Putting Putin’s army to the test

The war in Ukraine is the first real test of Putin’s new and improved military. Why its early successes should make Russia’s neighbours nervous.

Members of the Guard of Honor of the Presidential Regiment from Russia perform on the first day of the International Military Music Festival “Spasskaya Tower” in Red Square in Moscow, August 30, 2014. Military bands from different countries will participate in the tattoo starting from August 30 to September 7. MAXIM ZMEYEV/Reuters

Share

Ukrainians suffering as a result of Russia’s ongoing invasion of their country might want to blame Georgia. The small, former Soviet nation in the Caucasus bears no direct responsibility for Russia’s attack on Ukraine, but in many ways Georgia’s own war with Russia in 2008 helped make it possible.

In less than a week that August, Russian forces, along with their South Ossetian and Abkhaz allies, appeared to have routed the Georgian military—driving it, along with many ethnic Georgians, from the contested Georgian territory of South Ossetia and pushing deep into the rest of the country. A couple of weeks later, Russia effectively annexed both South Ossetia and Abkhazia (the territories have officially declared their independence).

For much of the outside world, the war was a shocking demonstration of Russia’s new post-Soviet aggressiveness and willingness to use military force beyond its borders. For Moscow, the war was traumatic for other reasons. Russia achieved its objectives, but at a higher cost than it had anticipated.

More than 60 Russian service personnel died in the campaign and its immediate aftermath. Moscow also lost six aircraft, according to an essay by analyst Anton Lavrov published by the Moscow-based Centre for Analysis of Strategies and Technologies. Of these, Lavrov says, at least three were shot down by “friendly fire,” starkly revealing the poor command and control logistics of Russia and its allies. Other exposed weaknesses included vulnerable armour and trucks, the slow movement of troops and poor communications. “They won that war. They didn’t like how they won it,” says Olga Oliker, director of the Center for Russia and Eurasia at the Rand Corporation.

As a result, Russia accelerated a massive process of military reform. “It is the first time in Russian military history that authorities learned lessons not from failure, but from victory,” says Alexander Golts, a Russian journalist and the author of two books on Russia’s military since the collapse of the Soviet Union. “It was a tremendous reform—a total rejection of the concept that ruled Russian forces for 100 years, and a rejection of the biggest part of Russian and Soviet military culture. Because all this culture is based on the idea that we will prevail over our adversaries with the number of troops.”

Gone was the lingering Cold War idea that Russia would break the back of NATO in massed tank warfare across Central Europe. Gone too was faith in the untold thousands of thousands of conscripts who could be called up to overwhelm opposing armies. “This is the way we won the war against Hitler,” Golts says. But Hitler had been dead for 60 years, the Berlin Wall had fallen, and no one in the Kremlin really thought NATO would send its tanks rolling through Eastern Europe anymore.

Russia’s new military doctrine called for a smaller, better-trained and nimbler force that could be deployed quickly and perform complex tasks. Achieving this was the job of then-defence minister Anatoliy Serdyukov, a former furniture salesman who, like so many current and former allies of President Vladimir Putin, once lived and worked in St. Petersburg. Aside from a brief spell in the army following university, Serdyukov was not a military man.

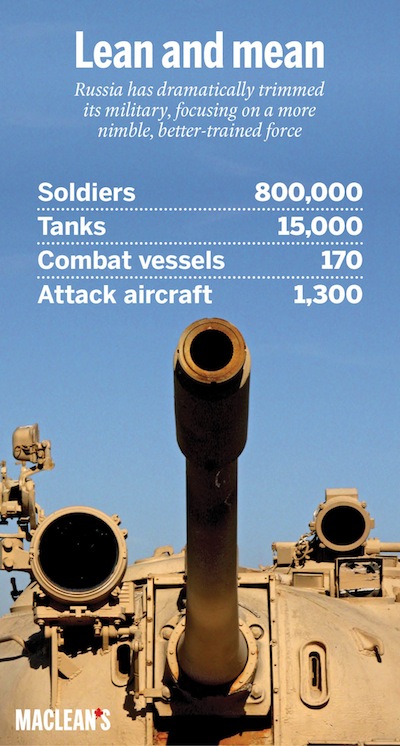

“He had no institutional axes to grind, precisely because he wasn’t an insider,” says Mark Galeotti, a Russian security specialist at New York University. “He could come in and do all the savage stuff that needed to be done.” Serdyukov drastically cut the army’s officer corps and reduced the overall size of the military from some 1.2 million to about 800,000.

Any opposition to Serdyukov from Russia’s military brass was at least softened by Putin’s political support, and by the hundreds of millions of dollars Putin poured into the military. There was money for equipment, flying hours, bases and salaries. According to Keir Giles, an associate fellow at the Chatham House think tank in London, living conditions, pay levels and, as a result, the basic morale of soldiers, were “absolutely transformed.”

The real test of a military, however, is war. Russia would get one six years after the Georgia conflict.

The transformation of Russia’s military was not complete by the time “little green men” without insignia on their uniforms showed up in the Ukrainian region of Crimea last year, following street demonstrations that forced out the pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych. But it was well under way. Today, it is a different Russian army—even one whose presence is officially denied by Moscow—that Ukrainian troops battle in the east of their country, where a Russian-backed insurrection threatens to split Ukraine in two. “Whenever we’ve seen serious deployment of Russian forces in Ukraine against Ukrainian regulars, to be perfectly honest the Russians have just chewed through them,” says Galeotti.

Ukrainians are witnessing the ongoing repercussions of Russia’s 2008 war in Georgia. It’s a Russian army with new capabilities. It’s also one more in tune with the sorts of wars the Kremlin believes Russia will be fighting in the future.

Russia still sees NATO as a primary threat. But it is one they realize they can’t beat in symmetrical warfare because of the combined strength of the alliance’s members, led by America, says Paul Schwartz, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. In the unlikely case of a direct and full-scale confrontation, Russia will rely on its nuclear deterrent.

What Russia most fears from NATO is interference in countries it considers to be within its sphere of influence, and in Russia itself. “The threat that the West presents to Russia is democracy,” says Stephen Blank, a senior fellow for Russia at the American Foreign Policy Council. “To them, the biggest threat is the sponsorship of democracy promotion or ‘colour’ revolutions.”

Russia also recognizes threats posed by potential upheaval along its southern frontiers, especially in the Caucasus, where the wars in Chechnya were long and costly. There is another threat, from China, that Russia rarely acknowledges publicly, but for which it also relies on a nuclear deterrent.

But to deal with insurrections or popular protest movements in its near abroad, Russia believes it requires well-trained, fast-moving troops. This is the military that Moscow is building. According to Golts, Russia’s greatest military accomplishment in recent years wasn’t the seizure of Crimea, which involved small numbers of elite troops, but the rapid deployment of regular forces to Russia’s border with Ukraine last March.

“When you can deploy 50,000 men in two days, it’s tremendous for the Russian armed forces,” he says, comparing that deployment to Russia’s slow response to a 1999 invasion of the Russian republic of Dagestan by Chechen militants. But there is another side to Russia’s reforms, says Golts. Moscow’s new army was designed to win quickly and go home. “If you deploy them for a year, you see these forces are exhausted.” Russia’s intervention in eastern Ukraine, which shows little sign of ending, is putting strain on Russia’s military, he says.

The reforms have also been expensive. With Russia’s economy hit by a combination of Western economic sanctions and dropping oil prices, it has less money to pay for them. “Putin’s plans were very much predicated on the situation in his first two [terms], when everything was going his way,” says Galeotti, referring to the years between 2000-08. “The West was distracted post-9/11; the economy was booming because of oil and gas prices; the elites were bought off; and he still had lots of money left over to buy shiny new toys for his military. He didn’t have to make any hard decisions. Now, in his third term, when arguably he’s become much more nationalist and even xenophobic, this is when he needs to make hard choices.”

Unfortunately for Russia’s neighbours, Putin is unlikely to choose to scale back his ambitions abroad. An aggressive foreign policy has helped him politically, and it is something he personally believes in. Putin laments Russia’s lost clout and prestige and is trying to rebuild it.

Countries geographically close to Russia that are not part of NATO, such as Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova, are most at risk. Although NATO counties such as Canada are not obligated by treaty to help them, Galeotti believes it is in the interests of Western nations to do so. “Putin despises the current international order. He regards it as a Western system build to protect Western interests. Unless we’re willing to go back to a period of primal geopolitical anarchy, we need to be in a condition to provide some sort of teeth—maybe through sanctions.”

NATO member states are less likely to be the targets of overt, or thinly veiled, invasions. But they still may be vulnerable to elements of “hybrid warfare” involving economic and diplomatic pressure, disinformation and cyberattacks. NATO member states with large ethnic Russian minorities, such as Estonia and Latvia, are especially concerned.

Here, according to Galeotti, the best defence against potential Russian interference may not be military. He describes a visit to Estonia in which a defence official insisted his country needed more tanks to defend against Russia. Galeotti countered that what Estonia most needed were more intelligence officers, police and social workers to help integrate the country’s Russian minority. “We need to ensure that we have forces that meet the real threat, rather than the ones that generals enjoy countering.”

It’s an approach Oliker describes as reducing vulnerabilities. Ukraine was exposed to Russian subversion, she says, in part because it had been so badly and corruptly governed for 20 years. Helping countries of the former Soviet Union grow their economies, diversify their energy sources and integrate their Russian populations makes them harder targets.

Putin, meanwhile, will continue to dump Russia’s money into its armed forces. He missed an opportunity to invest in the country’s infrastructure and diversify its economy when high energy prices meant he could, says Galeotti. Now it may be too late. Putin has doubled down on making Russia strong militarily, which may end up corroding his own political power.

Putin is in a bind. If he reverses course, he will anger Russia’s many nationalists, whom he himself has emboldened. Continuing means draining money away from other public services, and that, too, has a political cost. “Let Putin burn through his money. There is a way that Putin is spending his way into an early political grave,” says Galeotti.

Maybe. But he’s not there yet. He’s wildly popular in Russia in no small part because of Russia’s military adventures abroad. And now he has the sort of army he needs to undertake more of them.