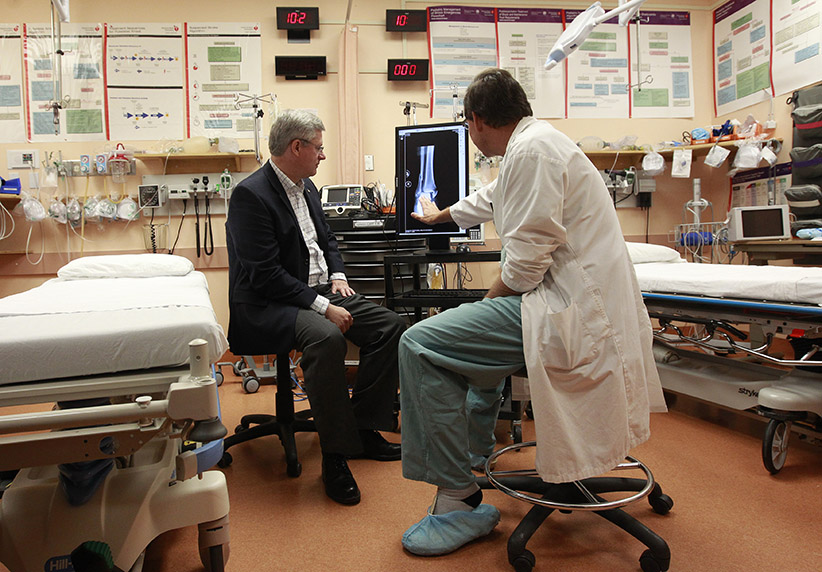

Missing on the campaign trail: Talk of health care

Pharmacare, a seniors strategy, home care: All relegated to passing references. Evan Solomon on the missing heart of the election campaign

Professor Jan Pirk (L), doctor Marian Urban (C) and suture nurse Diana Vapenkova perform a heart surgery at the Institute of Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IKEM) in Prague, June 28, 2012. A Czech medical team led by Pirk has performed a breakthrough operation on a 37-year-old heart failure patient, replacing his heart with two mechanical blood pumps, HeartMate II. The man is the first to survive such surgery, which was performed on April 3. The exact operation was previously conducted by heart surgeons in Texas, United States. However, the patient died one week later. Picture taken on June 28, 2012. REUTERS/Petr Josek (CZECH REPUBLIC – Tags: HEALTH SCIENCE TECHNOLOGY SOCIETY)

Share

Put out an alert. Send out a search party. Print a face on the side of a milk carton. Something has to happen to locate the missing campaign debate about health care. It has simply vanished.

In its place, pails of pixels are being filled trying to find out why Nigel Wright cut that $90,000 cheque to Mike Duffy. There is endless talk about a recession redux. Child care, pipelines and security issues are all eliciting Kardashian levels of political scrutiny. That’s not a bad thing. But health care has gone as silent as a Chaplin film.

“It’s a major missed opportunity for the opposition parties,” Kevin Page told me. The former parliamentary budget officer knows how fundamental this matter is to all levels of government. “Rarely do you have this much public support around an issue, and yet you don’t see it prominently displayed in any party platform,” Page says.

He’s right about public support. A recent Abacus poll found 56 per cent of voters aged 45 and over said health care is their top concern. Even 43 per cent of Millennials—those aged 18 to 29—put health care as their No. 1 issue. That’s higher than job creation, taxes, middle-class incomes and the environment. Abacus found issues such as crime and security poll no higher than 11 per cent for all ages. So why the political silence?

The answer goes back to the Lunch of 2011. In December of that year, the finance minister, Jim Flaherty, hosted his provincial and territorial counterparts in Victoria at what was supposed to be a friendly lunch. It wasn’t. Flaherty shocked the smoke out of their salmon by suddenly handing them a controversial new health care funding formula. No negotiations. No questions. A deal chipped in stone brought down from Harper’s mountaintop in Langevin Block.

The federal government promised to continue the so-called escalator—a six per cent increase in funding each year—for five years, until 2016-17. Then, reality hits. The government will tie its health care contribution to the provinces to economic growth, with a floor of three per cent. So, here we are, four years later, and, in case you haven’t noticed, economic growth is pretty hard to come by. In other words, get ready to hit the floor. Hard.

Health care spending by the provinces is almost certain to outstrip GDP growth, and the aging demographic will make it worse. “Premiers feel strapped, regarding fiscal sustainability,” Page says. For the provinces, which spend about 40 per cent of their budgets on health care, it will soon seem like a patient learning to function without a limb. This explains why Quebec Premier Philippe Couillard, a surgeon who knows an amputation when he sees one, is raising the matter of the Canadian Health Transfer payments.

Elections are as much about controlling what is not being debated as they are about what is being debated. That’s why Stephen Harper has not sent out a Franklin-style search party looking for the lost health care debate. He wants this election to be about the economy and security, not health care, which he knows plays well for the opposition. It’s not just strategy. Harper fundamentally believes health care is a provincial jurisdiction and that Ottawa should back off.

That’s not the way it’s worked historically. In the 1960s, Ottawa contributed 50 per cent of the health spend. By the end of the decade, it could drop below 20 per cent. “The federal government is dangerously close to being non-players in health care in Canada,” Dr. Chris Simpson, the president of the Canadian Medical Association, told me.

Simpson is desperate to make seniors’ care an election issue, but, so far, he’s like the kid who buys new shoes for the prom, but never gets an invitation. He believes the system is at the breaking point, but the federal government is ignoring obvious solutions. For example, why aren’t long-term-care facilities eligible to apply to the Building Canada Fund? Aren’t they basic infrastructure? “Why no one else has taken this up in this campaign is baffling,” he laments.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

The NDP and Liberals insist health care is an important issue for them, and both have hinted that they might announce something soon. It’s hard to take seriously. After all their other promises, there’s just not a lot of money left for them to allocate. Is this a major political blunder, or do they know that people just don’t vote on this issue?

“Parties can talk about improving health care, but can’t deliver real results,” says pollster David Coletto, CEO of Abacus Data. It always gets bogged down in debates about jurisdiction and money. So, while it’s a top voter concern, he believes the public views it like protesting snow in winter. No one believes there’s anything he or she can do about it.

Still, even federal election campaigns can’t avoid reality forever. The fundamentals of the Canada Health Act are in jeopardy. Notions of universality and accessibility are becoming quaint concepts, like hand-delivered mail. Pharmacare, a seniors strategy, home care: This stuff used to be explosive political material. Today, they are passing references on a party website.

Most Canadians say they need an emergency health care cure. So far, though, the campaign is just like a visit to an overcrowded hospital: Expect a long wait.

On the web: Have a comment to share? Follow Evan Solomon on Twitter @EvanLSolomon