Thomas Mulcair’s Clarity problem

Why, in an otherwise strong debate, did the NDP leader tread into the dangerous quicksand of Quebec separatism?

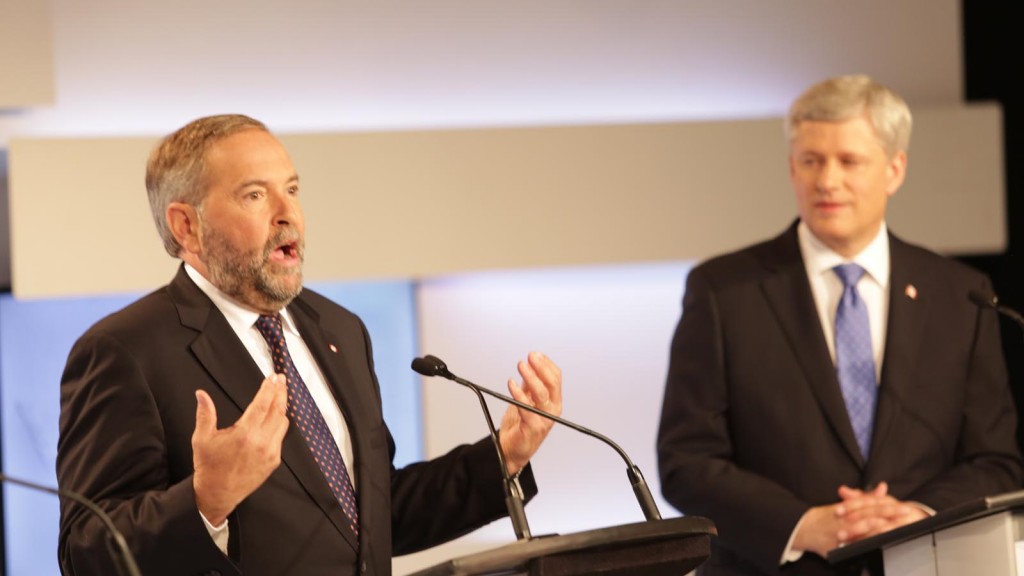

NDP LEADER THOMAS MULCAIR SPEAKS DURING THE MACLEAN’S LEADERS DEBATE, TORONTO, ON, AUGUST 6TH, 2015. (DILLAN COOLS/MACLEAN’S)

Share

At about the midpoint of last night’s debate, during an otherwise necessary chat about the state of democratic institutions, things veered into a constitutional abstraction of the sort that has obsessed this country’s political class for a half century. It lasted about five minutes and was prompted by Justin Trudeau, who looks younger than his 43 years but, at that moment at least, could have passed for pater Pierre Elliott circa 1968, shaking his fists at the evil Quebec separatists in our midst.

“One of the things that really frustrates a lot of people is when they see politicians pander, when they say one thing in one part of the country and a different thing in another part of the country. One of the things that unfortunately Mr. Mulcair has been doing quite regularly is talking in French about his desire to repeal the Clarity Act, to make it easier for those who want to break up this country to actually do so. And in doing so, he is actually disagreeing with the Supreme Court judgment that said one vote is not enough to break up the country.”

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

The Clarity Act was wrought by Jean Chrétien’s government in 2000 to try and address the question born in 1995’s Quebec referendum, which the No side won by all of 54,288 votes: would it have been enough to separate the country had the Yes side won by as many (or fewer) votes? The Supreme Court’s answer was no: a province would need a “clear majority.” Except no one defined what, exactly, constituted this clear majority. The resulting lack of clarity has obsessed Canada’s political class and legions of its journalists ever since.

Three things usually happen whenever this issue is brought up in a federal campaign. First, chest puffed, each leader will say what good Canadians they are. Then the others will say how irrelevant it is to talk about separatism, because Quebec’s sovereignty movement is stuck somewhere between cryogenic sleep and outright death. Finally, they do exactly that—talk about an apparently irrelevant issue. For over 50 years, it’s been our political quicksand: impossible to avoid, and even harder to escape.

True to form and slave to tradition, NDP Leader Tom Mulcair gamely responded, “I’ve fought for Canada my whole life,” Mulcair said. Then: “The only two people I know in Canada who are anxious to start talking about separatism again are Justin Trudeau and Gilles Duceppe.”

And then, Mulcair himself became very anxious to discuss separatism. “Mr. Trudeau has an obligation, if he wants to talk about this subject, to come clean with Canadians. What’s his number? What is your number, Mr. Trudeau?” (There isn’t one. As Mulcair well knows, the Clarity Act is decidedly unclear on this.)

By the by, that Trudeau blunted Mulcair’s staged fury with his answer—”Nine. My number is nine. Nine Supreme Court justices said one vote is not enough to break up this country, and yet that is Mr. Mulcair’s position,” Trudeau said—is the NDP’s own fault. Just before the debate, the Huffington’s Post’s Althia Raj published a piece in which she quoted a senior NDP source saying Trudeau should expect Mulcair to attack him on the Clarity Act question. This effectively gave the Liberals two months to come up with the pithy answer we saw last night.

Political points aside, both Trudeau and Mulcair would do well to look at Quebec today, if only to see how misplaced that obsession over sovereignty has become. Since the Clarity Act became law, the Parti Québécois has been in power for less than five of the last 15 years; the one time the party won an election, in 2012, was out of a general state of fury toward Jean Charest’s Liberals—and even then, the PQ couldn’t muster a majority. In 2014, party leader Pauline Marois and company couldn’t even utter the word “referendum,” for fear of losing the election. Instead, the PQ ran on its “Quebec values charter,” sovereignty’s grotesque surrogate, in which the party attempted to stoke the nationalist flame by scapegoating religious minorities. It lost the election regardless.

Pierre Trudeau had plenty of enemies at which to shake his fist in 1968, but he, like so many of them, is no longer with us. While Quebec separatism isn’t dead, the issue hardly seems to deserve airtime in a national debate. “You’re trying to throw gasoline on a fire that isn’t even burning,” as Prime Minister Stephen Harper nicely put it. Of course, this was right after he accused Mulcair of trying to placate “the separatist elements within the NDP.”

There may well be a few separatists lurking about in the NDP, just as there is a whack of former Bloquistes in the Conservative party. The “separatist elements” are actually Quebec voters who migrated massively to the NDP in 2011; the NDP and the Bloc Québécois are ideologically similar, save for the whole Quebec separation thing. For most soft nationalists, a repeal of the Clarity Act would be a big enough fig leaf to vote for a federalist party. Hence Mulcair’s promise, made in French, to do just this.

Mulcair’s otherwise strong debate was hampered somewhat by the weight of high expectations. Mulcair should have kept his focus on Harper, and he lent Trudeau legitimacy just by engaging the Liberal leader. Mulcair’s plan to abolish the Senate, meanwhile, looks more and more like an electoral prop. He knows full well Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard is steadfast against such a thing—even if, as Mulcair awkwardly noted, he is good friends with Couillard.

Mulcair has to retain his Quebec beachhead of 54 seats in the coming election. Being sidelined by Trudeau, and ultimately falling into the political quicksand of sovereigntist-baiting, is a digression he can hardly afford.