One thing Justin Trudeau and Stephen Harper agree on

Economic growth helps balance budgets, writes Mike Moffatt

Centre Block’s Peace Tower is shown through the gates of Parliament Hill as Finance Minister Jim Flaherty prepares to table the budget on Parliament Hill in Ottawa on Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2014. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Justin Tang

Share

When Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau made comments about the budget being able to balance itself if economic growth were higher, I paid little attention, as Canada’s budget deficit is relatively small and I have heard many others make this claim.

As such, I was surprised to see these comments form the basis of a recent Conservative Party TV commercial. In my view, it is an unusual point of criticism, as the idea that a government’s budgetary balance depends on economic growth is widely known by economists, and politicians such as Jim Flaherty, Ronald Reagan and even Steven Harper routinely point out how economic growth is crucial to balancing a government’s budget.

The 2014 Budget itself makes this connection, with page 287 noting that personal income tax revenues, corporate tax revenues and GST revenues rise and fall with the level of economic growth. Political parties, when releasing their economic plans and forecasts often make use of this relationship. During the 1993 election, the Reform Party ran on a “Zero in Three” plan that would have a Reform Party government balance the federal budget after three years. Their plan to balance the budget involved 18 billion dollars in spending cuts, along with $16 billion in additional revenue gained from economic growth.

In a lengthy piece by Claudia Cattaneo for the Calgary Herald (May 9, 1993) the party’s then economic advisor, Stephen Harper, argued the significant deficit reductions from the plan’s economic growth projections were reasonable:

The party says its growth rate forecast is conservative when you consider that the annual growth rate over the past 10 years was 2.5 per cent, including recessionary periods. The higher rate for the three-year period is justified because the economy is now lagging behind and is on the verge of playing catch-up as Canada enters a new growth cycle, said economic policy adviser Stephen Harper, who came up with the projections. Harper is the party’s candidate for Calgary West.

The current government has also made similar claims in the past. An October 1, 2010 Toronto Star article gave Finance Minister Jim Flaherty’s views on what it will take to balance the budget (my emphasis added):

Flaherty brushed off suggestions that reducing Ottawa’s planned EI take could make it harder to curb the deficit, saying it won’t matter if the economy performs well enough.

“If you look out into the medium term, the effect is okay so that we can balance the budget in the medium term—and that is around 2014-2015 or so, depending on the degree of economic growth,” Flaherty said.

Flaherty saw this relationship between GDP growth and government revenues first-hand when he was Ontario’s Finance Minister, during a time when the government’s budgetary position eroded due to slower-than-anticipated economic growth. A Feburary 28, 2002 National Post article quotes the then Ontario Finance Minister:

“The predicted economic growth is 1.3%, which is significantly lower than anticipated, so that puts great pressure on the finances of the government of Ontario in the next year,” Mr. Flaherty said after his committee appearance.

Given the recent TV advertisements, I am uncertain what the government’s current position on economic growth and the budgetary balance is. The Reform Party of 1993 recognized that the deficit was so bad that economic growth alone would not be enough to balance the budget. Others need to be dragged into the realization that there is a structural deficit. Ronald Reagan spent much of 1981 and 1982 claiming that economic growth would balance the budget. By late 1982 he was forced to change his tune, telling Time magazine that “I don’t suppose that I had anticipated that there is… a structural part of the deficit that has nothing to do with the recession.”

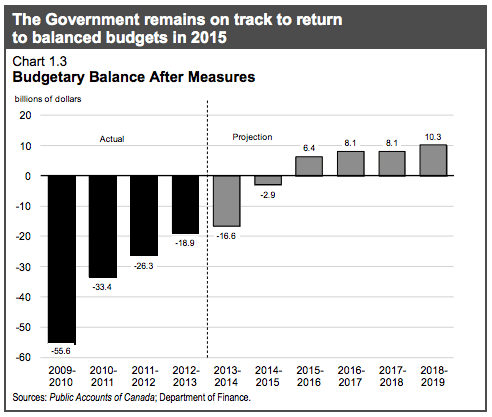

In my view, we should not believe the federal government is in a similar position to 1993 or to the U.S. government in 1981-82. It is difficult to argue that the federal government of 2014 has a structural deficit—that is, a deficit that will still exist when the economy is performing at potential. Page 287 of the 2014 Budget has an estimate that a 1-percentage point decrease in GDP growth would reduce “the budgetary balance by $3.7 billion in the first year, $4.5 billion in the second year and $6.0 billion by the fifth year.” Increases in GDP have the opposite effect, so those are the magnitudes that we should be looking at. The budget gives an estimate deficit of only 2.9 billion in 2014-2015 (page 10), so it is very reasonable to suggest that somewhat faster economic growth would fill this gap.

In the current Canadian context, Justin Trudeau’s statement was reasonable to the point of being obvious. I am puzzled why his comments have received so much attention.