Scott Gilmore faces his harshest critics

Our columnist called up some of the angriest opponents of his refugee plan. Underneath the abuse, he found, were some legitimate fears.

Share

This was more rewarding than it sounds: After writing a series of controversial columns, I decided to personally contact some of my angriest critics.

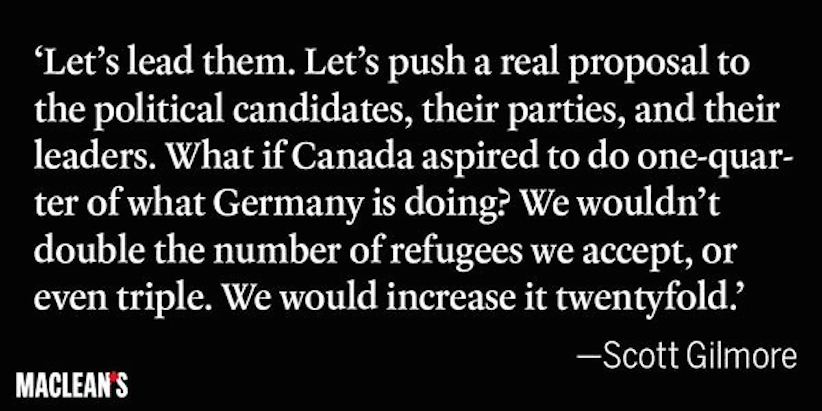

For the past two weeks, in Maclean’s and on radio shows across the country, I have been arguing that Canada should take 200,000 refugees during the next 12 months. This sparked a backlash that was occasionally polite, but usually emotional and angry. I’ve been called worse names, but not often.

The majority of people who reacted to my proposal supported it, which reflects a broader view in Canada that we’re simply not doing enough. A recent Forum Research poll reported that 52 per cent of Canadians thought we could do more than what the government is proposing. An Angus Reid poll found a similar number. But both polls also revealed that a significant minority of the country is opposed. Almost a quarter of respondents in the Angus Reid survey said Canada should do nothing and, in the Forum Research Poll, 38 per cent disagreed that Canada should do more.

This isn’t a small marginal opinion. A substantial number of Canadians disagree with my proposal and many of them have been extremely frank about my idea and where I can shove it. Parsing the all-caps arguments was tiring, so I decided to personally reach out to them instead. What I found beneath the angry abuse were several legitimate fears.

The most common objection was that refugees harbour terrorists. James Carey from Bathurst, N.B., whom I engaged by Facebook Messenger, considers me a “bleeding-heart libtard” for suggesting we should allow terrorist “scum” into the country. John Groves from Ottawa said on Twitter that “taking all refugees would be a victory for ISIS.” I heard the same thing on a talk radio show in Calgary. It should be no surprise that this would be such a prominent anxiety. Although the numbers demonstrate the actual threat of terrorist attacks is laughably low, the government and the media have made us frightened of our own shadows.

I also heard that our economy simply can’t afford to take so many refugees. According to the Forum Research poll, if you live in Quebec (struggling with a high unemployment rate) or Alberta (reeling from low oil prices) you are the most opposed to new refugees. Similarly, the less educated you are, the less welcoming you are. A related concern was that there is only a finite amount of money in the federal budget, and we should not spend it on foreigners before we’ve looked after our veterans, the homeless, First Nations, and seniors living in poverty.

There is also the worry that Canada’s social fabric would not withstand so many refugees. I had a long conversation about this with Werner Patels from Quebec City. Although he migrated to Canada from Austria 30 years ago, he doesn’t think the current wave of refugees are from “compatible cultures” and they won’t assimilate as he did. When I called Robert Kraychik, he made the same point: Without English or French, Syrian refugees won’t integrate into Canada or accept Canadian values. Interestingly, Kraychik told me he is the son of Jewish refugees from the Soviet Union who had to learn English when they arrived. Carey, my fan from Bathurst, was also concerned about the capacity for assimilation. He wrote me that the refugees “do not speak neither of our official languages and have next to zero skills.”

Kraychik, like many people, pointed out that some Muslim states are taking no refugees. This is true; already brimming with guest workers, the ruling families in the Gulf states are terrified that an influx of Syrians could threaten their grip on power. But other Muslim states, such as Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, are housing more than three million refugees between them. There will always be someone else who could do more, but does that mean we should do less? I’m not convinced.

[widgets_on_pages id=”Election”]

One area where my critics and I agreed is that taking in refugees is not a permanent solution. Indeed, when polled by Forum Research, the most common suggestion for addressing the refugee crisis was to continue bombing ISIS targets, followed by sending humanitarian aid to refugee camps, points raised by both Patels and Kraychik in our conversations. And Matt Radford, who spoke to me from Woodstock Ont., made the suggestion that Canada should train and arm the male refugees to fight ISIS and Assad themselves.

After talking to some of my angriest critics, I confirmed a suspicion. It’s too easy to dismiss opposition as being only due to racism or Islamophobia (although there is plenty of that). Behind the spittle-flecked tirades and name-calling are legitimate fears and reasonable concerns. In all cases, these worries can be addressed. Indeed, before Canada could take any more refugees, they must be.

But the conversations also left me puzzled. Why do people who can be so thoughtful and eloquent in person act like slow-witted children with anger-management disorders online? I’m going to call some of these folks back and ask them.