The Yes minister: Can Steven Blaney stand up to the boss he loves?

Steven Blaney rose to the top with his fierce loyalty to Harper. Now, as head of Public Safety, will he push back?

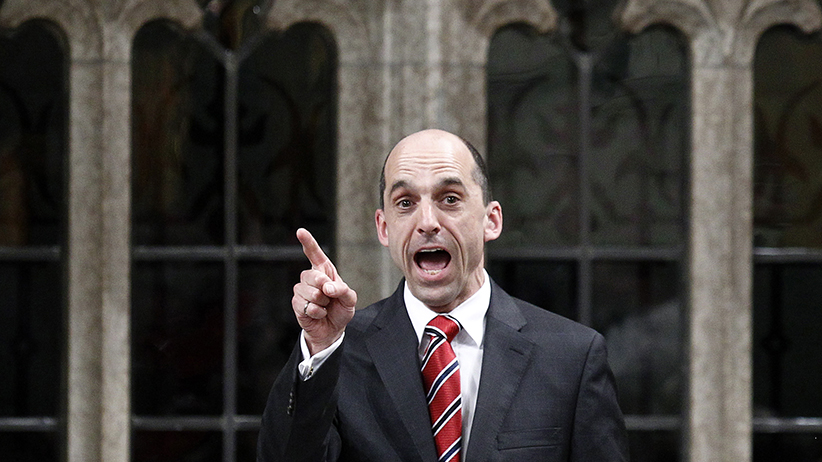

Canada’s Veterans Affairs Minister Steven Blaney speaks during Question Period in the House of Commons on Parliament Hill in Ottawa May 1, 2012. Chris Wattie/Reuters

Share

Richmond Hill is a suburb north of Toronto, a place of nature-themed street names and cookie-cutter faux mansions. Relatively wealthy, multicultural and just far enough from Toronto’s lefty sensibilities, it is exactly the kind of place the governing Conservatives need to retain in order to stay in power following the next election in October. On a recent Friday morning, hundreds of Richmond Hill residents descended on the Bayview Hill Community Centre to hear Prime Minister Stephen Harper speak about his government’s new anti-terrorism legislation, and a world growing less safe by the day.

Hasidic Jews, Coptic Christians, turbaned Sikhs, toqued Leafs fans: Many, but not all, religions were represented in the crowd. Community centre staff were told in the weeks leading up to the event that it was going to be a fundraiser, but it felt more like a campaign rally, complete with cheering crowds, a flag-draped backdrop and a campaign-style slogan.

It was no accident that the minister plucked to introduce the Prime Minister on this day was Steven Blaney. As the minister of public safety and emergency preparedness, he helped to develop Bill C-51, otherwise known as the government’s Anti-terrorism Act 2015, which would give a host of new surveillance and seizure powers to Canada’s law enforcement and spy agencies. Blaney lauded Harper as “a man of principle and action, a man of conviction and vision, a man who uses every opportunity to stand up for what is good and right.” The room erupted as Harper took the podium.

Tall and lanky with a bald pate and thick eyebrows, Blaney cackled at jokes and smiled for selfies after Harper’s speech. When asked about privacy issues arising from the bill—and critics’ claims that giving the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the RCMP more powers is a demonstrable invasion of law-abiding Canadians—Blaney answered: “I would get back to what the Prime Minister has just said, that there is no liberty without security.”

When he finished his spiel, Blaney looked over at Harper, who was glad-handing nearby. “The Prime Minister is very popular, isn’t he?” Blaney gushed. “Look at all those people lining up to take a picture with him. The last time I saw something like this was when he was in my riding on Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day.” He gazed at Harper for what seemed like an uncomfortably long time.

Loyalty, deference and a disarming smile: These three qualities appear to have taken Steven Blaney from a failed political candidate in rural Quebec to the top of Public Safety Canada, which, according to Treasury Board figures, is responsible for roughly 65,000 employees and a $6.8-billion-overall yearly budget.

Along the way, he has defended some of the more rock-ribbed identity issues associated with the Conservative brand; a stranger reading his various partisan attacks would be forgiven for thinking that this former engineer had channelled American libertarian Ron Paul in Canadian Parliament. He is the country’s eternally reliable pro-prison, anti-census, support-the-troops, kill-the-gun-registry politician—Ottawa’s ultimate yes-man, critics say, in a town where such a thing is often generously rewarded. But, as Blaney’s star rises, so too does the worry that having the ultimate yes-man in charge of Canada’s security and surveillance means he is unable (or unwilling) to be anything but Stephen Harper’s ultimate echo chamber in one of the country’s biggest and most powerful ministries.

Born in Sherbrooke, Que., Blaney’s political life began in the town of Sainte-Marie, roughly 60 km southeast of Quebec City. Norm Vocino, a political operative working for the Conservative party, thought of Blaney in 2005. Vocino had the unenviable job of filling the Conservative electoral slate in a province that had proven resistant to Harper’s Western populist strain of conservatism. Blaney (who declined Maclean’s request for a follow-up interview) popped onto Vocino’s radar in part because he’d run unsuccessfully for the ADQ, a right-of-centre provincial party in Quebec, in 1998.

Blaney, who was then working as an engineering consultant, was nearly brought to tears at the honour of being asked to run for the Conservatives. “He was so incredibly excited. He actually collapsed and we had to bring him to another room,” says a Conservative operative. “We were a bit worried about his enthusiasm, but he’s aged well over the years.”

In 2010, Blaney was called upon to defend the government’s decision to cut the long-form census. Sent to roughly 20 per cent of Canadian households every census year, it was seen as a crucial demographics tool by statisticians, in part because it was obligatory. The Conservative government saw it as a massive intrusion into the lives of Canadians; critics also say the Conservatives were wary of the census because, in tracking disadvantaged groups, it tended to spur further demands for social services spending.

On July 21, 2010, Statistics Canada’s chief statistician, Munir Sheikh, resigned in protest of the government’s decision. The response French Canada got to the controversy from Blaney: “160,000 people refused to answer [the mandatory census], and those people were subject to a fine or prison. That’s a lot of people to put in prison, especially when you see all the riots going on,” Blaney said, in an apparent reference to the G20 riots in Toronto the month before. He repeated virtually the same words three months later in the House of Commons when the opposition attempted to revive the issue.

As a backbench MP, Blaney had little stake in the long-form census, and even less in Statistics Canada, which falls under the purview of Industry Canada. Yet, he was the fiercest defender of the government’s decision to get rid of it. Former Independent MP André Arthur thinks he knows why. “He’s probably a bit naive, very sincere and very obedient,” says Arthur, who represented a neighbouring riding of Blaney’s until 2011. “When the Prime Minister’s Office say, ‘Jump,’ he says, ‘How high?’ ” Nine months later, following the 2011 election, Blaney was appointed veteran affairs minister.

If Blaney’s key to moving up in Ottawa was slavish loyalty, his political survival in his riding of Lévis-Bellechasse was due to his personal touch. “I’ve rarely seen a politician who is so close to his electorate,” says insurance broker Mario Roy, who lives in Blaney’s riding. An athletic type, Blaney has participated in many charity runs and swims in Lévis-Bellechasse. His many funding announcements— $101,111 for a new soccer field in 2010 and $183,000 for two local snowmobile clubs in 2012, for example—are duly catalogued in the local press.

His devotion to his riding has kept him elected, even as Conservative fortunes in Quebec sank. In the months before the 2011 election, Harper’s Conservatives dangled the idea of funding a new hockey arena in Quebec City—stoking the hopes of thousands of Nordiques fans pining for a return of an NHL franchise to the city. In a now-infamous photo, Blaney and six other Conservative MPs decked themselves out in Nordiques jerseys and gave the camera a hearty thumbs-up, which became the stuff of cruel irony when the government ultimately balked at funding the arena. “It cost them dearly in Quebec,” says Roy. Six of 11 Conservatives lost their seats, yet Blaney won his riding by nearly 6,000 votes. In a 2013 cabinet shuffle, he was appointed minister of public safety and emergency preparedness—the only Conservative MP from Quebec to receive a promotion.

Getting elected in Quebec gets you a fair bit of clout in the Conservative party: Four of the five Quebec MPs made it into cabinet. Yet Blaney certainly hasn’t thrown his weight around. “You have ministers who think they’re bulletproof, and they freelance. He’s a minister from Quebec, so he could be bulletproof if he tried, but you just tell him what to do and he does it. He won’t freelance,” says Bruce Carson, a former senior Harper aide.

Because Bill C-51 must pass legal muster (and a likely court challenge), the Department of Justice, not Public Safety, was responsible for the bulk of the bill’s legislative underpinnings. Blaney’s job is twofold, says security analyst Wesley Wark: He must consider (and often resist) demands for more powers coming from his own department from the likes of the RCMP and CSIS. As well, he must be the bill’s chief champion and biggest defender.

On the former, Wark has misgivings about Blaney’s abilities—too little backbone, he suggests. On the latter, though, he thinks Blaney was born for the job. “Blaney stays on message, and he’s clearly not given to stepping out of the framework. That suits the government style,” Wark says.

In the frenzy of the announcement in Richmond Hill, Blaney might be forgiven a wee mistake. The “no liberty without security line” he attributed to Harper didn’t actually come from the Prime Minister’s lips, but from Blaney himself. He first uttered the line on Nov. 4, during a parliamentary debate about a bill that would expand CSIS’s powers. He used it again during a public safety committee meeting 20 days later, and again during a television interview on Jan. 4. “There is no liberty without security,” he said two days after the Richmond Hill event, during yet another television interview. It’s a catchy line.