The real problem with politicians’ vacation time? Not enough of it.

Politicians—and their staffers—are starting to skip vacations to do more work. Is that really a good thing?

Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil, left, announces that Halifax will be a 2017 Tall Ships Regatta venue coinciding with the province’s Canada 150 celebration during a press conference on the waterfront in Halifax on Friday, May 13, 2016. (Darren Calabrese/CP)

Share

Nova Scotia Premier Stephen McNeil took no vacation this summer—not a single day. “It’s not my nature to ever get to zero,” he says, having spent his months traversing the province. He isn’t even sure how much vacation time is stipulated in his contract. If he did take time off, he says, “I’d certainly be in contact with my office.”

Like McNeil, most Canadian politicians are working hard and hardly resting. Newfoundland and Labrador Premier Dwight Ball took just three days between June and August. “He does not stop,” says Michelle Cannizzaro, manager of media relations for the Premier’s Office. “This is definitely a pace above and beyond the rest.”

Yukon Premier Darrell Pasloski vacationed for only two days—to see the Tragically Hip perform in Vancouver, though he may take a couple more days before Labour Day to go hunting. His neighbouring premier in the Northwest Territories, Premier Bob McLeod, left the office for six days to take his grandson to hockey camp. McLeod worked on Canada Day and on National Aboriginal Day, another statutory holiday in the territories.

It’s an ethic born of “vacation shaming,” a common pastime for the public and media, which cry “off with their heads” whenever politicians take time off. When Justin Trudeau spent three weeks away from work this summer, split between Ottawa and British Columbia, social media went wild with photos of him “photo bombing” a beach picture in his swim trunks in Tofino—along with criticisms that he was shirking his duties amid the threat of a real bombing in Strathroy, Ont. “Prime Minister Justin Trudeau didn’t even emerge from his extended vacation to assure Canadians he was monitoring the situation,” wrote one radio show host, Andrew Lawton, in the Toronto Sun. “Apparently his vacation came first.” The federal Conservative party website juxtaposed Trudeau’s vacation photo next to statistics of job losses in July.

Some of the shaming may have merit. Eyebrows rose when Trudeau took the day off during a diplomatic trip to Japan for the G20 Summit to celebrate his wedding anniversary, and eyebrows furrowed when Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister was shown to have spent 240 days at his home in Costa Rica over 3½ years in office. Pallister, along with Alberta Premier Rachel Notley and Prince Edward Island Premier Wade MacLauchlan, did not respond to requests for information about their vacation time this summer. Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne’s office says, “We do not directly comment on the premier’s private appointments or private time with family and loved ones.”

But vacation shaming may be leading to vacation skipping, as politicians—and their staffers—opt out of holidays entirely. “There’s a misconception that government is a cushy job,” says Cannizzaro. “There are people here that have three, four children. They don’t leave the office until six, seven. They’re heroes.” Cannizzaro is taking no summer vacation herself. “I think it’s a necessity to be working constantly,” she says. “I don’t mind the long hours. I think the province deserves it.”

Human-resources experts question the ethics of the extreme work ethic. “At some point, you’re going to crack,” says Cissy Pau, a human-resources consultant based in Vancouver. She says politicians are increasingly using their benefit plans for stress-related health problems including high cholesterol, low energy and insomnia. “They’re not doing themselves or their constituents justice,” she says.

Vacation skipping is induced by people’s own work addictions as much as by fear of public scrutiny. Twenty-six per cent of Canadians, politicians or otherwise, don’t use their allotted vacation time, according to a 2014 survey by Robert Half, a consultancy that conducts industry research in the States. Canadians tend to declare they’re too busy. “You can’t use ‘busy’ as an excuse,” says Pau, noting that higher performers just get assigned more work. “The more you do, the more you get,” she says.

Over-workers also justify skipping vacation by saying they love their jobs. Yet, Pau wonders, “how do you put some boundaries around that?” In politics, she says this workaholic spirit might turn off the next generation of politicians because Millennials will seek more time off. “If you have a suck-ya-in, burn-ya-out way of staffing, you’re not going to have high retention,” she warns.

Solutions include forcing politicians to take their vacation and “cross-training” staff to check their messages during their absence. Some workplaces have a “blackout period” for vacation time—the busiest times of year when employees cannot take time off—and encourage holidays at other times of year. “It’s essential for human beings that we have time away from constant doing,” says Steven Hick, a retired social work professor at Carleton University. He now leads mindfulness-based stress reduction programs in Ottawa, including for people in politics. “It makes them better leaders because they’re more present. When someone’s talking, they’re actually listening.”

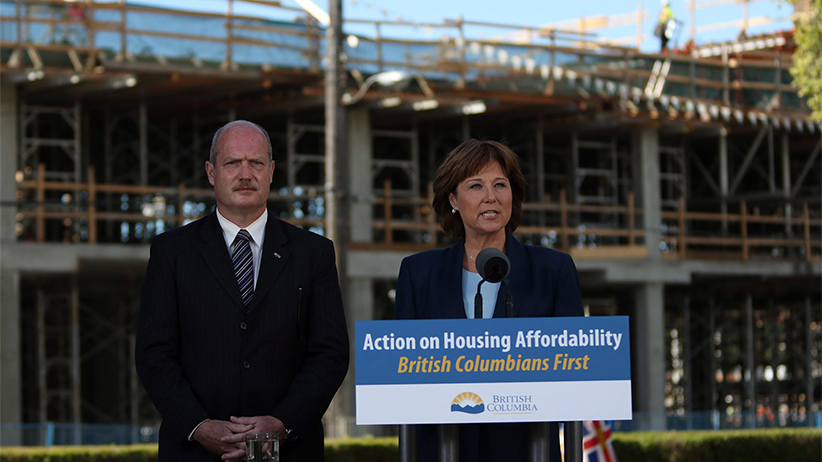

Listed from most to least rested this summer, British Columbia’s Premier Christy Clark took approximately three weeks; Nunavut Premier Peter Taptuna took approximately two, and Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard also took two weeks, though he was sending emails and reading reports while he was gone fishing. In New Brunswick, Premier Brian Gallant left the office for one week, which he spent in the province with his family and chocolate labrador, Blaze.

McNeil will take time off in September after a trade mission to China, spending it with his two twentysomething children, but he will still be on call. Despite his agenda, McNeil has actually had fun working these past three months, attending community events including a lawn-bowling championship, a 100-year-old woman’s birthday party, a tour of the Bluenose sailboat and an axe-throwing arena at a brewery. “Why would I ever want to leave this place in the summer?” he wonders. He doesn’t plan to slow down for the rest of his term, which lasts until October 2017. “It’s a job you don’t get to do forever,” he says. “You work as hard as you can in that window.”