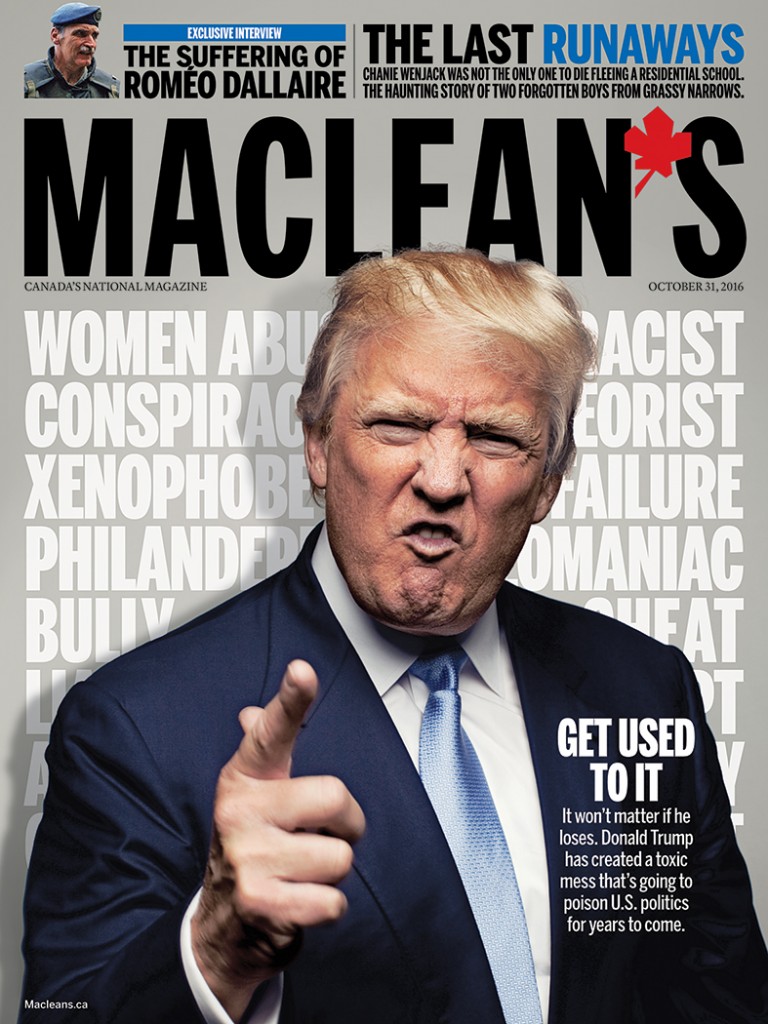

What will America do, after Trump?

No matter what happens, America will have to grapple with the toxic legacy of Donald Trump’s hateful, conspiracy-driven campaign

CANTON, OH – SEPTEMBER 14: Republican Presidential candidate Donald Trump greets supporters during a campaign rally at the Canton Memorial Civic Center on September 14, 2016 in Canton, Ohio. Recent polls show Trump with a slight lead over Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in Ohio, a key battleground state in the 2016 election. (Jeff Swensen/Getty Images)

Share

Donald Trump is a man without substance, but he has plenty of depths. Whenever it appears he has reached the nadir of his crass and hateful campaign for the White House, the New York billionaire sinks further. Often, several times in a single day.

As his presidential hopes plummet following the emergence of a 2005 tape where the then newly remarried 59-year-old bragged about sexually assaulting women, the Republican nominee has made it his mission to drag U.S. politics down with him. When nine women came forward with allegations that he had made unwanted advances, kissing and groping them, Trump called himself “the victim” and suggested his accusers are either hungry for fame, or not attractive enough to be credible. “Believe me, she would not be my first choice,” he said of one, to laughter and applause at a North Carolina rally. He announced a Third World-dictator-style plan to seal an election victory by appointing a special prosecutor to probe his Democratic opponent Hillary Clinton’s handling of classified emails, and regardless of the outcome, promised to put her in jail. Then during a Florida speech, he accused the former first lady of holding secret meetings with international bankers “to plot the destruction of U.S. sovereignty in order to enrich” her friends and donors—echoing, surely purposefully, the language of hoary anti-Semitic conspiracies.

The lies and distortions that have been the hallmark of Trump’s campaign have now given way to paranoid delusions. Over the course of just one week, he proclaimed that every mainstream media outlet in America—and almost all of the pollsters—are colluding to ensure his defeat. He declared war on his own party, denouncing Republican leaders like Paul Ryan as “disloyal,” saying they made “sinister bargains” with his opponents. He suggested that Clinton is taking stimulants to pump herself up and demanded she undergo a drug test before their final TV debate. And from both the stage and his Twitter bully pulpit, he made repeated claims that the coming election has been “rigged” against him. “Of course there is large-scale voter fraud happening on and before Election Day,” Trump posted on social media. “Why do Republican leaders deny what is going on? So naive!”

If one believes the polls—and judging from Trump’s behaviour, he certainly does—the reality-TV-star-turned-politician has already lost the Nov. 8 election. Clinton’s slim advantage in early September has widened to a yawning gap in mid-October, with some national surveys having her out front by as much as 12 per cent. On a state level, Republican bastions like Arizona, Georgia, Alaska and Utah are suddenly in play. The Electoral College tally is shaping up to be the largest Democratic victory since that of her husband, Bill Clinton. And if only either women or minorities had the vote, it would be a Hillary Clinton landslide.

Regardless of the outcome, however, Trump will leave behind a toxic legacy for American society. His campaign stew—two parts naked xenophobia with border walls and Muslim bans, a couple of cups of class resentment over trade deals and the economy, an unhealthy helping of sexism and a dash of “law and order” winks to white nationalists—leaves a bitter aftertaste. Republican legislators, divided amongst themselves, will find it harder than ever to reach across the aisle, ensuring four more years of Washington gridlock. And average voters, having grown accustomed to the months of insults, fantastical claims and conspiracy talk, now seem ready to believe the worst. To whit, a new Politico/Morning Consult poll showing that 41 per cent of all respondents—and a whopping 73 per cent of Republicans—agree that the election may indeed be “stolen” from Trump. (Little matter that he has never demonstrated the capacity to win it. Or that general elections in America are overseen by the states and administered by city and county governments, many of them Republican, making a national pro-Democrat plot awfully hard to organize. Or that a comprehensive study of one billion ballots cast between 2000 and 2014, conducted by a Loyola University law professor, turned up just 31 instances of “potential” voter fraud.)

Barack Obama, who has endured eight years of attempts to undermine his presidency from zealots who question his birth and religion—Trump chief among them—seems to despair for the future. During a speech in Ohio last week, he spoke about Greg Abbott, the Republican governor of Texas, who sent out the National Guard to observe a U.S. military training exercise last year on the basis that it just might be a dry-run for a gun-control takeover. “This is in the swamp of crazy that has been fed over and over and over and over again,” said the President, anger rising in his voice. And he blamed the Republican establishment for indulging such fevered fantasies in their quest for votes from the far right fringe. “Riding this tiger,” made a Trump run for the White House possible, Obama said. “If your only agenda is negative—negative’s a euphemism, crazy—based on lies, based on hoaxes, this is the nominee you get.”

University of Utah historian Bob Goldberg, the author of Enemies Within: The Culture of Conspiracy in Modern America, says there’s a long tradition of angst and apprehension in U.S. politics. “Conspiracy thinking is not unusual, not bizarre, not a matter of the extreme, but is rather mainstream and part of an American experience,” he says. Whenever the public’s faith or trust in authorities and institutions plunges, their belief in malevolent forces—from outside or within—rises. “It leaves you susceptible to what I call the Paul Reveres of American society, who are crying out ‘The dangers are here! The dangers are coming!’ ” says Goldberg.

While there have been a number of politicians who have trafficked in conspiracies in the past—Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunt against American communists in the 1950s is a prime example—Trump is the first major party presidential nominee to embrace the darkness. Goldberg says it might have been an inevitability after decades of wars and scandals—Vietnam, Watergate, Iran-Contra, Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction—steadily eroded public trust. (In the 1950s, 75 per cent of Americans said they believed their government would do what was right all, or most of, the time. Today the figure is 19 per cent.) But he wonders what comes next. “We have these real chasms, these gaps of wealth and race and ethnicity and religion. And they are not being bridged in any way. I don’t think that Hillary Clinton will be able to bridge them either. There’s so much hostility,” he says.

In that context, Trump’s claims that the fix is in when it comes to November’s vote could prove particularly dangerous. “If the basis of American democracy is compromised, you are in a situation where the people opposed to you are not simply wrong, they have committed treason, they are betraying the country,” says Goldberg. In some ways, it reminds the historian of the period just before the Civil War.

Related: In Donald Trump they trust

For foreign observers, one of the great mysteries about Trump is why he still has any supporters at all beyond white supremacists and women-haters. The months of revelations about his creepy personal past, his questionable business dealings and sham charitable activities would make him a political untouchable in most countries. (Canada’s tendency toward smug superiority should be tempered by two words: Rob Ford.) But the 35 per cent or so of American voters who are willing to go down with the SS Trump aren’t consuming the investigations and exposés that have enraged Democrats and fascinated the rest of the world. They’re living in a parallel media universe.

Breitbart, the “alt-right” website run by Trump’s campaign CEO Steve Bannon (he’s on leave for the duration of the campaign), is filled with stories that back up the Republican nominee’s narrative. “Rigged: Record number of Central Americans migrate into United States in 2016,” was one recent headline. “Putin denies meddling in U.S. elections, claims ‘U.S. spies on everyone,’ ” read another. Infowars, a conspiracy warehouse overseen by Trump-backer Alex Jones, is even less subtle, featuring claims like “Hillary called black servant the N word,” and “Bill Clinton’s rape victims fear for their lives if Hillary wins.” (Jones is behind the recent spate of protesters shouting rape allegations at Clinton rallies, having offered a US$5,000 “prize” for anyone who can get on TV for at least five seconds.)

Since the beginning of the campaign, Trump’s stump speech has featured a section where he complains about the “dishonest media” and invites supporters to boo the “horrible” reporters that he has corralled in the centre of the hall floor. The jeering provides a kind of catharsis for the crowd, à la pro wrestling. But lately, as Trump has pushed his allegations of bias, the anger has become real. CNN and NBC have hired security guards to watch their employees’ backs. And after a recent rally in Cincinnati, replete with chants of “tell the truth,” and middle-finger salutes, the press corps travelling with Trump had to be escorted to their bus by riot police.

America’s mainstream media is overwhelmingly for Clinton. As of mid-October, she had collected 147 endorsements from newspaper editorial boards, many of them staunchly conservative. In comparison, Libertarian nominee Gary Johnson had six, and the Republican nominee just two. There is no conspiracy, however, just a shared, evidence-rooted belief that Trump is spectacularly ill-equipped—intellectually, temperamentally and ethically—to hold the most powerful job in the world. Clinton remains deeply unpopular, viewed unfavourably by half the electorate. And the Russian-aided WikiLeaks hacks of Democratic Party emails have raised questions about campaign tactics and her own transparency. But few fear that she might launch a nuke in a fit of pique over an insulting tweet. Or oversee a genocide.

Related: Donald Trump in the time of terror

If Trump has a strategic plan for the final three weeks of the campaign, it’s impossible to discern. His daily rants about the women who have accused him of groping, and the unfairness of the media who insist on taking them seriously, keeps the focus firmly on his alleged assaults, rather than any promise or policy. And his contention that the election has already been stolen seems as likely to sap the spirits of his supporters as drive them out to the polls. Maybe he’s just stirring up anger and hoping for chaos. A transition from “only I can fix it,” to “I told you so.”

Trump is now globally famous, but his brand, once associated with aspirations and excess, has been drastically altered. No one is going to buy a steak, or bottle of cologne, or cheap Chinese-made tie with his name on it in hopes that it might make them appear classy. The same goes for condo developments. A planned golf course and residential complex in Dubai has already been scrubbed of his name and image. Bookings at Trump Hotels were down 60 per cent in the first half of the year. In September, the company quietly announced a new, Donald-less brand, Scion. Maybe it’s time to revert to the original family name—Drumpf.

What Trump is still able to deliver, however, is ratings, attracting millions of viewers whether they like him or not. This week, the Financial Times reported that Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, has been meeting with investment firms to try and drum up money for a Trump TV network. And while he might have difficulty finding sufficient backing for a cable competitor to Fox News—the start-up costs could be as much as $800 million—Trump could always create his own web empire, or simply syndicate his show to existing outlets. It makes a fair amount of sense, providing Trump with a way to maintain his celebrity and to influence American politics without the small paycheque and hassles of the presidency.

Could Trumpism survive with him trying to lead from the sidelines? The racial-nationalist strain of populism that the billionaire has been peddling has deep roots in U.S. politics, notes Michael Kazin, a professor of history at Georgetown University, rising during times of heightened inequality and economic fears. (Trump’s promise of an “America First” foreign policy parrots the slogan of an isolationist, anti-Semitic movement that flourished at the beginning of the Second World War.)

But Trump’s “movement”—as he likes to call it—has never been as well-defined as his predecessors’. The people he claims to champion don’t really have a “coherent, emotionally rousing” identity to rally round, says Kazin, just a shared anger. “Trump’s a showman. It’s unclear if he’s committed to the policies he talks about,” he says. Yet even if Trump fades, the broad concerns that drive his voters, like prosperity and immigration, are unlikely to disappear, at least in the short term. “These are important issues, and more popular, in some ways, than Trump himself,” says Kazin.

The United States is deeply divided. In his book, The Next America: Boomers, Millennials and the Looming Generational Showdown, Paul Taylor, the former executive vice-president of Washington’s Pew Research Center, talks about the rise of “alien tribes,” who “disapprove of each other’s lifestyles, avoid each other’s neighbourhoods, impugn each other’s motives, [and] impugn each other’s patriotism.”

But changing demographics will soon make selling those divisions less politically profitable. The country is rapidly becoming better educated, less religious and more diverse—by 2044, non-whites are projected to be in the majority. Trump’s campaign has sent the Republican Party even further down a dead end, appealing to an ever-shrinking base of white, conservative, and older voters, while actively repelling women, Hispanics, Asians and blacks. “This is a party that is facing a real reckoning going forward,” Taylor said in an interview with Maclean’s.

In fact, the Democrats are facing problems, too. According to the latest U.S. Census figures, there are now more Millennials than Baby Boomers. And while they skew liberal on almost every issue, Millennials are far less partisan than their parents, or grandparents. “They have grown up in an America where affiliation is not part of their identity,” says Taylor. A generation that holds high ideals, but places its faith in technology and each other, rather than greying leaders. “They simply don’t look to the political realm to solve problems,” he says.

Washington as it currently exists—gridlocked and constantly warring—therefore risks becoming more and more irrelevant to the lives and concerns of America’s citizens. Taylor figures the partisan fever has to break, sooner or later. “Political parties don’t commit suicide: they adapt or die.”

Could a Trump loss be what finally breaks the logjam? The beginning of the end of the politics of division? The 70-year-old has crossed so many lines, and broken so many taboos, that it’s hard to envision a future major party candidate pushing deeper into the swamp.Then again, it wasn’t that long ago that Trump was unimaginable too.