Why life in Acapulco is far from sunny-side up

David Agren explains how Acapulco’s dysfunctions have become a metaphor for Mexico’s struggles

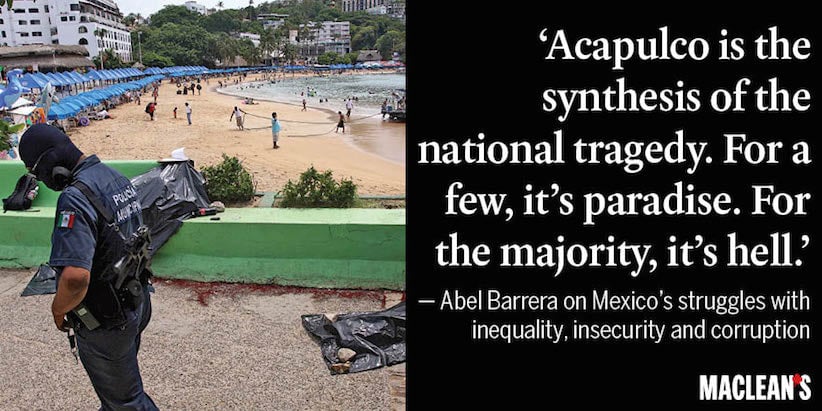

A police officer walks near dead bodies lying on a street facing the beach at the Mexican resort of Acapulco August 16, 2011. Two men were shot dead by unidentified gunmen, according to local media. (Reuters)

Share

The annual Tianguis Turístico trade show was once the social event of the year in Acapulco—“a mini Mardi Gras,” quipped one long-time participant—that seemed to be as much about boozing and schmoozing as business and brokering deals. A showcase of Mexico’s tourism industry dating back to the ’70s, it showed off the best of Acapulco: its picture-perfect bay, beaches with bath-warm water and a nightlife pulsing into the wee hours.

But in 2012, the federal government started moving the exhibition to new locations around the country, apparently a result of Acapulco’s fading appeal to foreigners. Once the granddaddy of Mexican destinations, Acapulco has struggled with security problems and scandalous headlines in recent years—from revelations that 60 bodies were abandoned in a crematorium to schools closing after extortionists demanded part of teachers’ paycheques. A 2012 report (blasted as inaccurate by locals) branded Acapulco the most dangerous city in Mexico—with a homicide rate of 142 killings per 100,000 residents, six times the national number, according to the Citizen Council for Public Safety and Criminal Justice think tank. Troubles in outlying areas have also ruined Acapulco’s reputation. The state of Guerrero, known as El México bronco (the Untamed Mexico), is still roiling from the kidnapping and killing of 43 teacher trainees in September 2013.

Acapulco’s dysfunctions have, for some, become a metaphor for Mexico’s struggles with inequality, insecurity and corruption. The latter was highlighted in 2013, when hurricane Manuel soaked tourist developments and working-class communities that had been built on wetlands 20 years earlier with improperly issued permits. “Acapulco is the synthesis of the national tragedy,” says Abel Barrera, director of the Tlachinollan Mountain Human Rights Center. “For a few, it’s paradise. For the majority, it’s hell.”

Related reading: The brattiest pack in Mexico

Earlier this year, in an attempt to revive the port city, the Tianguis Turístico returned to Acapulco. It was a somewhat staid affair, with more private events sponsored by state tourism commissions and less clubbing and partying than in past years. Still, organizers hailed it as a success and a signal of better times ahead for Acapulco.

There are, after all, some encouraging signs. The homicide rate in Acapulco last year dropped 40 per cent, according to consultancy Lantia Consultores. Long-neglected projects, such as fixing the waterworks, are finally under way. Even the president’s family is vacationing again in Acapulco, while ex-president Felipe Calderón was in town over New Year’s. Mexican tourists stormed the city for the Holy Week holidays, soaking up the sun as soldiers and federal police patrolled the tourist strip in pickups with gun turrets.

“If it were the Acapulco the rest of the world knows, the president wouldn’t come here,” says Erick de Santiago, owner of the Playita Santa Lucia Beach Club—a hangout for the cast of the MTV Latin America show Acapulco Shore—and founder of a campaign, Habla bien de ACA, or, “Speak well of here” (ACA is also short for Acapulco). “This negative situation we’ve been in doesn’t last forever,” de Santiago says.

Still, returning Acapulco to its former glory seems a near-impossible task. Even during the Tianguis Turístico in March, renegade members of a combative teachers’ union, carrying clubs and placards with faces of the 43 murdered students, crashed the event. Rows of riot police impeded their path, just as they did during a pro tennis tournament in February, when teachers tried to close the airport and a riot ensued. Classmates of the missing students and members of the teachers’ union have blockaded the Mexico City-Acapulco highway on long weekends, leaving vacationers stranded for hours at a time.

Related reading: Mexico’s blockbuster of a scandal

Locals express frustration, especially with the spillover of troubles from Guerrero (a day’s drive from Acapulco), where organized crime and the cartels are infiltrating the municipal governments. “What happened in Iguala”—the site of the students’ disappearance, allegedly at the hands of crooked cops, acting in cahoots with a cartel—“was a tragedy, and we get the butt of it,” says Robyn Sydney, an Acapulco resident and well-known environmentalist. “We’ve had such terrible press,” says Ron Lavender, a realtor with 60 years experience in Acapulco, where property prices are running “60 to 80 per cent” of what they were five years ago.

Critics contend Acapulco authored its own collapse through corruption, poor urban planning and bad politics. Mayors have routinely used their offices as springboards to other political positions and pursued short-term projects. “It’s rare that a municipality has had such a long sequence of dismal rulers,” wrote commentator Leonardo Curzio in the newspaper El Universal.

“All products, including touristic ones, have a life cycle,” says former mayor and ex-Guerrero governor Zeferino Torreblanca. “Acapulco has turned into a big city with a beach. What comes with that? All the big-city problems.”

While Acapulco put Mexican tourism on the map, attracting everyone from John Wayne and Johnny Weissmuller to John. F. Kennedy and Bill Clinton (who both honeymooned here), nowadays, the cruise ships seldom call and just two scheduled international flights arrive daily. Some snowbirds from Quebec still winter in Acapulco. One cluster plays pétanque in their trailer park and watches hockey via satellite. “It’s safe,” insists Antoine Compan, a retired autobody-repair worker from Mercier, Que. But convincing other snowbirds to try Acapulco can be a tough sell. “We went to do publicity [in Montreal] and they treated us like crazy people,” says Compan, who organizes RV convoys to Acapulco.

If nothing else, an element of nostalgia still adds to the city’s appeal, especially for Mexicans. “Everyone loves Acapulco because as youngsters, they had their first experiences here,” says Antonio Palazuelos, a local lawyer and member of a prominent Acapulco family. “The first place people got laid, got drunk, got stoned, it was in Acapulco. It’s been going on for three generations.” Long-time residents recall a star-kissed pueblo far from the madness of the 747,000-person metropolis it’s mushroomed into. They also like to name-drop. “In the zócalo [town square], you would see all the movie stars,” Sydney says. She moved to Acapulco in 1967 and ran a dive shop with her husband across from the Hotel Boca Chica—featured in Elvis Presley’s film Fun in Acapulco. She recalls attending a matinee showing of Rosemary’s Baby and sitting a few rows behind Roman Polanski. “I was sitting on the aisle and there walking by was Sharon Tate,” she says.

“If you had a past like ours, you would be living in the past, too,” says Anna Archdale, an ex-model and Palazuelos’s wife. “Unfortunately, she adds, “what happened to Acapulco is it became a city, an ugly city.”

Crime became Acapulco’s calling card, with cartels battling to deal drugs in the city and to smuggle in shipments along Guerrero’s thinly guarded coastline. It was an attractive destination, easy to fit in, and the cops were corruptible. When the Beltrán Leyva cartel was dismantled, smaller groups took over and continued fighting for territories. “There’s total impunity,” Archdale says. “Everyone has a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

Catholic churches in Acapulco fly white peace flags, as the local archdiocese has prioritized providing attention to victims of violence. It’s even training teenagers to intervene in cases of youth at risk of becoming cartel thugs. One priest, Father Jesús Mendoza, started tracking the numbers of victims of kidnapping, disappearances and murders at his parish in the La Laja neighbourhood. “It’s in the hundreds,” he says.

Officials insist that tourist areas—such the Costera, the strip lined with hotels circling the bay—are kept safe. “It’s protected,” says crime reporter Francisco Robles, while watching, not far from the Costera, the federal police inspect an abandoned vehicle suspected of containing the remains of a person whose head was left as a warning in another part of the city.

“Crimes against tourists aren’t common,” says Luis Monroy, principal of a junior high school in the rowdy Ciudad Renacimiento neighbourhood. But residents of rough neighbourhoods high above the bay say police patrols only happen occasionally. “The outskirts of the city are extremely insecure,” Monroy says.

Boosters insist their city’s glory days aren’t gone for good. The federal government is once against promoting it internationally. Talk in town is for more developments to be built south of the city, where the worst of the floods hit (reflecting the old Acapulco ethos of build, build, build). “Acapulco is stuck in the ’70s,” says Archdale, who suggests the city start selling its vintage appeal. “The only way to go here is to go retro.”