The curse of Keystone XL

How U.S. mid-term elections could decide Canada’s energy future

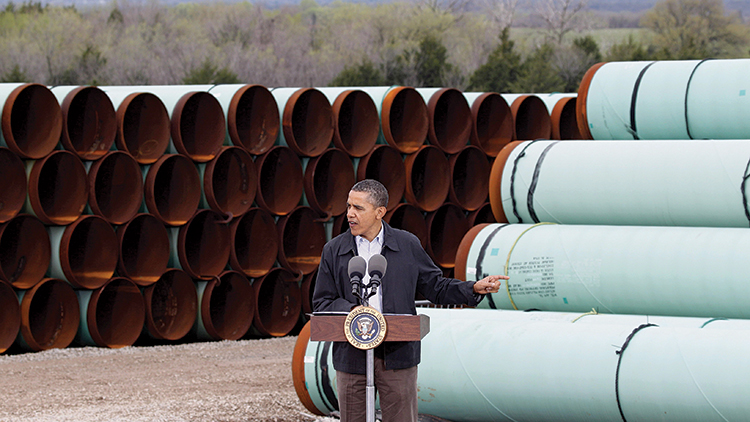

LM Otero/AP

Share

Just as the Obama administration’s review of the Keystone XL pipeline appeared to be moving toward a decision after a favourable final environmental report, a judge in the state of Nebraska last week threw the timeline for a decision into disarray—and potentially thrust TransCanada’s proposed cross-border pipeline into the approaching mid-term elections. A decision to approve, deny, or once again delay the pipeline could play a role in a handful of conservative states where pro-pipeline Democrats are struggling to keep to their seats in November’s elections. Those few tight races could determine whether or not Democrats hold on to their slim majority in the U.S. Senate.

While President Barack Obama himself is not on the ballot this November, the stakes are still very high for the White House. With control of both houses of Congress, Republicans would be in a position to thwart—and even roll back—the President’s legislative agenda. Republicans already have the House of Representatives and need only a net gain of six seats for a majority in the Senate.

The State Department had been in the process of a 90-day comment period on the environmental report, which was supposed to last until the spring. After that, Secretary of State John Kerry would have been free to make a recommendation to Obama on whether the pipeline was in the U.S. national interest. The Harper government has been pressing hard for a quick decision, but now that the Nebraska court ruled that the pipeline route through the state is “null and void” under the state constitution, the timeline for a permit decision has been thrown open.

Nebraska’s governor has appealed the ruling, which said that an independent commission, not the governor, should have reviewed the pipeline route. If an appeals court agrees, TransCanada would have to seek fresh approval in Nebraska—a process that could take months. Meanwhile, Obama’s State Department has said it is continuing on with its review while monitoring the litigation in Nebraska and consulting lawyers about how it should proceed. The timeline is “an open question,” an official said.

Pipeline opponents are calling on the Obama administration to pause until the Nebraska route is settled. “Under the court’s ruling, TransCanada has no approved route in Nebraska,” says Dave Domina, the lawyer for the landowners, who brought the suit. “The pipeline project is at a standstill in this state.”

Nebraska has caused the Obama administration to delay before: a decision to move the location of the route within the state in 2011 gave Obama a fortuitous opening to push the decision past the presidential election of 2012.

So which way does the November election cut for the Keystone XL pipeline? Polls suggest the project is supported by a large majority of Americans. But environmental groups say they have pledges from more than 70,000 people who plan to protest and engage in civil disobedience if the project is permitted. These are the liberal voters that Democrats are focused on mobilizing to vote in the mid-term elections. To have the Democratic base angry over a pipeline approval could be a major stumbling block going into November. Moreover, activist billionaire Tom Steyer has announced plans to spend $100 million supporting candidates who are pro-climate policy and anti-Keystone XL.

But the political calculus is yet more nuanced than that. The crucial battle for the Senate is playing out in a handful of toss-up races in conservative states—where vulnerable incumbent Democrats are running for re-election and Obama is unpopular. Their fate will likely determine the fate of the Senate. The most at-risk seats happen to include pro-pipeline incumbent Democrats in conservative states like Louisiana, Arkansas, North Carolina, Alaska and Montana.

There are two views of what this means for the pipeline. It is not a central issue in the races: Republicans are focusing their attacks on the President’s health care reform. But it will nevertheless play a role as a stand-in for a general approach to the economy, energy, environment‚ and a candidates’ alliance to the President.

One theory is that Obama has an incentive to approve the pipeline before the election in order to help those pro-pipeline Democrats. “In the final analysis [the pipeline] will get done not because of Republicans in the House ranting, but because of moderate Democrats in the Senate,” predicts Gordon Giffin, a former U.S. ambassador to Canada in the Clinton administration, whose Washington law firm counts TransCanada among its clients.

A pipeline approval would help these moderate Democratic candidates get re-elected by showing voters that their voices have an impact in Obama’s Washington, says Giffin. “The moderate Democrats want to say to voters, ‘Send me to Washington because I can affect the thinking in the Senate and the White House’—and the White House has to demonstrate that their voices are respected,” says Giffin.

This may be the case in particular for one imperilled Democratic senator, Mary Landrieu of Louisiana—a pro-pipeline state that is home to Gulf Coast oil refineries. Landrieu, a fervent supporter of Keystone XL, happens to chair the Senate energy and natural resources committee. Her senior role in Congress is part of her pitch to voters in what polls show to be a tight race against her Republican rivals. An approval for the pipeline could help her show she has influence in Washington. “I think if she had her druthers they would approve it and she can demonstrate that she helped make it happen,” says Bob Mann, a mass communications professor at Louisiana State University with extensive experience in the state’s politics. Landrieu’s campaign advisers “do believe that her committee chairmanship is important for her re-election and they need to find a way to demonstrate what it really means.”

Likewise, in Montana, where Democrats are trying to hold on to a seat after the retirement of long-time senator Max Baucus, a denial of the permit could hurt the Democratic candidate. Montana lies on the pipeline route and has a growing energy industry. Top Democrats and Republicans in the state support the pipeline.

“If the President approved the pipeline or it remained unresolved, it would be the best hope for the President to neutralize the issue in Montana,” says Jeremy Johnson, a political science professor at Carroll College in Helena, Mon. “If he denied it, the Republicans might have some success in tying the Democratic candidate to the President.”

But a second theory is that in many of these conservative states, where Obama is bleakly unpopular, delaying the decision past the election would be more helpful than an approval for Democrats looking for issues on which to draw contrasts between themselves and the President.

In Alaska, for example, Democratic Sen. Mark Begich aggressively flaunts his independence from Obama—and in particular his disagreement with the White House over energy policy. “When the President calls me at times, I’m usually in his face about oil and gas issues,” Begich told Roll Call, a Capitol Hill newspaper this month. “When the administration as recently as a couple of days ago made a decision in an environmental impact statement, we’ll blast them to pieces if necessary.”

That ability to blast the President is helpful in the close race in Arkansas as well, where incumbent Democrat Mark Pryor is fighting off a strong challenge from Republican candidate Tom Cotton. “The issue [of Keystone XL] itself has low salience to most voters,” says Janine Parry, a political scientist and pollster at the University of Arkansas. “It’s the connection or the effort to distance himself from the President that matters.” Obama’s approval in the state is a dismal 27 per cent—and Pryor’s seat is considered likely the most vulnerable of all Senate Democrats. “If the President does not approve it, he gives Sen. Pryor the opportunity to rail against him—which is a net positive here,” says Parry.

The politics of Keystone XL are “Alice in Wonderland” and present a “twisted calculus” in the tight Arkansas race, she says. “Ironically, not approving the pipeline and giving the Arkansas Democratic senator the chance to chastise him for that might be the best thing President Obama can do to shore up the odds for a Democratic majority in the senate,” says Parry.

How hard does a conservative Democrat have to work to distance himself from Obama? “If there were an opportunity to have himself jumping up and down on Obama’s chest,” says Parry. “That would be a campaign win.”