Mulcair is everyone’s target. Here’s how he plans to win.

Thomas Mulcair forced the Liberals to move left. Now he’s chasing the Conservative vote. Paul Wells on the man to beat, with miles to go before he sleeps

mACLEANS-MULCAIR-08.27.15-ST. CATHARINES, ON: NDP leader Tom Mulcair makes a campaign stop in Brantford Ontario on August 27th, 2015.

Share

On Aug. 27 I caught up with Thomas Mulcair’s NDP campaign bus, for the second time in this odd election season, in what threatens to become our regular meeting spot: a desolate stretch of Eglinton Avenue in Toronto, where a former Saskatchewan finance minister, Andrew Thomson, is running for Parliament.

Thomson’s candidacy, like much of the paraphernalia of the Mulcair campaign, is an example of leaden means in pursuit of romantic ends. What the NDP is trying to do here is unprecedented. The way they are going about it is as unsexy as, well, Tom Mulcair.

No New Democrat has ever been elected to represent Eglinton–Lawrence. It used to be a Liberal bastion. An Anglican clergyman named Roland de Corneille held it for the party through most of the 1980s, fending off the Mulroney onslaught of 1984. Finally Joe Volpe took the nomination from de Corneille in 1988, through the riding’s traditional means of succession: internecine organizational battles among Liberals. Volpe then represented the riding for, if we’re being honest, altogether too long before the Conservatives’ Joe Oliver managed to end the Liberal era on his second try in the 2011 election. Oliver went on to become Stephen Harper’s second finance minister.

To win Eglinton–Lawrence, Andrew Thomson, who does not live in the riding and who has only recently returned to Canada from overseas, will have to leapfrog past both the incumbent and the entrenched Liberals. The previous NDP candidate here won less than 12 per cent of the vote in 2011. Thomson’s got his work cut out for him.

Related: An interview with Andrew Thomson

He’ll have help. “We’ll be here every week,” a Mulcair staffer said to me as I wandered into Thomson’s storefront campaign headquarters.

There, indeed, was Mulcair, a former Quebec environment minister next to the former Saskatchewan finance minister, and already you could see some of the method in this madness. Two seasoned political pros, standing side by side to complement each other’s credibility.

“I can tell you in this riding, there are two choices to defeat Joe Oliver,” Thomson said, acknowledging the Liberal, lawyer Marco Mendicino, who defeated the confusing ex-Conservative Eve Adams for that party’s nomination here. “But there is only one option if you want to defeat Stephen Harper and put a new government in place in Ottawa. And that is to vote NDP . . . ” The rest of his remarks were drowned out by applause from local supporters.

And you know what? Maybe they will. Vote NDP, I mean. Not just here in the concrete expanses of Eglinton–Lawrence but across Ontario, the campaign’s most important battleground province, and beyond. If the big crowds and the early polls are any indication, 2015 could be an even bigger election for the NDP than the breakthrough of 2011.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

Later that day, in a brief interview before an evening rally in Brantford, Mulcair would list some of the high points: the day the crowd reached the fire-code capacity at the Refined Fool Brewing Co. in Sarnia, or the throng that turned out in a park in Perth. At the latter event, Mulcair said, “Some of the old-timers who’d been around, working in the party for 40 or 50 years, told me, ‘Listen. Tommy Douglas came here. Ed Broadbent came here. We had big meetings: Sixteen, eighteen people!’ ” This time, he said, “We had 450 people on a hot Friday afternoon. And people were excited. They sensed that something is happening.”

As I cut that interview short so he could get back to campaigning, Mulcair added: “And I’m excited. You can add that.” Well, good. I’m glad we cleared that up. Because the evidence of excitement from his campaign-trail body language and discourse is intermittent.

“Toronto is the most important city in Canada,” he told the crowd at Andrew Thomson’s campaign HQ. “It’s home to 80,000 new immigrants who come to Toronto every year to pursue their dreams. The GTA is home to over three million highly educated and skilled workers who make up nearly one-sixth of Canada’s entire workforce and boasts 40 per cent of corporate headquarters in Canada.” He sounded like Siri, reading a Wikipedia entry on Toronto aloud for an iPhone user on handsfree. “Produces over 15 per cent of Canada’s GDP.”

Related: Read an excerpt of Thomas Mulcair’s book, Strength of Conviction

There is a school of thought, among people who watched this campaign closely even through the August doldrums, which believes Mulcair has been slouchy and low-energy for a front-runner. Partly this is who he is, and since you and I can be slouchy and low-energy too at times, it is hard to begrudge him his moments. But there is also some calculation in it. Each new voter the NDP is chasing this year is his or her own private Eglinton–Lawrence, somebody who has not voted NDP recently and may never have. Mulcair is hunting the fabled “blue-orange switcher,” that rare, but not unheard-of creature who doesn’t want to vote Liberal but who hesitates between Conservatives and New Democrats as champions of ordinary folks.

You don’t hunt those votes with flash and dazzle. In fact, a boisterous outsider will scare blue-orange switchers away. You need to reassure them. Lull them. Remind them of the leaders Ontario voters have supported in the past: Bill Davis, Mike Harris, Jean Chrétien, Stephen Harper. Plodders you could trust with the keys, whatever their policy stance.

“Change is only appetizing when you have an alternative you can turn to,” a senior Mulcair adviser told me before this campaign began. This may sound like a stretch, but Mulcair’s position is like Barack Obama’s in the 2008 and 2012 United States presidential elections. Like Obama then, if Mulcair now says something to excite his dedicated voter base, he could scare off the next skittish rookie NDP voter on whom victory depends.

Related: Marshall Ganz, who worked on Obama ’08, on ‘snowflake’ organizing

This is one reason why Mulcair is so intent on running as an advocate of balanced budgets. By coincidence, I followed him on a day when the Liberal leader, Justin Trudeau, delivered one of this race’s big surprises: that a Liberal government would run $10-billion deficits for its first two years in office, then something smaller in its third year, before eliminating the deficit in his fourth, should Trudeau even be lucky enough to see four years as prime minister.

It’s a flanking move. Even as Mulcair shores up his managerial credibility by practically stapling himself to Andrew Thomson, Trudeau calls for big infrastructure spending, and to heck with balanced budgets. Mulcair is chasing Harper’s supporters. Trudeau is after Mulcair’s, a fox in the lefty henhouse.

Related: An economist explains what he thinks about when considering infrastructure spending

Mulcair is learning that higher hopes bring bigger obstacles. The NDP leader has become his opponents’ target much earlier than Layton ever did. Partly because there is more of the old-time backroom pol and less of the leprechaun in Mulcair than in Layton, his opponents were quick to get over any reticence in their attacks. Day after day, Trudeau has been deriding Mulcair as a man who would let the needy twist in the wind. Harper has ordered up a suite of ads that decry Mulcair’s supposed addiction to “reckless spending.” Having sought the policy middle and the centre of attention, he has arrived only to find himself surrounded.

Taking questions from reporters at Thomson’s headquarters, Mulcair was asked about Trudeau’s plan. For once some anger flashed. “I’m tired of watching governments put that debt on the backs of future generations,” he said. “Stephen Harper’s approach has always been, ‘live for today, let tomorrow take care of itself.’ Well, at some point, you have to start having different priorities.” The Liberals don’t, he said.

How could Mulcair balance the books while spending more in some areas? By spending less elsewhere, he said. Harper “subsidized oil companies to the tune of billions of dollars. We won’t do that. He spent a billion dollars fighting First Nations,” in court cases over resource projects. “We won’t do that. He’s spent a billion dollars on the Senate. We would try and make sure that Canadians never spend another penny on that.” Big applause for that last line. Shuttering the Senate would require the unanimous consent of all provincial legislatures, so it might be some time before Mulcair could get that job done. Maybe never. Never, for my money, is a good bet. But the sentiment was popular with this room.

https://macleans.ca/economy/economicanalysis/why-the-ndps-exact-plan-for-the-federal-corporate-tax-rate-matters/

Ontario matters in this race because it’s home to 121 ridings, one more than Quebec and British Columbia combined. But also because all three of the traditional big parties are competitive here, so there are close fights in dozens of ridings. It was three-way splits that accounted for much of the Conservatives’ success in 2011. They won many of their 73 Ontario seats because New Democrats and Liberals divided the larger anti-Conservative vote. To win again the Conservatives must hold many of those seats. To end the Harper era, Liberals and New Democrats must take them. Other campaigns have been won in the air as leaders bounced from province to province seeking advantage. This one will be fought to a great extent on buses, in the 905 area code around Toronto and in southern Ontario.

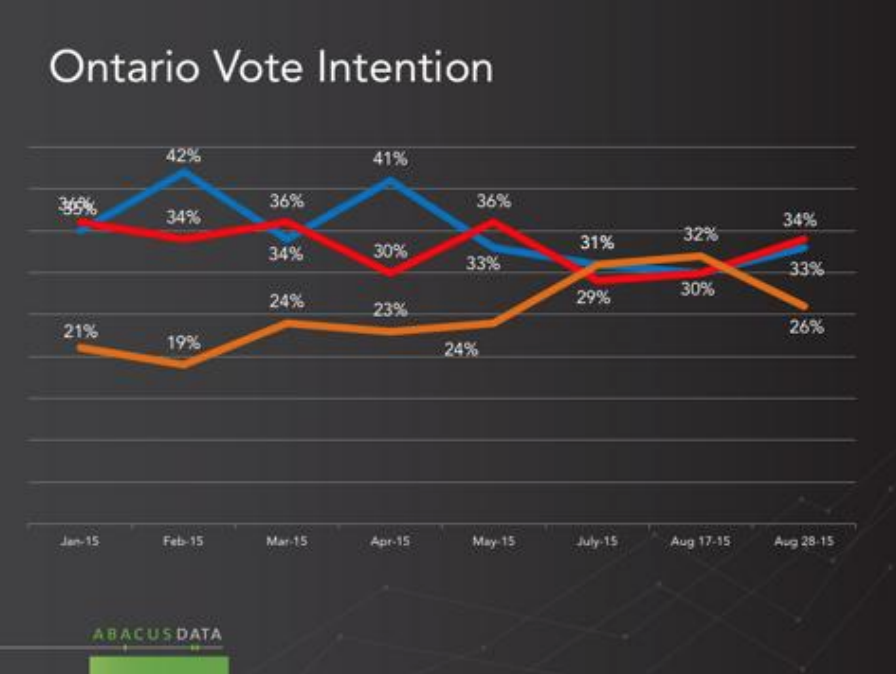

The NDP remains in the lead nationwide, but it has seen a dip in support in the past two weeks that must unnerve its supporters, especially in Ontario, according to a new Abacus Data poll released this week. The NDP’s national level of support is down four points to 31 per cent, edging out the Conservatives at 30 per cent and the Liberals at 29 per cent. In Ontario, the NDP has lost six points to 26 per cent, putting them in third place behind the Conservatives at 33 per cent and the Liberals at 34 per cent.

But the NDP has formidable strengths. In the year and a half since January 2014, the proportion of the population who would consider voting NDP, regardless of whom they support right now, has grown six points to 62 per cent, Abacus found. This potential vote has shrunk for the Liberals during the same period, from 60 per cent to 55 per cent, and for the Conservatives, from 45 per cent to 42 per cent. This suggests the Conservatives, in particular, have very little room to grow beyond their current support.

And the more Canadians get to know Mulcair, the more they seem to like him. In exclusive polling for Maclean’s, Abacus found that Mulcair has overtaken Harper on a range of questions designed to test respondents’ attitudes toward leaders. In January a plurality of voters thought Harper, of the three big party leaders, would be best to negotiate a contract on their behalf; advise respondents on how to invest their money; and have good ideas for children about their future. Mulcair has gained on Harper on all those questions, overtaking him as a hypothetical contract negotiator and child career counsellor. (By a wide margin, respondents still believe Trudeau would be best if they needed a political leader to cook a meal or pick a movie to watch.)

[rdm-gallery id=’533′]

With the stakes so high, the players sometimes call in reinforcements. Mulcair’s is Thomson, the former Saskatchewan budget-maker who helps compensate for the incumbent NDP caucus’s limited supply of cabinet timber. When he faced the same problem in 2006, Harper campaigned with Bill Davis, the legendary former Ontario premier. When he needed a Toronto breakthrough in 2011, Harper campaigned with Rob Ford, who was then the city’s not-yet-humiliated mayor.

Trudeau has recruited Kathleen Wynne, the Ontario premier who surprised a lot of people by winning re-election last year. She managed the feat despite the weight of scandal over two gas plants her predecessor Dalton McGuinty cancelled to improve his own electoral chances, at horrendous cost to the taxpayer. And she did it even though several members of the Harper cabinet decried her plan to add a compulsory-contribution provincial pension to supplement the Canada Pension Plan.

Plainly neither Harper nor Wynne view her re-election as having settled the matter. She has already appeared twice with Trudeau and will do so again. Her chief campaign strategist, David Herle, is working for Trudeau this summer. In an interview with Maclean’s she was extraordinarily blunt about wanting to see Harper defeated, and by Trudeau, not Mulcair.

Recent polls suggest more Ontarians disapprove of Wynne’s government than approve, and it was fashionable to predict her support would backfire against Trudeau. Trudeau’s early, tentative success belies that prediction. Wynne’s many detractors were unlikely to take Trudeau seriously under any circumstance, and of her outnumbered admirers, he needed only a fraction to improve his own standing markedly. That’s what seems to have happened.

In recent days all three party leaders have been buzzing around Ontario, and the Green party’s Elizabeth May was preparing to leave her British Columbia redoubt to join the Ontario fray. Mulcair was born in Ottawa but has made his career in Quebec. Through long experience, beginning when he ran to succeed Jack Layton after his predecessor’s shocking death four years ago, he has become familiar with Ontario, a province many Quebecers know only vaguely and, as neighbours often do, through a haze of preconceptions.

“This is my sixth visit, here, in this town,” he said in Brantford before his evening rally. “So I’ve had a chance to get to know people. You get a sense of place.”

He talked about his early days as the young director of Quebec’s Office des Professions, taking on the province’s college of physicians and surgeons over the sexual abuse of patients by doctors. He talked about his decision to walk away from Jean Charest’s cabinet rather than let condominiums be built in a provincial park. “So that’s my background too. That’s who I am. That’s the inner drive I have that—I guess values is sometimes a word that’s overused, but really, that’s what it is.” He was self-conscious. This business of self-promotion can make anyone look silly. It made him tentative, searching for his words. “It’s the fire in the belly to stand up and do the right thing.”

It is churlish to deny any political leader the belief that they are doing the right thing. They all do, and the challenge each faces is that they are under fire from the rest, and that this dispute is being litigated with particular intensity in the cafés and community halls of the country’s biggest province. Six more weeks of this lie ahead. Whoever wins, if any of them even captures enough seats to make a credible claim of victory, will have fought hard to earn it.