Why Trump and Clinton really were the best America could offer

It’s become an accepted truism that Trump and Clinton were both terrible options for the 2016 U.S. election. But that may not be the case, after all.

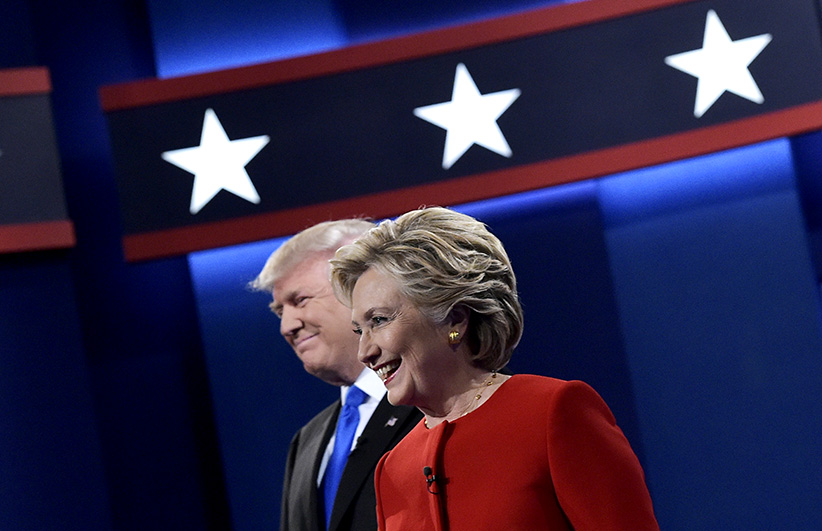

Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump(L) and Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton arrive on stage for the first presidential debate at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York on September 26, 2016. (Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images)

Share

If there’s one thing we all know about this U.S. election, it’s that the two major parties picked the worst possible candidates. Frequently, polls showed that Americans thought both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump would be terrible presidents, or that they were the “least trusted candidates in modern history.” It’s easy to conclude, as South Park recently did, that Clinton was the only person who could possibly lose to Trump, and vice-versa.

But could other candidates really have done better for the Democrats than Clinton? And would any of the available Republicans have performed better than Trump? If the candidates had been Barack Obama running for a third term, and the ghost of Ronald Reagan, maybe. But though it may sound scary, there’s a case to be made that both parties’ primary voters picked the strongest candidates available to them—at least from the point of view of their ability to win the election.

A lot of election coverage portrayed Clinton as a deeply unpopular politician, but she isn’t. Her approval ratings have fluctuated over the years, but she was a popular U.S. senator and a popular secretary of state. Her ratings go down after she’s engaged in partisan combat, like her race against Barack Obama or Bernie Sanders for the Democratic nomination—but that’s hardly a problem that’s unique to her. Some observers were disappointed that Vice-President Joe Biden decided not to run for the presidency. But Biden’s approval has fluctuated a lot too, and he’s famous for his constant gaffes (like the time in 2007 he described Obama as “the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean”). He might have been the one Democrat who could have distracted the media from Trump’s gaffes.

The other option, of course, was nominating Bernie Sanders, who would have been better-positioned than Clinton to respond to Trump’s populist appeals. But Sanders lost the nomination in part because he had trouble appealing to African-Americans, who make up one of the most important parts of the Democratic base. Sanders might have had more crossover appeal to potential Trump voters, but that couldn’t have made up for the black voters who might have stayed home if he’d been the nominee.

And speaking of voters staying home, Trump’s candidacy may have helped the Republicans mobilize the so-called “missing white voters,” the white working-class men without college degrees who have become a key part of the party’s base. Trump’s appeal to these voters has helped him do well in heavily working-class states that Obama won twice, like Ohio and Iowa. To assume that a candidate like Mitt Romney would have performed better than Trump, one has to assume that these voters would have been equally happy to vote for Romney. But a lot of them didn’t like Romney, and were only enthusiastic about a protest candidate who stood against the Republican establishment. From a practical rather than a moral standpoint, Trumpism was always the best shot at wringing one last victory out of an old, white party.

But the main reason both of these two people were the strongest candidates available: their parties don’t have a lot of good political talent. This is more obvious on the Democratic side, where Clinton was able to run almost unopposed (until the long-shot candidacy of Sanders started to gain steam) because her party doesn’t have any new Barack Obamas or Bill Clintons. Thanks to the Democrats’ dismal showings in mid-term elections in this decade, there aren’t a lot of Democrats who are recently elected senators or swing-state governors. That leaves Clinton as almost the last Democrat standing.

It was supposed to be different with the Republicans, who had so many seemingly qualified candidates that there were once many articles praising the “deep Republican bench.” Only it turned out that almost all these people were unacceptable to Republican primary voters on the issues they cared most about—particularly immigration. Some of them, like Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, changed their immigration positions to compete with Trump, but that just reinforced Trump’s portrayal of normal politicians as feckless hacks.

Most of those Republicans were trying to run on the Ronald Reagan playbook, combining economic libertarianism with social conservatism and foreign-policy hawkishness. Trump beat them—because that playbook led to the Republicans losing most presidential elections since 1992.

The work for both parties in the future will be to create the type of candidates who can do better. The Democrats will need to fix their weaknesses at the state level, producing more politicians like Bill Clinton, whose experience as governor of a conservative Southern state taught him to appeal both to the Democratic base and swing voters. The Republicans will need to find politicians who can appeal to white working-class interests without Trump-style xenophobia and white identity politics.

In 2016, there weren’t any politicians available who clearly could have outperformed Clinton or Trump. That may be the biggest indictment of the current state of U.S. party politics.