What rules apply to Mark Carney’s political activities?

John Geddes investigates exactly what a bank governor is and is not allowed to do

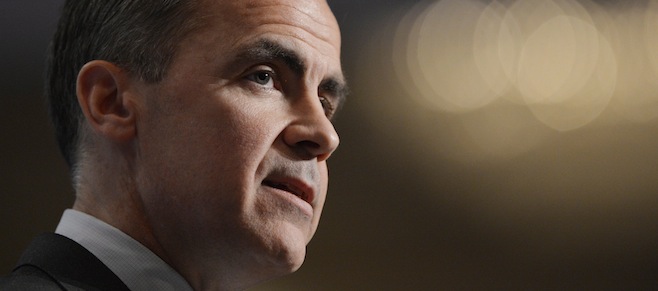

Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney walks to his seat at a news conference in Ottawa, Monday Nov. 26, 2012 after it was announced that he will be the new head of bank of England. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Fred Chartrand

Share

In the swirl of debate around Mark Carney’s reported involvement with Liberals eager to have him run for their party’s leadership, there’s been a troubling lack of precision about exactly what rules apply. Some commentators hold that since Carney is governor of the Bank of Canada he must avoid any hint of contact with partisan politics. Others shrug off the fruitless courtship as standard Ottawa stuff and no big deal.

For my part, I’m less interested in the gut reactions of observers than in finding out exactly what Carney is and is not allowed to do. If you imagine that would be a straightforward inquiry, you’d be wrong. The Bank of Canada’s lawyer, I’m told this morning, holds that Carney is restrained, when it comes to party politics, with respect to any “specific activity undertaken in the public domain,” like political fundraising or actually running for office.

If that standard applies, Carney has done nothing wrong. The widely discussed Globe and Mail story that set off all the debate is interesting precisely because it reports on what happened entirely in Carney’s private domain, if you will, when Liberals tried persuading him to contest the party’s leadership. The Globe says he was receptive, though of course it all went nowhere, and he ended up surprising everyone last month by announcing he’ll be stepping down as head of Canada’s central bank next June to take over England’s.

When it comes to sorting out what Carney is not supposed to do in terms of political activities, the most important guidelines to consider are those published last year by the Privy Council Office, the nerve-centre of the federal public service, and a logical source of ethics direction for top federal appointees. The document Accountable Government: A Guide for Ministers and Ministers of State contains an annex called “Ethical and Political Activity Guidelines for Public Office Holders.”

Stringent limitations are imposed on top public servants. The guidelines note that the Public Service Employment Act, which doesn’t apply to Carney, sets this tight restriction on departmental deputy ministers and others at that high level: “A deputy head shall not engage in any political activities other than voting in an election.” It goes on to broaden that rule’s application: “These guidelines impose a similar prohibition on all deputy heads, deputy ministers, associate deputy ministers, associate deputy heads and persons of equivalent rank, including the deputy heads and chief executive officers of Crown corporations…”

In an email reply to me this morning, the Bank of Canada confirms Carney is bound by these guidelines. (There is, however, nuance here. The bank says he is subject to the guidelines, not as governor, but in his lesser role as Canada’s alternative governor to the International Monetary Fund. That’s because as governor, he’s appointed by the bank’s board of directors, which gives him special status, whereas his IMF appointment is made directly by the federal cabinet, and thus makes him subject to the Privy Council guidelines.)

Despite the fact he’s covered by those guidelines, and they seem to ban any political activity at all beyond voting, the bank’s email to me this morning suggests the bank sees its own Conflict of Interest guidelines as key here. These guidelines are much more flexible, allowing for “an appropriate balance” between political activity and the bank’s need to remain impartial.

“Defining partisan or political activity for the purposes of the bank Conflict of Interest guidelines,” the email from the bank’s media spokesman said, “is an exercise of judgment of the bank’s General Counsel. In the context of any restraint on one’s right to be politically engaged, it must relate to a specific activity undertaken in the public domain (i.e., fundraising, running for office, etc) and which therefore has an implication for and connection with the interests of the bank.”

That underlining, which is there in the email, suggests the bank is emphasizing the fact Carney didn’t do anything in public that suggested in any way a partisan leaning. The question, it seems to me, is whether that is really the standard that matters, or whether a tougher one—no political activity but voting—also applies.

(UPDATE: I note up above in parenthesis, so non-wonks can skip over it, that Carney is covered by the Privy Council guidelines because of his IMF appointment, though not because of his main Bank of Canada role. The same odd application of the ethics rules holds in his case with respect to the federal Conflict of Interest Act; he’s subject to it as Canada’s alternate governor to the IMF, but not as governor of the Bank of Canada. Still, he’s one man, so the act applies, as the bank’s spokesperson has confirmed by email today.)