Women in the House: The decline of the female power player

We analyzed decades of female representation and found what matters is electability and power conferred once in office

Green Party Leader Elizabeth May, centre, is flanked by local candidates while speaking during a campaign event in Vancouver, B.C., on Wednesday September 9, 2015. A federal election will be held October 19. (DARRYL DYCK/CP)

Share

A week today is the deadline for the final candidate count, the day we’ll know how many women are running for federal office in 2015. The NDP’s slate is already in: it’s close to half (43.5 per cent) women. With two per cent of its ridings unresolved, the Liberals stand at 31.3 per cent. The Conservatives are just shy of 20 per cent (at 19.7), with 96 per cent of ridings decided; the Greens have one-third (32.7 per cent) women with 73 per cent of ridings reported. As tempting as it is to take these numbers as biomarkers of party progressiveness and diversity—or lack thereof—that would be a mistake. As our analysis of female representation in Parliament and cabinet makes clear, size (as in total number of women running) doesn’t matter. What does is performance: electability and, more crucially, power conferred once in office.

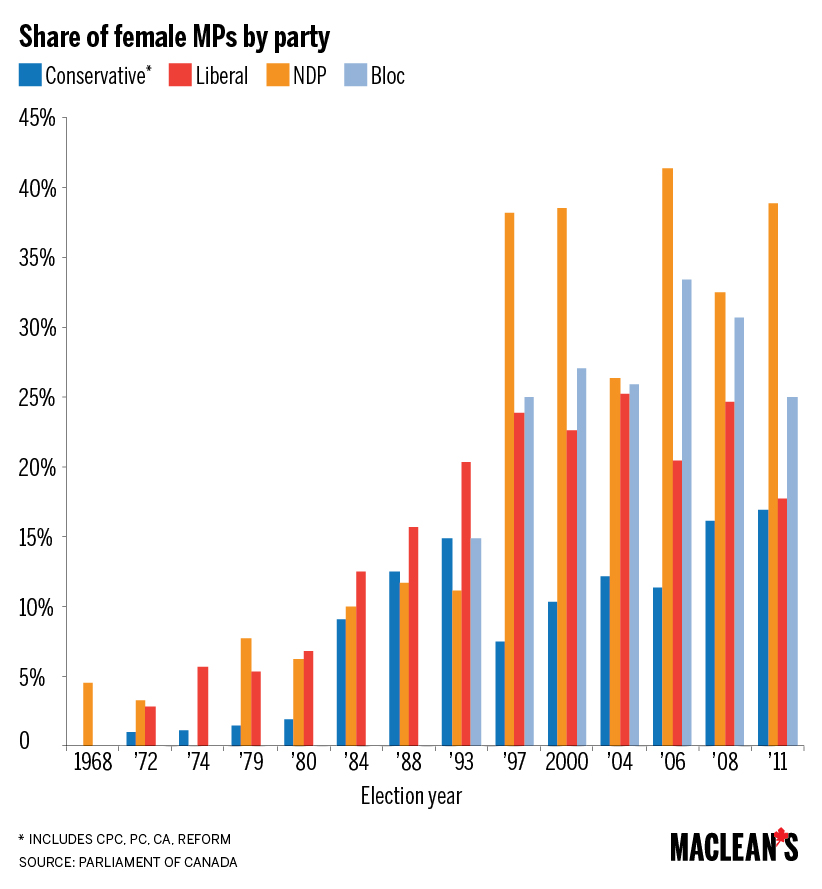

NDP numbers reveal that story.

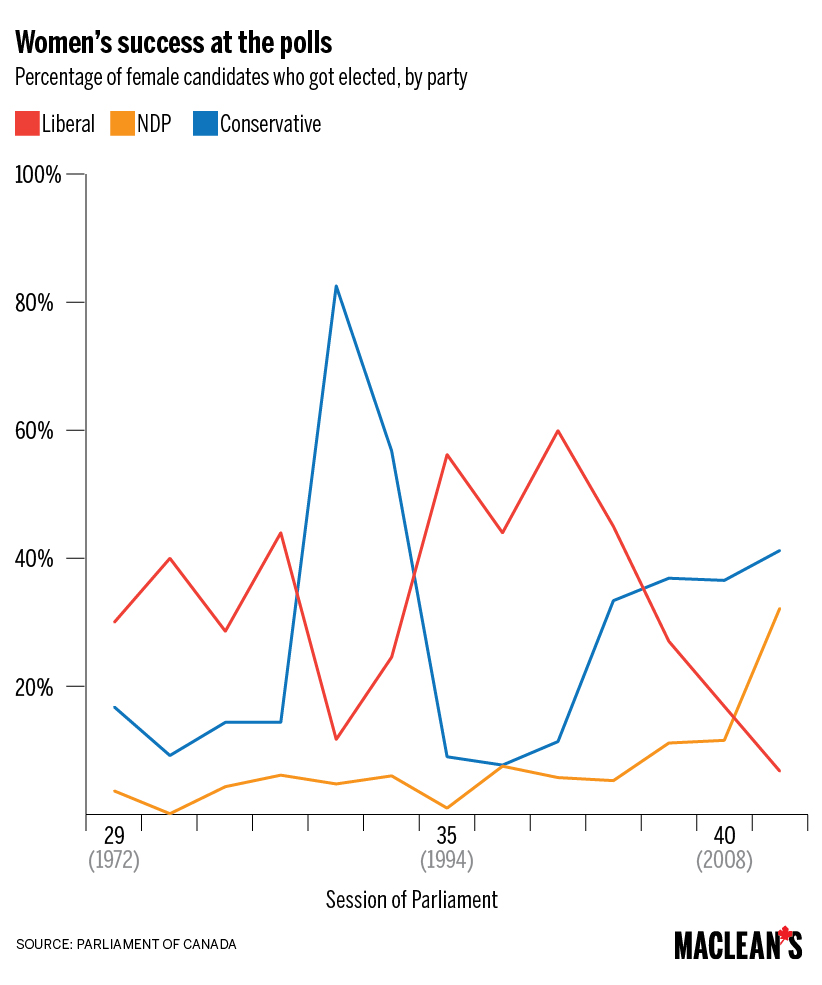

The party has historically had the highest proportion of female candidates. Yet until the 2011 Orange Wave, which saw 32.5 per cent of female NDP candidates elected as well as a record number of women voted to Parliament, women running for the party had the lowest odds of ending up in question period. In 1993, an election that attracted a historic all-time high of 476 female candidates, 113 women ran for the NDP; only one was elected—0.9 per cent. Meanwhile, 64 women ran for the Liberals, which formed the government that year; 34 of these, or 56 per cent, won seats.

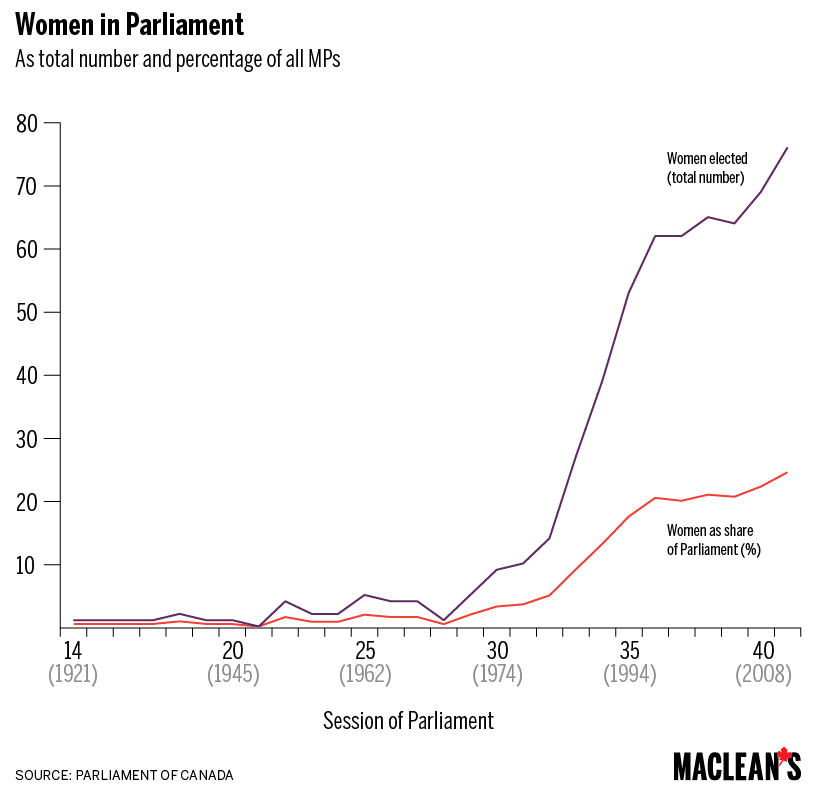

To see how this trend plays out over time in the makeup of Parliament, consider the following chart, which tracks the disconnect between the rise in the number of women elected and female representation in Parliament. That percentage stands at 25, putting Canada at a sorry 50th place on the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s “List of women in national parliaments.”

The 1993 election was also the first (and only) to feature a female prime minister, Kim Campbell, who won the Progressive Conservative leadership in June at a time when the party was deeply unpopular (it’s not unusual for organizations in crisis to bring in a woman to suggest radical overhaul). Connecting dots between a woman achieving the top political job and record female participation in that election isn’t difficult.

What we saw following the defeat of the party (and Campbell) in a landslide Liberal victory was a steep reversal in a (more or less) steady rise in female participation in the parliamentary process since the election of Agnes Macphail, the first female MP, in 1921, the first time women could vote federally. Five women ran that year. We saw a big leap in 1953 when 46 women ran (up from 12 in 1949); four were elected. Looking at female representation in Parliament by party is also revealing. Since 1968, as the following chart shows, the NDP has consistently had the highest proportion of female MPs of all the major parties.

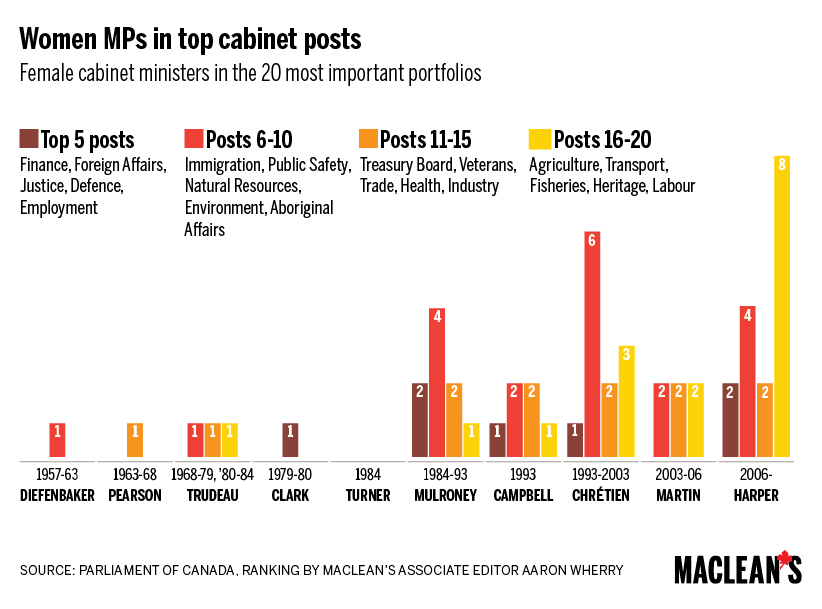

It’s instructive to look at female representation (or lack thereof) in cabinet, the apex of power in parliamentary democracies. Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau has made the topic an election issue, promising gender parity in cabinet. Imposing quotas is a contentious topic in the corporate arena, with calls for, and even legislation mandating, greater gender parity on boards (women hold just under 20 per cent of seats on Canadian boards). In government, it’s one thing to appoint women to cabinet, another to appoint them to powerful positions. To see how women have fared by the latter metric, we ranked the top 20 cabinet positions in terms of importance of ministry (it’s a subjective list; Health, for instance, is ranked at 17th based on the priority given to it by the current government and the fact that health remains a provincial concern).

Our analysis dates to 1958, when John Diefenbaker appointed the first female cabinet minister, Ellen Fairclough, who was secretary of state, minister of citizenship and immigration, and postmaster general. Tellingly, no woman has held the top-ranked spot, Finance (women have held top Finance positions provincially since the late ’70s, but that has not translated federally). Nor has a woman held the Agriculture portfolio.

The above bar chart also reveals that the days of women holding primo power cabinet positions are far in the rear-view mirror. The first power player was Flora MacDonald, named to Foreign Affairs in 1979—making her the first woman to represent Canada on the world stage, and a trailblazer internationally. MacDonald was appointed by Joe Clark, who won the 1976 Progressive Conservative leadership that everyone assumed MacDonald would walk away with; her support evaporated when it came time to vote—a phenomenon dubbed the “Flora Syndrome.” It’s also worth noting that Kim Campbell held dual power cabinet positions of External Affairs and Defence before winning the leadership.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

None of the four top-ranked positions have been filled by a woman since 2003. Diane Findley held number five, the Employment portfolio, as Human Resources and Skills Development, between 2008 and 2013. One can argue—and academics have—that cabinet positions tend to reflect larger gender bifurcation, with women given “softer,” more “domestic” portfolios. Ironically, these so-called lesser portfolios profoundly affect how we live: Environment, Health, Heritage, Culture and Communications. In their 2005 study, “Representation of Canadian women at the cabinet table,” Linda Trimble and Manon Tremblay assessed cabinet postings held by women in municipal, provincial and territorial, and federal cabinets between 1917 and 2002. Being female helped and hindered, they conclude: “Sex may on occasion have benefited women legislators when seeking cabinet appointments but it has also affected the type of ministries women receive.” Women “continue to be appointed in greater number to social activity portfolios than do men, who tend to receive more appointments in the defining activity and physical resource mobilization categories.”

Put more plainly, women get the “nurturing portfolios,” which, by definition, are seen as “intrinsically less prestigious, important and career-enhancing.” While Trudeau’s gender parity plan has received attention and debate, he’s proposing an even bigger potential change-maker to female representation in Parliament: his vow to bring in preferential ballots, or proportional representation. While electoral reform may make people’s eyes glaze over, one need only look to European parliaments—hello, Angela Merkel—to see the results. Studies point to proportional representation being key to female political advancement, Sylvia Bashevkin writes in Opening Doors Wider: Women’s Political Engagement in Canada, published in 2009. We’re still living with the “Flora Syndrome,” she says: “Women plus power equals discomfort.” But, as the charts show, that’s only because women plus power remains the exception.

—Data compiled and analyzed by Patricia Treble