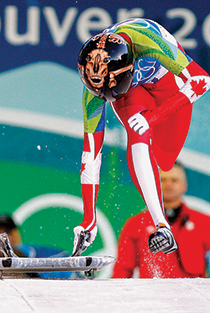

How the rodeo got Olympic sledder Mellisa Hollingsworth back on track

‘I wouldn’t change Whistler,’ Olympian says. ‘I was humanized.’

Roger Lemoyne

Share

There is a woman from Ledbetter, Texas, a horsewoman and barrel racer named Tammy Fischer, who rides tall, in Mellisa Hollingsworth’s estimation. So much so that a conversation about Hollingsworth’s quest to qualify for the Sochi Winter Games and her determination to stand on the podium this February—after her tear-filled fifth-place finish at the Olympic skeleton track in Whistler almost four years ago—has taken a sharp turn into the rodeo arena. Hollingsworth, 33, has a story to tell about her mentor, about loss and pain and lessons learned, but first, a bit of background.

Rodeo is Hollingsworth’s other love. When she isn’t battering herself silly by rocketing headfirst down an icy skeleton chute, her preferred mode of transportation is a horse named Pepi, ridden at top speed around a twisting course of barrels. Hollingsworth hails from Eckville, Alta., and now lives in Airdrie. Horses and rodeo are part of the culture and her family’s life. Her father, Darcy, raises bucking horses. “I’m a competitor. I’m not really the person who enjoys going on a trail ride,” she says. “I can appreciate that, but I want to be in the arena, working on drills with my horse and setting a goal and seeing improvements.”

Every sport has its heroes. In skeleton, one is her cousin Ryan Davenport, a two-time world champion and now a sled-maker. He introduced her to sliding when she was 15. She excelled from the get-go; those hair-trigger sleds being as spirited as Dad’s hell-for leather horses. She was national champion within three months of entering the sport, a bronze medallist at the 2006 Turin Olympics, and has 34 World Cup podium finishes.

In rodeo, Tammy Fischer is one of the great barrel racers of her era, a sport that is positively mainstream compared to the esoteric world of skeleton. Hollingsworth interviewed her at the 2009 Calgary Stampede while working as a rodeo commentator for the CBC. It gave Hollingsworth a front-row seat on what has become an epic piece of Stampede lore. Fischer’s 18-year-old son, Riley, had been killed in a car crash weeks before the Stampede. She buried him and returned to the familiar comfort of the rodeo circuit. A week later, Fischer’s horse flipped end-over-end during a competition. And, days after that, her rig caught fire en route to Calgary. “She is a wreck, a complete wreck,” Hollingsworth says of Fischer. “She gets to Calgary and pretty much is [asking], ‘What am I doing here?’ She wants to crawl up into a ball. Who wouldn’t?” But she raced in an event where, in past years, with her son cheering her on, she had always fallen short of victory. This time, with a banged up horse and a broken heart, she won, tearfully dedicating the win to Riley. “All those runs, all that practice, everything came into place,” says Hollingsworth. “It was just supposed to happen.”

It was an inspiring moment for Hollingsworth then, and one she drew on months later, when things went bad in Whistler at the 2010 Olympics. Hollingsworth was in silver-medal position and launched onto her sled for the final with a personal-best start time. She hit the wall at turn 6, shaving hundredths of a second off her time, and knocking her into fifth place. She was gutted. “I feel like I’ve let my entire country down,” she said in a tearful apology that elicited a response she never expected.

Thousands of Canadians sent letters and emails of support, often sharing their own stories of moving on from disappointment. She looks back on it now as a defining moment in her life. “I wouldn’t change Whistler,” she says. “A medal would have been wonderful, but I don’t think my story would have had the same impact on anybody as not achieving that goal and going through the heartbreak. I was humanized, in a sense, and people were able to connect with me—they have had heartbreak, as well.”

She decided then to try for one last Olympics, but also to reinstate a missing dimension to her life: rodeo. “I needed a little more balance,” she says after years of a singular focus on sledding and the pounding that puts on body, head and mind. She started rodeoing in the summer, coming back later to winter training groups. The results have been mixed. The podium finishes haven’t come as often in recent years. She finished fifth at the world championship last year and sixth in World Cup standings. “Frustration is the only way to describe how I felt this winter,” she wrote in her blog at the end of last season. The battering of training runs and crashes has taken a toll. Last season, she battled illness, chronic headaches and fatigue, possibly due to what sliders call “sled head,” the concussive effects of too many training runs that end too many careers. “Concussions scare me so much, I wonder if it’s worth ‘tobogganing’ anymore,” she wrote.

In part to clear her head and mind, she used several weeks of off-season downtime to accept Fischer’s invitation to ride at her ranch in Ledbetter and learn from the best in Texas rodeo country. So many of the skills transfer from one sport to the other: the adrenalin rush of the start line, finding at top speed the right line and the sense of flow. “I can draw on skeleton to help me through,” she says. “Even though you’re riding a horse, it’s a being. I sometimes say my sled has quite the personality itself.” This summer and fall, though, Pepi and rodeo had to wait for next season; her sleds and Sochi are the focus.

She says she’s put the Whistler disappointment in perspective. It is part of her story; not something to run from, but something to utilize—something to feed her rodeo summers and her winter dreams.