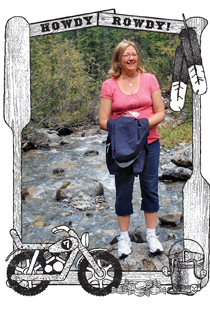

Beatrice Sorensen

Always ready with a hearty laugh, she loved to volunteer. After a rescue at sea by the coast guard, she was quick to sign up

Illustration by Ian Phillips

Share

Beatrice Sorensen was born on Nov. 21, 1960, in Ashcroft, B.C., the nearest place to home with a hospital. She was the youngest of seven sisters, which brought her father Raymond Schultz, a Saskatchewan farm boy turned B.C. logger, as close as he would come to his dream of fielding a full baseball team of girls. They grew up in Clinton, a village with wooden boardwalks and a highway main street where the population never quite hit four digits. Every Sunday their mother Ivy, born on an Ojibwa reserve in Ontario, insisted that washed clothes get fresh air, even in the winter. The troupe of daughters dutifully retrieved laundry hanging frozen stiff. Little Beatrice did what she could, but her tiny hands usually got too cold. She preferred to slide down a nearby hill on a scrap of cardboard or, in the arid summers, explore the hillsides until night fell.

She was a quiet, tentative girl who tiptoed around the limelight. Friends struggled to get her in photographs. Her first boyfriend managed to get her into a canoe, a red-orange slice of fibreglass they would strap to the top of his yellow Ford Pinto. She later moved to Kamloops for college and became an accountant. She married young, divorced, then married Randy Sorensen, with whom she had two children, Sara and Zachary. After a time in Vancouver, they settled in Sechelt, a lush earthy district of a few thousand on the coast, about 30 minutes from the city by ferry.

Something changed with Beatrice around the time her father died in 2007 and after she divorced Sorensen. She volunteered more and blossomed at her job in social services. She eased herself from the margins, outside her comfort zone. “She found her calling, the giving of herself,” says her sister Geraldine. And she got a motorcycle, a green Harley-Davidson. She wore black leather boots, black leather pants, black leather everything. She faced her licence exam with trepidation, on a day pouring heavy West Coast rain. When her boyfriend Terry Friberg asked if she was sure she wanted to take the test that day, Beatrice assured him she did. Two hours later, she announced her return with a rumble. Terry opened the garage. She sat silently on her steaming hog in the driveway, soaked and dripping, beaming her biggest smile.

At work, Beatrice managed money and morale. She greeted co-workers with a “Howdy rowdy” and a laugh, more wa-ha-ha than tee-hee-hee, that could be heard through walls. She wore silver rings—on each finger—and bangles on her wrists. Her office featured a bottomless bowl of butterscotch candies and an open door.

Beatrice joined canoe and dragon boat clubs. She was five foot nine inches and substantial; lily dipping was not her thing. She enjoyed the camaraderie, but mostly she loved being on the water. She said she liked having wind on her face and seeing so far into the horizon, like she could look ahead and go forever. Fellow paddlers called her “giggly worm.” Twice she joined the Pulling Together Canoeing Society on 10- to 12-day canoe trips with aboriginal youth.

During one such trip in July 2011, on a day with menacing clouds and rough waters, the flotilla of canoes and their 250-odd paddlers called for a coast guard rescue. Most scurried aboard a barge. Beatrice and three others opted for a diminutive dinghy. The crew warned it might get a bit wet. Off they went, pummelled by three foot waves. Before too long, Beatrice took her eyes off the frowning sea and glanced at her soaked companions with fast-bruising bums. She cracked a joke and wa-ha-ha-ed. As usual, her humour infected them. For the remainder of the ride, the four women laughed between bracing waves. Six months later, Beatrice joined the Canadian Coast Guard.

She qualified as a search-and-rescue volunteer with a perfect score. She was happiest at the helm, steering her boat with silver-ringed fingers at 55 km/h, blonde hair dancing behind her white helmet.

On Sunday, June 3, she received a call for a training mission. Within 15 minutes, she had geared up and joined three others on an inflatable Zodiac heading toward tidal rapids in Shookumchuck Narrows. High tides made waves and whirlpools fiercer than usual. The boat cleared the thrilling rapids. Beatrice enjoyed herself enough to insist on doing it again. Back they went for a second descent. This time, the boat flipped, and Beatrice and a crew mate drowned underneath. Beatrice was 51.