When did America stop being great?

The 2016 U.S. election cycle is all about urging America to be great again. Scott Gilmore disagrees with the premise.

Share

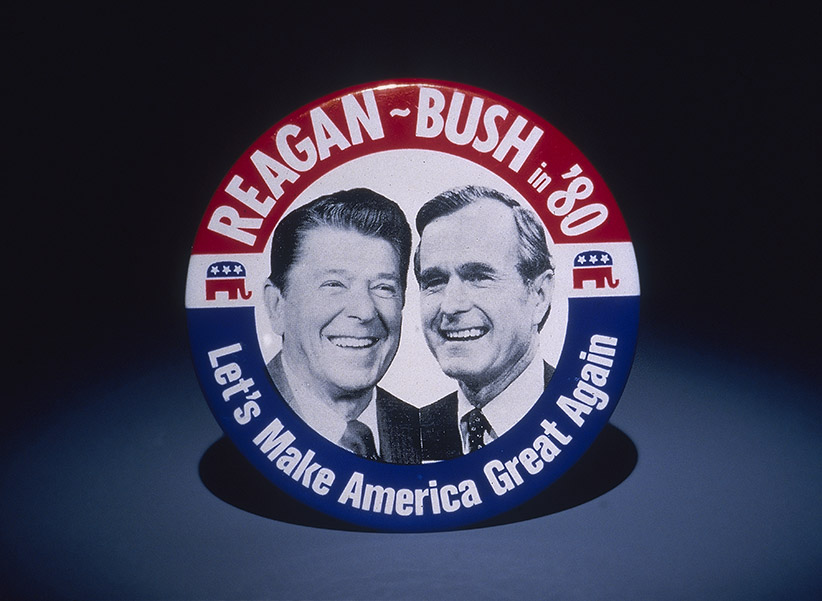

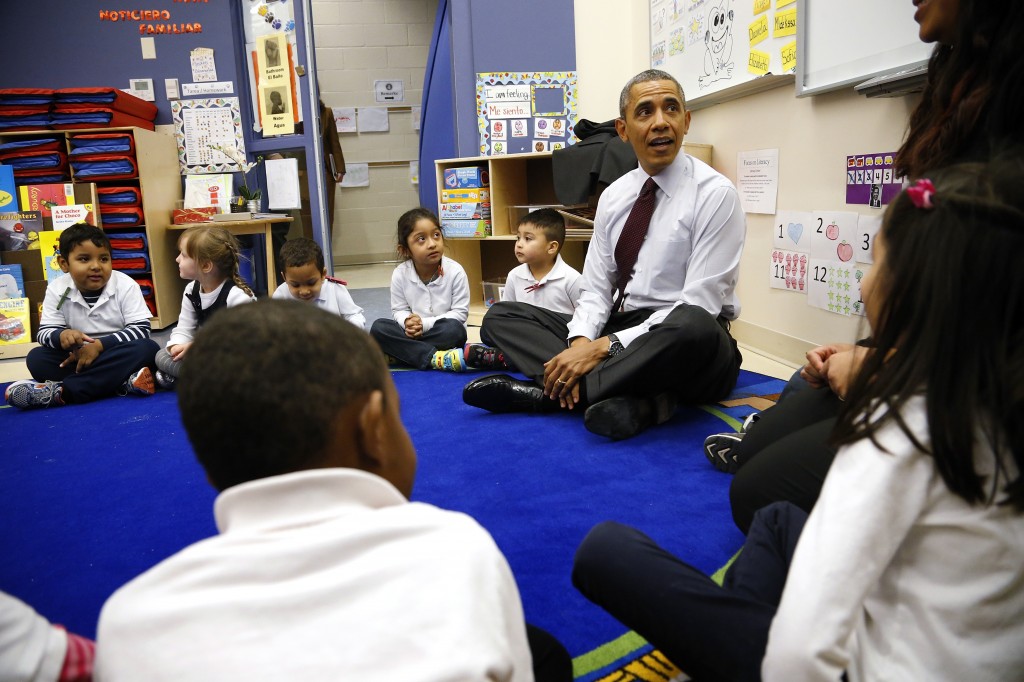

Every political challenger claims things have gone wrong and only they can set it right. In 2008, Barack Obama castigated the George W. Bush years and ran on the slogan of “Change.” In 1980, Ronald Reagan defeated Jimmy Carter by asking, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” Twenty years before that, John F. Kennedy was elected by promising, “We can do better.” And the loudest voice in this year’s election, Donald Trump, is asking voters to “Make America great again”.

But it’s not just Trump. Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz and the rest of the Republican field take it as a fact that America is in decline. On the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders paints a picture of a country plagued with systemic injustice and corporate malfeasance. With the sole exception of Hillary Clinton, all the candidates believe America is no longer “great.”

Are they right? Depends on which is more important, perception or reality.

There are three ways we can measure “greatness”: by calculating where America is now compared to before, by contrasting America to other nations and by considering how Americans see themselves. By the first measure, the United States has arguably never been better. By the second, its exceptionalism has clearly faded, but America still leads in many important metrics. By the third, Americans clearly don’t perceive themselves as great, possibly because the macro numbers hide decline amongst the middle class. And, in this election, it may only be the third measure that matters.

Let’s first consider America’s military power. The number of armed-forces personnel and the defence budget (as a percentage of GDP) has declined steadily since the 1950s, except for a spike during the Vietnam War. And the U.S. Navy has fewer ships than at any point since 1916. But these measures belie the dramatic improvement in military technology and doctrine. America’s military forces can do more, faster and farther, than at any time in history.

The relative position of the U.S. military is more complex. Russian forces declined after the 1980s, falling far behind the Americans in everything but nuclear weapons. By contrast, Chinese military spending has increased exponentially over the same period, tracking similar growth in its economy. As a result, America’s share of global defence spending is smaller than it was 10 years ago, but still more than in the last years of the Cold War.

Related: The U.S. establishment can only blame itself for Trump

But this is not how Americans see it. Protracted and messy counter-insurgency wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have produced few visible victories. There have been no flags raised over Iwo Jima. IED after IED, the belief in an invincible military has steadily eroded. Russia and China have one aircraft carrier each, while America has 19. Yet, according to a recent Gallup poll, only 49 per cent of Americans believed their nation is the world’s leading military power.

The question of America’s economic greatness is equally ambiguous. Over the long term, the objective measures are very positive. United States per-capita GDP has never been higher. The Dow Jones Industrial Average has grown 60 per cent in the past decade and is 1,400 per cent higher than 30 years ago. Exports are at a record level, up from nine per cent of GDP to 13 per cent since 1990.

But these mask shorter-term decline. Job creation is far below its historic pace. Labour-market participation is the lowest it has been since the 1970s. The number of apprenticeships fell by half over the past decade. Real wages have been flat for 40 years, and median household income has been stagnant for 20. The exception is the richest five per cent, whose incomes have increased disproportionately. And according to the Pew Research Center, the share of families living in middle-income households has fallen from 71 per cent to 61 per cent in the past 40 years. The Gini Coefficient, a measure of income inequality, has been rising steadily since the 1960s.

Relative to other countries, the American economy remains the strongest, but its lead is fading. In the Reagan years, the U.S. share of global GDP was 22 per cent; now it is only 16 per cent and falling. Some economists expect the Chinese economy to surpass the U.S. in just two years. China’s share of global exports is already larger. America remains among the best places to start a business, according to the World Economic Forum’s annual Competitiveness Report, but even that study flags high health and social-security costs as likely reasons for longer-term decline.

American perceptions of the economy are mixed. The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index score is currently not as good as it was 15 years ago, but it has been steadily improving since Obama’s election, and is now about average for the past 30 years. A recent Pew Research Center poll showed that while the number of Americans who believe the economic situation is good has increased since 2008, it is still at only 40 per cent. The top-line growth hides a lot of pain in the middle and lower classes. Which is probably why another survey reports that less than one in 10 Americans believe their children will be better off than they are.

What about American society more broadly? The narrative on the campaign trail is that the social fabric is in tatters. But the numbers don’t entirely support that. High school and college enrolment has never been higher. Teen pregnancy is less than half what it was 20 years ago. Gallup reports that over-drinking has declined to levels not seen since the ’70s. Support for civil rights has never been higher. Suicide rates are lower than they were in the ’90s (but up in the past decade). The homicide rate is lower than it was in 1910, and while the number of guns in circulation is at an all-time high, the percentage of households with guns is at an all-time low. And divorce rates are the lowest in generations.

But other numbers are less comforting. Divorce is down because marriage rates have also declined to an all-time low. Religious worship is at an all-time low. And the “war on drugs” has driven incarceration rates up sharply since the ’70s, but they are down since 2008 (they’re still four times higher than in 1970). And it has not succeeded: illicit drug use is up over the past decade.

Nonetheless, American society is still among the healthiest in world, if not the best. The United Nations’ Human Development Index, a measure of a health, education and standard-of-living indicators, ranks America eighth, behind Australia and a handful of European nations. The United States remains the most coveted destination for would-be immigrants and foreign students.

Nevertheless, the citizens of the United States are worried about the strength of their society. In the 1950s, 77 per cent of Americans trusted the government; it’s now 19 per cent. A majority believe that there is no clear solution to the biggest issues facing the country. And a majority believe America’s best days are behind them.

What about American culture? Mickey Mouse and Michael Jackson ruled the world in the 20th century. Is it still great? We can’t objectively judge if hip hop is an improvement on rock ’n’ roll, or if Matt Damon is better than John Wayne. But we do know Hollywood films are selling more overseas tickets than ever before and Furious 7 was the highest-grossing film in China last year. Nonetheless, the U.S. share of global box office revenue has declined as Asian and African films find their own audiences. Still, you could argue that with music, video games, films, books and TV, New York and Los Angeles remain (for now) the world’s leading cultural capitals. A recent Pew survey supports this claim, showing that global audiences continue to embrace U.S. pop culture and have grown even more positive over the last decade.

Admittedly, measuring America’s “greatness” is basically a parlour trick. Nonetheless, if America was great before, by most objective standards it is even greater now. Its military has never been more powerful. Its economy has never been bigger. And its society has never been healthier, more just or safer.

But by those same measures, America’s exceptionalism has declined. Many other countries have begun to catch up and even surpass the U.S. The Pentagon’s military supremacy is no longer completely unchallenged. The Chinese economy will soon become the world’s largest. And while America’s social indicators are among the best, many European countries (and Canada) now do better.

In spite of the facts, most voters believe America has lost its greatness, that it is a nation in decline. Which may explain Trump’s relentless march towards the White House. And maybe his supporters are right. By the numbers, it is unlikely Trump’s platform will improve the state of the union or America’s place in the world. But there is a chance his jingoism, bravado and bigotry will make many Americans believe they are great again. And maybe that is all they want.

Scott Gilmore writes on international affairs and public policy. He is a member of the Conservative Party of Canada and is married to Catherine McKenna, the minister of the environment.