And in the end, the love you take . . . can win you bronze

A bronze medal for Canada, and Sir Paul McCartney singing in the stands

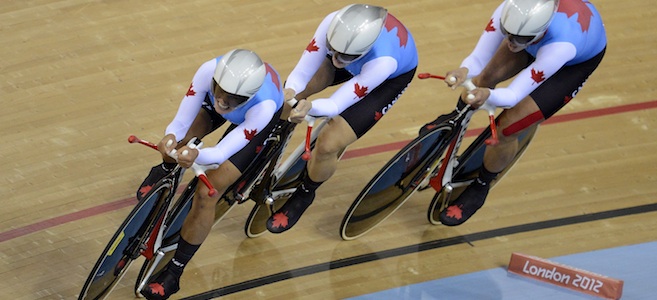

Canada’s Jasmin Glaesser, front to back, Tara Whitten and Gillian Carleton race to bronze in the women’s pursuit at the Olympic Velodrome during the 2012 Summer Olympics in London on Saturday, August 4, 2012. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Share

In the end, it came down to three Canadian women in their skin suits and Buck Rogers helmets trading leads with the Australians and racing the clock, racing for bronze. It came down to the Canadians being on the right side of a 0.181 of a second differential: a twitch, a blink, an eyelash.

Most Canadians have never seen a cycling velodrome, with its 42-degree banked turns so steep you’d drop like a stone if speed wasn’t pasting your bike to the Siberian pine track. Such tracks are a rarity in Canada. Not so in Britain, where cycling is a religion, and where it has delivered a pile of medals for the home team at the London 2012 Olympic Summer Games.

No surprise, then, Saturday night that the Brits took the women’s team pursuit gold here ahead of the Americans. The Canadians—Tara Whitten, Gillian Carleton and Jasmin Glaesser—had raced the British in the first heat Saturday and the roar of the crowd almost lifted the roof off The Pringle, as it’s become known, because it swoops like the potato chip.

You could let the ear-bleed noise be a distraction, Whitten said later, or you could feed off the energy. They kept the energy, thanks, and made it theirs’. “You could just take that and think, they’re cheering for me, they’re cheering for me,” said Carleton. “You’re just thinking there are 10,000 people cheering for me.”

That race lifted them into contention for the bronze, and a race later that night with the Australians that was microscopically close. All it would have taken to lose was one tiny mistake as the riders exchanged leads with their teammates, hanging out too long up the banked track, for instance, before rejoining the slipstream behind their mates.

“We definitely had to focus on the little things that were going to make the difference,” said Carleton. “During the last three laps I was seeing stars, I probably had my eyes closed half the time.”

After God Save the Queen was played, the women stood on the podium with their medals, basking in the sort of adulation Canadian cyclists rarely get at home. Suddenly the strains of Hey Jude played on the sound system, cutting through the noise.

The crowd began to sing, and the velodrome cameras zoomed in on a chap in a white shirt, waving a Union Jack. He was singing, too, having written the song.

It was that sort of night. A bronze medal for Canada, and Sir Paul McCartney in the stands, singing only to them.