid Spivak, a former provincial Tory leader, in the Winnipeg–Fort Garry riding. The famously flood-prone Red River saved him, Axworthy claims, by cresting at just the right moment. “I announced I was going to stop campaigning and go work on the dykes,” he recalls. “Got my picture in the papers and kind of slipped through by about 600 votes.”

In the two-decade run on Parliament Hill that followed, Axworthy’s bond with his home city never weakened. He served as a key cabinet minister, first under Pierre Trudeau and later, after the Liberals weathered a long stretch in opposition, under Jean Chrétien. His signature national and international impact came when he recast Canada’s approach to the world under the banner “human security” as Chrétien’s foreign minister. Still, in his post-political career, after he exited the federal scene in 2000, Axworthy returned to his roots, spending 10 years spearheading an impressive expansion and transformation of the University of Winnipeg.

The most striking feature of Axworthy’s career has been that counterbalance between an expansively international outlook and intensely local loyalties. In an interview before Maclean’s honoured him on Tuesday as the 2016 winner of our Lifetime Achievement Award for a former parliamentarian, he suggested his postwar upbringing in Winnipeg’s storied North End, a magnet for immigrants, especially from Eastern Europe, both rooted him and made him acutely aware of the wider world. “Being a WASP kid, that was the ultimate minority,” he says. “I became very conscious quite early of different languages and food and girls and everything else.”

Axworthy was born in North Battleford, Sask., in 1939. His father’s family had homesteaded in the province and his mother’s ran small stores in towns like Melville and Yorkton. While his father was off fighting in the Second World War, his mother moved closer to family in Winnipeg. Although he was too young to remember details of the war years, Axworthy says the feel of that time—including urgent conversations about casualty lists among the adults at the kitchen table—stayed with him as “a wartime child.”

The United Church, and the activist “social gospel” tradition so prevalent in Winnipeg, was central to his parents’ lives. Through the church, Axworthy participated in model youth parliaments in his early teens, and he might well have been drawn to the social-democratic Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, precursor to the NDP, had it not been for a Grade 11 history class outing to hear a visiting speaker. Lester B. Pearson, a Liberal star after winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1957 for his role in settling the Suez Crisis, came to speak at Winnipeg’s Civic Auditorium. To Axworthy, Pearson at first seemed unimpressive—“a sort of roly-poly guy with a bow tie and a bit of a lisp”— but his Liberalism captured the teenager’s imagination. “I walked out of that place really understanding for the first time who I was in terms of a political scene,” he says.

There was no question that he would attend the local United College, which was closely aligned with his family’s church. It was, he says, “a humming place,” where he started to think about a political career. He imagined studying law first, until a history professor suggested he try for a scholarship to Princeton University. He had to borrow a jacket and shirt suitable for his interview with the visiting American scholarship selection panel. “These were the classic Ivy League guys in the tweed suits and button-downs,” he says. “The only thing I couldn’t replace were the old khaki chinos I wore every day. So I’m sitting down in front of these Ivy Leaguers, and the first question was, ‘Tell us why you’d like to go to Princeton.’ And in a very suave manner, I threw one knee over the other, and my knee came out of my pants.”

Related: John Geddes in conversation with Lloyd Axworthy on his long, fascinating career

He won the scholarship and went on to earn his M.A. and Ph.D. at Princeton, where he was active in the roiling 1960s civil rights movement on campus. He returned to Winnipeg to teach, notably as director of a new Institute of Urban Affairs at the University of Winnipeg, as United College had been renamed. But he was itching to break into politics. He worked for John Turner in the epic 1968 federal Liberal leadership contest won by Pierre Trudeau, then secured a seat in Manitoba’s legislature in 1973.

His leap into federal politics in 1979 came in time for the climactic last chapter of the Pierre Trudeau era in Ottawa, after Trudeau ousted Clark’s short-lived Tory minority in the 1980 election. As one of only two Liberal MPs west of Ontario, the Winnipeg rookie was assured a cabinet job. Trudeau made him employment and immigration minister, and Axworthy took on the resettlement of Vietnamese boat people, begun under the Conservatives, which plunged him into international files.

From 1984 to 1993, Axworthy, like the rest of the Liberal party, waited out the Mulroney era of Conservative rule. When Chrétien won the 1993 election, Axworthy looked like a probable foreign minister, but Chrétien had another task in mind—another stint as employment and immigration minister, this time assigned to overhaul Unemployment Insurance. By then, Axworthy was a pillar of the Liberal left, so Chrétien thought he might be able sell reforms that progressives were bound to see as hard-hearted.

Indeed, Axworthy set out to make it more difficult for seasonal workers to routinely quality for benefits year after year. “We said, no, it wasn’t going to be that easy, but we’re going to provide work supplements, employment incentives,” he says. To this day, Axworthy regrets that the changes he tried to put in place were subsequently rolled back, largely by his own party, and mainly because of a backlash in the Atlantic provinces.

But he moved on. In 1996, Chrétien finally made him foreign minister. In those post-Cold War years, foreign policy was being fundamentally reassessed everywhere. Axworthy pushed for Canada to reframe its approach around “human security.” The basic idea was to be guided not by national interest but by the imperative to protect people. A powerful spur, he says, was the 1995 massacre of more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslims in Srebrenica by Bosnian Serb forces. Under the new doctrine, Axworthy was a driving force behind the Ottawa Treaty banning anti-personnel land mines, and an outspoken advocate of the UN’s adoption of the so-called “responsibility to protect” principle, which calls for international interventions in countries where people are threatened by atrocities or genocide.

When he retired from politics in 2000, Axworthy became head of the University of British Columbia’s Liu Institute for Global Issues, and seemed destined to remain a foreign-policy specialist. But home beckoned. He was appointed president of the University of Winnipeg in 2004. So began his decade-long drive to expand his alma mater, raising hundreds of millions for new buildings on its downtown campus. He pushed the university to better serve Winnipeg’s inner-city Indigenous and immigrant communities, launching programs to prepare high school students for higher education. “We’ve proven that you can start with a 15-year-old kid, off the street, bring them into a model school, have them go on to university, and get 80s in their courses,” he says. “A university seriously doing outreach in the community can open up a big, big window for Aboriginal and new Canadian kids.”

He left the university in 2014, taking on a new role as chair of Cuso International, where he guides the organization—long active in overseas development—in a new thrust aimed at helping First Nations in North America. For Axworthy, at 76, the international and the local continue to keep unusually close company.