Pickton inquiry report met with anger, recrimination and tears

After two years, dozens of witnesses, 1,500 pages and $10M, report does little to satisfy families of Pickton’s victims

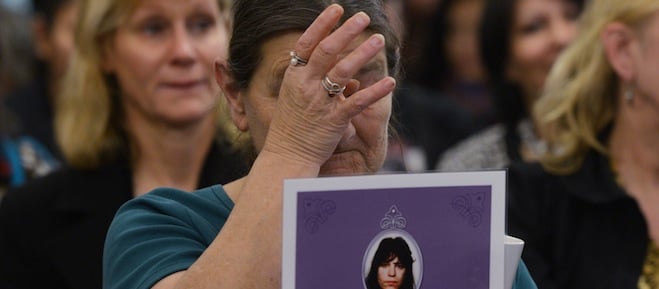

A woman reacts as Commissioner Wally Oppal delivers the final report of the Missing Women Inquiry in Vancouver, Monday, Dec.17, 2012. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward

Share

It is one of life’s enduring mysteries that about six Vancouver city blocks down Hastings Street from the rich wood panelling, gleaming granite and fine carpets of the Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue, women are climbing into cars with strangers to sell their bodies for a $10-rock of crack cocaine. That they vanish into streets and alleys, into single-room occupancy hotels, into emergency shelters. That even today, with the infamous predator Robert Pickton in jail this past decade, women still sometimes vanish into the ether—their photographs posted on shelter bulletin boards and flapping from telephone poles in the city’s notorious Downtown East Side.

It is one of life’s enduring mysteries that about six Vancouver city blocks down Hastings Street from the rich wood panelling, gleaming granite and fine carpets of the Morris J. Wosk Centre for Dialogue, women are climbing into cars with strangers to sell their bodies for a $10-rock of crack cocaine. That they vanish into streets and alleys, into single-room occupancy hotels, into emergency shelters. That even today, with the infamous predator Robert Pickton in jail this past decade, women still sometimes vanish into the ether—their photographs posted on shelter bulletin boards and flapping from telephone poles in the city’s notorious Downtown East Side.

They are lost to the families, in many cases, lost to society. They are the “Forsaken” as retired B.C. Appeal court justice Wally Oppal titled his five-volume report of the Missing Women Commission of Inquiry, released Monday during a chaotic, tear-filled event at the Wosk Centre.

Outside the centre, First Nations people sang and drummed and held dozens of sheets of paper, each with a name and a picture of a women missing or dead. There was Sherry Irving, and Samantha Belcourt and a woman named Mary Ann Clark, who lacked even a photo to accompany her name, as though she passed invisible through this life.

Inside the centre, Oppal stood before a news conference packed with journalists, family members and advocacy groups, ready to share the results of an inquiry that seemed doomed from its inception in September 2010.

It was born in controversy and cynicism to investigate the utter failure for years of the Vancouver Police Department and the RCMP to recognize that the women vanishing from the neighbourhood were being slaughtered by Pickton, a simple-minded pig farmer from Port Coquitlam, B.C.

After two years, 93 hearing days, dozens of witnesses, 1,500 pages and $10- million dollars, the report seems to have done little to satisfy the aggrieved families of Pickton’s victims: the six he is convicted of murdering, the 27 others whose DNA evidence was found on his farm, and of the dozens more who fell victim to unknown predators.

It took exactly eight words from Oppal’s prepared statement— “The story of the missing and murdered women” — before the first attacks came from families and their advocates. “It’s not a story,” someone shouted. “It’s reality,” shouted another. “The Bible is a story,” added another heckler.

Oppal, stone-faced, pressed on, wearing his heart on his sleeve, calling the murders “a tragedy of epic proportions,” telling audience members this was “an emotional day, a challenging day for each family member.” He credited the dedication of family members “who continue to demand justice for their loved one” for causing this inquiry to be called. “I believe everyone connected with this inquiry has the same goal, to make the changes necessary to help keep our most vulnerable citizens safe and to stop the violence, to stop the violence against all women …”

“Hogwash,” shouted a heckler. And on it went for more than an hour, Oppal doing his best to lay out the report’s key findings to a crowd that had little interest in listening.

He spoke of the ineffective police co-ordination between Vancouver and the RCMP. He described the “systemic bias” that caused the police to dismiss as runaways the women, most of them drug addicted sex-trade workers, many of them aboriginal, even as the numbers piled into the dozens. He condemned the failure of Coquitlam RCMP to press an investigation and a Crown prosecutor to proceed with charges against Pickton in 1997 after he almost killed a drug-addled prostitute the inquiry called “Miss Anderson.” Had Pickton been charged then, rather than five years later many lives would have been saved, Oppal said.

“Why did it take so long for action?” Oppal asked.

From the back of the room came the sound of drums. Audience members rose, then singing and chanting filled the room. It was more than four minutes before it petered out and Oppal could continue. Some family members and dissident native groups who’d loudly proclaimed their voices weren’t heard during the inquiry showed little inclination to listen today.

Oppal pressed on through hisses and boos and sarcastic asides. There were muttered claims of racism. Some family of the murdered women tried to quiet the crowd, but with little success. The anger was deep, the cynicism engrained after years of police and government indifference. Others seemed mired in a learned helplessness. “You know what they don’t have for us is Kleenex,” a woman in the audience muttered in disgust, as though the thought of providing her own was beyond the pale. Those who boycotted the hearings because of a government refusal to offer legal representation claimed they were shut out of the hearings. Yet they seemed more than capable Monday of making their feelings known without a lawyer at their side.

There were more than 60 recommendations. Among them:

- a provincial compensation fund for the children of missing and murdered women;

- a healing fund for families;

- “equality audits” to ensure the police and Crown lawyers deal fairly with marginalized women;

- better training for those in police and justice positions to learn “the history and current status of Aboriginal peoples in the provinces;”

- better programs to prevent violence against missing women, and to enhance services in the Downtown Eastside.

The overarching recommendation was for a regional police force to replace the hodgepodge of municipal police and RCMP detachments in the Lower Mainland. As Oppal rightly noted, it is a common denominator of failed serial killer investigations, from Pickton to Clifford Olson to Paul Bernardo, that key evidence often falls between the jurisdictional cracks.

Ironically, Oppal had recommended a regional police force during a previous police inquiry he headed in 1994 — to no avail. Nor was there action to regionalize policing when Oppal served as attorney general in Gordon Campbell’s provincial Liberal government. And the odds of a move to regional policing now? Unlikely. The province has just signed a 20-year municipal policing contract with the RCMP.

Perhaps good things may yet come from the inquiry. But as Oppal’s presentation Monday ended in anger, recrimination and tears, there didn’t seem much to celebrate. And down Hastings Street, and in the alleys, it was business as usual.