The Melania Trump controversy? It’s out of Donald’s playbook.

In ‘The Art of the Deal’, Donald Trump explained how he manipulates the media. Now, it’s his campaign strategy.

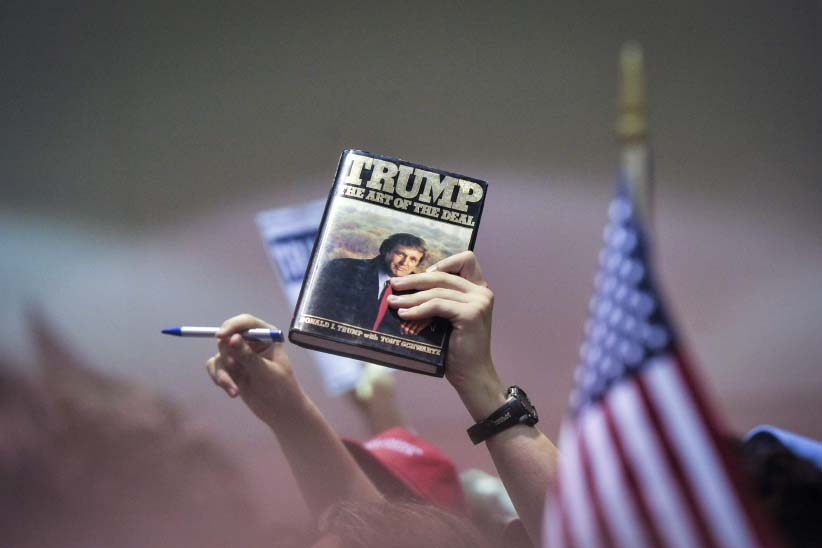

A supporter holds up book for signing by Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, who is the author, during a campaign rally held at the North Atlanta Trade Center, Saturday, Oct., 10, 2015, in Norcross, Ga. (John Amis/AP)

Share

So far the Republican National Convention has featured Congressman Steve King saying white people contributed the most to civilization, retired Lt. Gen. Michael Flynn saying Hillary Clinton should be jailed, and a new platform that includes a desire to break up big banks and eliminate nearly all campaign finance laws. All of this has been overshadowed by Melania Trump’s alleged plagiarism of Michelle Obama. The similarities between Melania Trump’s 2016 Republican National Convention speech and Michelle Obama’s 2008 Democratic National Convention speech dominated headlines across almost every major outlet in the United States and beyond Monday and much of Tuesday—thereby obfuscating everything else happening at the convention.

It’s unclear how Melania Trump ended up copying Michelle Obama. But it is clear the Trump campaign is relying on the explicit strategy he laid out in his 1987 book The Art of the Deal to make sure he gets as much free media coverage from what Melania did as possible.

In the book, Trump wrote: “Good publicity is preferable to bad, but from a bottom-line perspective, bad publicity is sometimes better than no publicity at all. Controversy, in short, sells.”

The Trump campaign has offered several different—in some cases contradictory—explanations for Melania Trump’s borrowing. A few hours before giving the speech, Melania Trump said, “I wrote it with as little help as possible.” On Tuesday morning, campaign spokesman Jason Miller credited a writing team, and Republican National Committee chairman Reince Priebus said he’d probably fire the person responsible for that section. Later in the day, Sean Spicer, the Republican National Committee’s chief strategist, drew comparisons between Melania Trump’s speech and words from a character named Twilight Sparkle on the popular children’s TV show My Little Pony. Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort accused Hillary, somehow. Finally, the Trump campaign announced no one would be fired.

Each pronouncement generated hundreds of headlines, many of them negative, but each comparing first lady Michelle Obama to aspiring first lady Melania Trump. Keeping the story alive by refusing to acknowledge it, and offering increasingly obstructionist and absurd explanations, is straight out of Trump’s 1987 handbook.

In The Art of the Deal, he wrote: “One thing I’ve learned about the press is they’re always hungry for a good story, and the more sensational, the better.” Later, he added: “Most reporters, I find, have very little interest in exploring the substance of a detailed proposal for a development. They look instead for the sensational angle.”

Headlines including the words “Twilight Sparkle” or “My Little Pony” draw eyeballs and advertising dollars for media companies, but they also provide free coverage for Trump. As of May 2016, he’d generated nearly $3 billion in free advertising, according to mediaQuant. His rival Clinton, meanwhile, got $1.1 billion in free advertising. As he put it back in October: “I can’t advertise because I’m getting so much coverage. It would almost be: you’d OD on Trump. You understand. That’s overdose on Trump.”

Trump habitually makes extreme statements to generate media coverage. Banning all Muslims and building a wall with Mexico are both nearly impossible, from a logistical standpoint, to pull off. Trump explained his logic behind these moves in 1987 too: “A little hyperbole never hurts. People want to believe that something is the biggest and the greatest and the most spectacular,” he added: “I call it truthful hyperbole. It’s an innocent form of exaggeration—and a very effective form of promotion.”