Why the NDP’s past is never dead

Paul Wells on the NDP’s fine balance of principles and political power

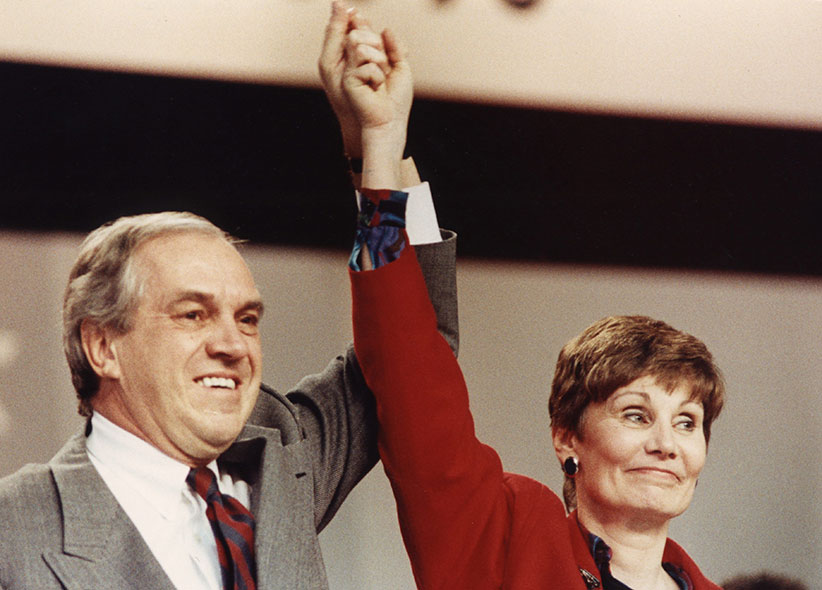

Ed Broadbent raises the arm of Audrey McLaughlin at the New Democratic Leadership Convention, December 1989. (CP)

Share

Our text today is from William Faulkner: The past is never dead. It’s not even past. The news from Edmonton is that the New Democratic Party struggled through the weekend to assay the competing claims of principle and power. But good luck finding any moment in the NDP’s history when principle and power didn’t define the party’s main axis of division and self-doubt.

In Edmonton, power was represented by the only woman in Canada who holds both an NDP card and a seat at the head of a cabinet table, Alberta Premier Rachel Notley. (Greg Selinger in Manitoba has both of those too, but it will be a surprise if he keeps the good seat past next week’s election.) She asked her party to stand for the rights of workers—including those who produce fossil fuels, a notoriously legal and often valuable commodity—to keep working. More broadly, she said what leaders of ideological parties always say after winning elections: that the good you can do from the sidelines is no match for the good you can do from the big chair.

Principle, or at least a kind of yearning, was championed by the authors of the Leap Manifesto, which decries “new infrastructure projects that lock us into increased extraction decades into the future.” The delegates listened to both sets of visitors and decided they want to hear more from the manifesto writers. Notley was not pleased.

At some point amid the shouting, word spread that a man was down, a Mr. Thomas Mulcair of Outremont, in Quebec. It was not entirely clear what he was even doing in Edmonton. Some witnesses claimed that earlier he had delivered remarks to the convention, but on the central point of debate—should New Democrats win elections, or should they say things that are true and beautiful, if only to one another?— his answers were not held to be useful. If you are for power, you should bring your movement closer to power. If you are for principle, you should say something memorable at least once. The crowd helped Mulcair to his feet, waited until the dazed man’s senses had returned, then parted awkwardly to catch flights for home.

It was all so familiar. In 1989 the NDP found itself without its leader of 14 years, Ed Broadbent. Dave Barrett, a former premier of British Columbia, ran to replace him as the candidate of power, more or less. Audrey McLaughlin ran in seeming defiance of any notion of power. She had been an MP for all of two years (twice as long, it must be said, as Barrett). She represented Yukon, a riding where coattails freeze: If she carried every seat in her home territory, the total number of seats she would carry would be one. All of this sounded wonderful to New Democrats. They made McLaughlin their leader. At the next election they won nine seats, including every seat in Yukon.

Before Barrett and McLaughlin there was the Manifesto For an Independent Socialist Canada. This was in 1969 and the movement behind the manifesto was called “the Waffle,” because the strangest things seemed funny in 1969. “The development of socialist consciousness” must be the NDP’s “first priority,” the Waffle manifesto said. By 1972 a young New Democrat named Stephen Lewis had been Ontario’s provincial NDP leader for two years and was hoping to win an election. The Waffle people wouldn’t stop nattering at him. He called them “an encumbrance around my neck.” He finally ran the Waffle out of his party.

These days Stephen Lewis is older and his family is at the centre of the Leap Manifesto. There is no real contradiction here. Pragmatism and principle, discipline and catharsis, contend in each of our hearts. That a man could be vexed by manifestos in his youth, only to help write them in his dotage, shows only that hope needn’t wane as years pass.

Tom Mulcair, I learn, led the NDP into the 2015 federal election. At one point he ran Internet ads bragging about the party’s “offer” to Canadians. What a peculiar word. Conspicuously mercantile: Here is the stock of goods and policies we will give you in return for your vote. Back your truck up to the loading dock. Hope dies in politics when leaders start talking about their offer. Somewhere in the middle of the mess, politics must contain a call, something that sounds like a yearning for a better world. What New Democrats said in Edmonton is that they will make compromises, absolutely, you bet. But not in return for nothing. The weekend’s events amounted to an announcement that this party cannot give principles and power equal weight because it has known forever that it can live without one, and it is pretty sure it can’t live without both.