After the call: What the Trump fracas did to Malcolm Turnbull

A bad chat with Trump put Turnbull in the world news. What happened next is telling of an unpredictable president’s domestic impact

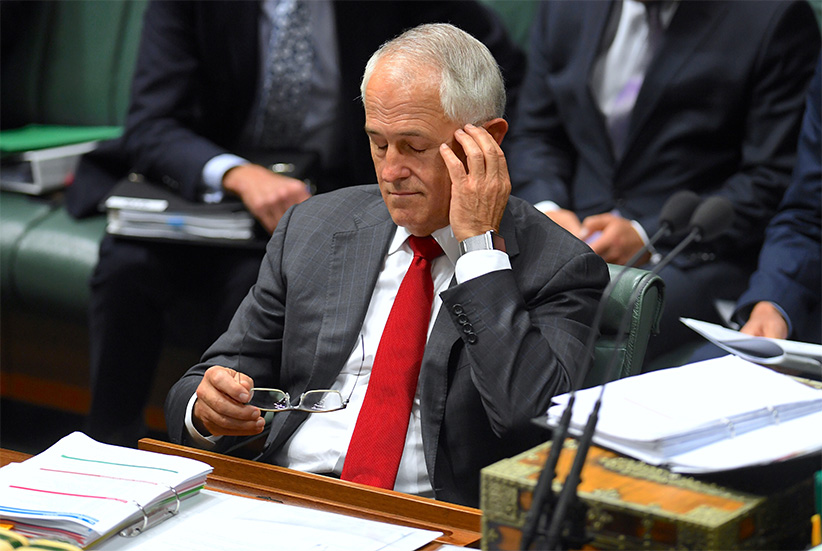

Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull reacts during Question Time in the House of Representatives in Parliament House, Canberra, Australia, February 7, 2017. (Lukas Coch/AAP/Reuters)

Share

In every one of the 116 years since the nation was born, Australia has been content to walk in the shadow of great and powerful friends: first as a branch office of the British Empire and steadfast representative of the white race in Asia, and later as an equally stalwart ally of the United States. For decades, the fear of communism and the menacing hordes to the north guaranteed Australia’s fealty to Washington. The practical and ideological supports of the alliance merged happily in the cause of freedom.

Not any more. The end of the Cold War did not end the alliance, but the case for it is no longer so easily made. The Domino Theory simplified the world: the War on Terror makes it murkier. And China, Australia’s primal fear, is now vital to her future prosperity. Each year it grows harder to navigate a path for the alliance, and the words that once galvanized it no longer so readily apply.

For the comforting reassurance that comes with being Washington’s dutiful deputy, Australia pays a price. Along with the blood and treasure expended on imperial battlefields, a degree of self-possession must be sacrificed. The security and convenience of walking in the shadow of the sheriff is accompanied by a debilitating sense of being America’s “long-time poodle-dog ally,” to use Bill Maher’s recent description. In such a relationship the weaker party is tempted to shore up its identity by exaggerating the influence it has, or by singing a descant to the anthems of the stronger partner, as if both countries were answering a ‘call to greatness,” or some other demand of destiny dreamed up by David Brooks.

As anyone who has worked in a political office knows, speaking to the powerful is a skill, and that speaking unwelcome truth to them is a skill of a very high order. This is only partly because many powerful people are insecure, ill-tempered and unreasonable, many have been corrupted by power, and for all their success in politics, not a few are stupid. It is also because the meaning and purpose of power is force. However enlightened or kindly power might be, force arises from it. Those subjected to force become something less than themselves: as Simone Weil said in her famous essay on this subject, very often they become corpses.

While we might never know exactly what was said when the Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull spoke with Donald Trump on the phone earlier this month, we can be sure that the force was with Trump. With Turnbull lay the hope that he would come out of the conversation much as he went into it, and not as a corpse or a poodle. But hope is not enough when you’re presenting the President of the United States—any President—with an unpalatable fact.

The fact in question was a deal between Turnbull and Barack Obama signed five days after Donald Trump won the U.S. election. Obama agreed that the U.S. would take 1,200 of the 2,000 asylum seekers who have been languishing for years in camps administered by Australia on Nauru and Manus Island in Papua New Guinea. The people in these hellholes had been intercepted by Australian naval vessels as they tried to cross from transit camps in Indonesia to the northern coast of Australia in dilapidated fishing boats. Many hundreds on these desperate voyages had drowned. The island camps were set up when the Australian government declared that no one arriving in this unauthorized way would ever be settled in Australia, and directed the navy to turn back all boats. The boats promptly stopped, but the policy and the camps have poisoned Australian politics and, in some quarters, its reputation.

For Malcolm Turnbull, the Obama deal was a chance to drain the abscess without looking like anything less than resolute on “illegals” or “queue jumpers.” Since coming to the Prime Ministership in the guise of a genuine liberal, Turnbull has been mauled by the right wing of the governing coalition, not least by the man he ousted as PM, Tony Abbott. An election Turnbull called last year to win more legitimacy left him with less of it—a one-seat majority in the House of Representatives, a Senate with a new cohort of xenophobes and Trump admirers under the banner of One Nation, and an ever more persistent need to satisfy Abbott’s crew of sea-green reactionaries who have recently taken to calling themselves “the deplorables.”

For a Prime Minister on the skids, the deal with Obama was a godsend. For Donald Trump, it was “dumb,” the “worst deal ever.” He had a point. Just as he bans entry to people from seven predominantly Muslim countries, he learns that Obama has signed up to take “thousands” of mainly Muslim asylum seekers, many of them from the same seven countries. Faced with the exquisite predicament of having to ask the world’s most powerful human being to accept the world’s worst deal, Turnbull tried to find common ground in the spirit of the alliance and the rules of business (before entering politics, he made a fortune at Goldman Sachs). A “deal is a deal,” we’re told he ventured. But Trump didn’t buy it.

MORE: Why the Trump-Turnbull beef should actually be a bromance

Later, while Turnbull invoked old protocols and refused to disclose what was said in the call—except that as always in a friendship as ‘mature’ and ‘robust’ as ours, etc., it was “frank and forthright”—the President’s office let it be known that the conversation was the “worst” the President had had and that it ended badly. The President followed up with a tweet: he would be looking hard at the deal, and should he decide to honour it, the detainees would be subjected to “extreme vetting.” Then the White House referred to the Prime Minister as “President” of Australia, and by the time the Press Secretary called him Mr. Trumble and Mr. Trunbull, and Bill Maher came up with the poodle, Malcolm Turnbull’s humiliation was pretty well complete.

U.S. commentators, politicians and the regiment of American satirists rounded on Trump for attacking a loyal and harmless friend, and the Australian press, as they often do, made the reaction in the U.S. to something involving Australia their main story. But more intriguing by far was the effect the phone call seemed to have on Turnbull. Worsted in an unwinnable battle with the world’s greatest bully, he went into the Parliament and bullied the leader of the opposition in a tirade described by some as “withering” and by others as “vile.” That the gist of the attack concerned his opponent’s “sycophantic” friendship with a billionaire seemed to offer a clue to his motives and to the psychological damage the phone call had done. “I stand up to billionaires,” he later told the press. “I look them in the eye and, when I need to, I take them on.” It seemed to prove that Malcolm Turnbull had indeed shrunk to something less than himself.

Since then, Abbott has intensified his attack on him, and in a manoeuvre surely inspired by Donald Trump’s belligerent example, Senator Cory Bernardi has defected from the government and formed a new “Conservative Party.” Now trailing in the polls by a greater margin than his predecessor ever did, Malcolm Turnbull has taken to lecturing journalists who pay too much attention to “personality politics.” So far he has not used the term “fake news,” yet.

Arrangements are now being made for Turnbull and Trump to shake hands on the deck of a U.S. battleship in New York harbour in the first week of May. The pretext for the photo opportunity is the 75th anniversary of the U.S. Navy’s success in the Battle of the Coral Sea, an action which Australians have long believed saved them from Japanese invasion. It is sure to be said that the handshake symbolizes the importance and enduring strength of the alliance, and how straight-talking is the hallmark of all great friendships—but the possibility remains that the President will break Turnbull’s wrist, and that will symbolize something else entirely.

Don Watson, a former speechwriter to the Australian Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating, writes about Australian history, politics, culture and language, and occasionally about the United States. His recent works include The Bush (Penguin) and Enemy Within (Black Inc.), on the 2016 U.S. election.