Plucking the wings off a visitor from fairyland

On Day 7 of Mike Duffy’s trial, a lawyer drags an Upper Chamber pixie down to earth

Suspended Senator Mike Duffy arrives at the courthouse in Ottawa April 13, 2015. Duffy, a former ally of Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper, is on trial for fraud and bribery in a high-profile case that could hurt the ruling Conservatives’ chances of winning an election this October. Chris Wattie/Reuters

Share

It would be as painful to watch a barrister pick apart a pixie on the topic of gravity—that mysterious force, found only in this human world, dragging her earthbound.

In the Senate of Canada, this pixie has wings. Administrative fairy dust heals each breach in time’s fabric. And a senator’s signature is magic—black ink animating all things.

The trouble for her was that here, in court, she was being asked real-world questions, maybe for the first time.

The senator with the magic ink is Mike Duffy, who is on trial in Courtroom 33, in Ottawa’s Elgin Street courthouse, for 31 fraud, breach of trust and bribery-related charges.

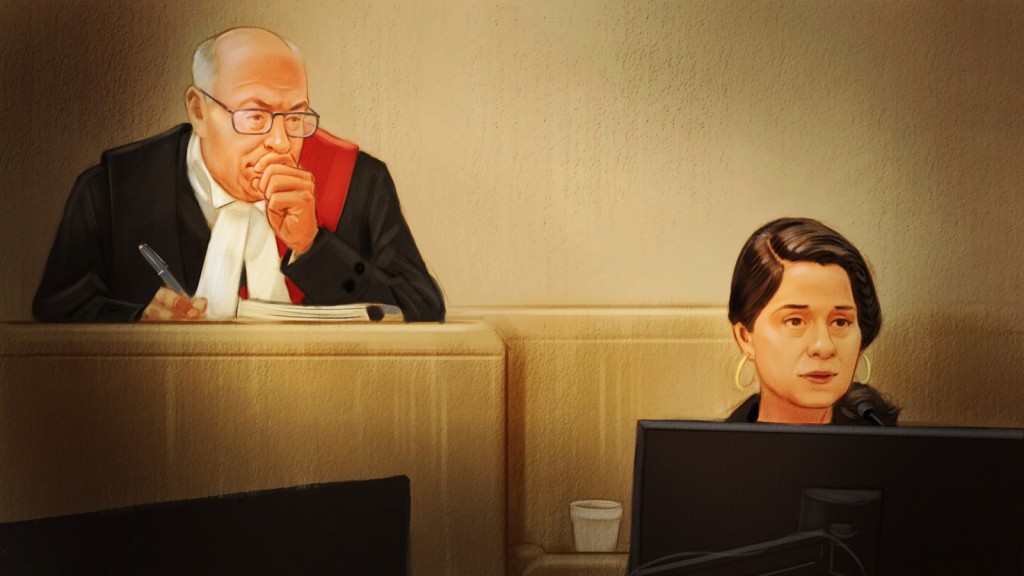

And that visitor from fairy land was Sonia Makhlouf, a Senate human resources director, in the witness box for her third consecutive day.

By this afternoon, all that gravity had taken its toll. Makhlouf looked shattered as court broke by news she was being called again tomorrow, for the Crown’s re-examination.

She’s been drained by these proceedings, and by defence lawyer Donald Bayne’s exacting questions. She answered him as the day wore on with an increasingly pained expression, the kind that’s unique to public servants who find themselves actually forced to deal with the public.

Bayne was not put off. There’s something almost Sherlockian in the way he casts his eye about the room, shrugs one shoulder, then hunches over a podium—he has two of them set up, weighted down with books—and he presses issues with an intensity and doggedness that makes the gallery squirm.

It made Makhlouf squirm, that’s for sure. Early into her morning of testimony, as Bayne dug into the topic of an arcane bit of Senate paperwork, it felt like she would dissolve.

Suddenly she asked for a break.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Mike Duffy”]

No one watching envied her. As anyone who’s been through examination for discovery or sat in a witness box will tell you, the experience opens up vast, unexplored continents of self-doubt. And Bayne was probing some uncomfortable truths about the Senate and Makhlouf’s job.

He led her through a series of Duffy contracts approved by HR. The contract requests contained spotty information on the services the Senator was seeking, while the invoices that rolled in later often arrived with even fewer details than that. It was sometimes difficult to tell when the work had begun. Sometimes the work was almost already done by the time the contract got signed. No one appears to have taken the trouble to gauge the quality of that work, or even if it had happened at all.

Makhlouf spent four years in this job vetting contract requests, which basically amounted, apparently, to ensuring each field in the form is filled. And she’s spent 18 years as a Senate staffer overall. You wouldn’t know it. At times it appeared she did not know the rules of the house, and she frequently appeared puzzled by the question of why that matters.

We shouldn’t judge her based on her performance in court. She was painfully nervous in the witness box—clearly she would rather have been anywhere else.

But the fact is too that this does matter: the allegations here say Duffy used Senate contracts to distribute public funds among his buddies, in return for very little.

Bayne’s gambit has been to show just how broad the notion of Senate business remained during the period at issue in the trial, just how much weight Duffy’s discretion and signature carried in pulling cash, just how vague the rules got. Nor did anyone check on whether what Duffy or any other senator purchased was worth the money.

In one case Bayne highlighted, in which a contract was approved after the services got rendered—contrary to a clear rule, this time—Makhlouf backdated the paperwork.

Bayne agreed she had little choice: the Senate, he suggested, was hamstrung by turf wars between the HR and finance directorates, and struggling with outmoded practices. “We crafted administrative solutions to administrative irregularities,” Bayne said, paraphrasing the philosophy of the joint, and “administratively irregular” became a kind of motif in today’s cross-examination.“The guidelines and policies may be one thing, but the practices, in fact, are another, right?” said Bayne, putting it to Makhlouf. “Yes,” she said.

That’s what fairy dust looks like when it’s sprinkled in the Senate: an administrative solution. A fix to what’s real.

Court reporter Nicholas Köhler on the Duffy trial:

- Day one: Mike Duffy talked for a living. On Monday, he spoke six words.

- Day two: Kafka meets Frank Capra in Courtroom 33

- Day three: The PM is just a girl he used to know

- Day four: The subject of honour and the genie of Cavendish

- Day five: Mike Duffy, patron saint of the good ol’ days

- Day six: Oversight in Canada’s Senate? There’s no such thing.